Hands to fly the land of the farmhouse

- It is evident that the model of traditional farmhouses in the Basque Country has been exhausted and is increasingly limited to the imaginary of folklore. It is estimated that in the last two decades 70% of the houses have been lost, and both baserritarras and experts have warned us that the lack of generational relief is an important problem. Urgent matter to be resolved, before late. The agro-industrial policies promoted by the institutions and the lack of social prestige do not contribute to this change. But there are new farming tools that are bearing fruit: The Treatu project, the local food strategies to revitalize the primary sector, the baserritarras networks… The interviewees have reminded us that there is a lack of knowledge of the subject, but that it is a problem for all citizens and that, therefore, we all have to participate in it: “What food, such agriculture.”

It is common to find dwellings abandoned everywhere, or dwellings away from agriculture and livestock. What's not so common is that the baserritars see their lands cultivated, of course, if they're under 40, women and people who are remote from the peasant stereotype. However, there are, in addition to those who live in the dwelling, those who live there. But they are not enough to maintain the needs of the whole of society, let alone to achieve food sovereignty.

The data show the negative trend of the last decades. In the Northern Basque Country, in the last 30 years, one in three villages has not continued, as determined by the Basque Country Chamber of Agriculture. There are 2,500 farms on the road and there are currently only 4,500 farms throughout Zuberoa, Baja Navarra and Lapurdi. The Agricultural Census of Hego Euskal Herria 2020 has also confirmed the downward trend. The INE estimates in the Spanish State that agricultural holdings are 7.6% less than in 2009, but at the same time the area of each holding has increased by 7.4%. This trend is repeated in the territories of Araba, Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa and Navarra, with fewer but growing farms. Industrial model dominance signal. According to the Eustat 2020 Agricultural Census, there were 12,919 farms in the CAPV in 2020, 21.8% less than in 2009. In contrast, the Cultivated Agricultural Area has grown by 38.4% in the CAPV and 13.3% in Navarra.

The industrial model has also prevailed in livestock farming, with a decrease in the number of holdings of all species, with the exception of goats. The largest decreases occurred in birds (-67.1%) and pigs (-65.3%). On the contrary, the number of livestock heads per holding has increased, except for sheep. It is very significant that between 2009 and 2020 the number of pig heads increases by 4377.3% and that of birds by 186.2%. And on whom do farms depend? In Iparralde, one-third of the cottages are run by people over 50. In Hego Euskal Herria the average age is also high. In the CAPV it is about 57 years and three-quarters of the operators are men.

CAP and agro-industrial revolution

It is not by chance the data mentioned, but the consequence of several factors that have occurred in recent years. For example, the agro-industrial model mentioned above, which has been replaced, inter alia, by the Common European Agricultural Policy (CAP). The CAP began in 1979 to support the primary sector, but the reforms carried out since the 1990s have been criticised, especially for the disappearance of small farms, due to the uneven distribution of subsidies. In fact, the CAP subsidizes by hectare and by head of livestock, giving more to those who have it, which favors the accumulation of land and livestock and encourages agro-industrial production. Clearly, the most sustainable products are those produced on a small scale. Etxaldeko Emakumeak has made clear the “inconsistencies” of the CAP: “At the same time, we cannot promote a model of agro-industrial production and develop a policy against climate change.” According to the Association’s baserritars, the distribution per hectare is “in total contradiction” with the theoretical objectives of the CAP, in fact, aims at generational renewal, rural regeneration, social inclusion and environmental protection based on biodiversity, among others.

European subsidies penalise sustainable models

In addition, the women of Etxalde claim that the CAP masculinizes even more the primary sector and excludes women. The gender gap in agricultural aid is significant: Only 31% of the beneficiaries of the CAP are women and, furthermore, they receive in proportion worse subsidies than men, as incumbent women often have smaller or medium-sized farms and more sustainable models.

Factors that disrupt relief

Mirene Begiristain, an agroecological expert, takes the same view: The CAP punishes sustainable agricultural models and does not put women’s work in value. It stresses the lack of important work to “de-territorialize” the primary sector, such as the democratization of rural care, the equalization of land ownership and the balanced distribution of productive work. Begiristain is a professor and researcher of economics at the UPV and has been investigating closely the decline of the primary sector, among others. He is a member of Biolur and olective EHKs and as a consequence of his work with the agents of the rural movement, the causes of the lack of relief are well identified. It distinguishes three main obstacles: the difficulty of access to the soil, the economic viability of the project and the lack of recognition to the garrisons.

Do we have a decent life in the farmhouse? Besides saying that it is a linked and hard work, what does any citizen of agriculture and livestock know?

People who want to start up in the primary sector have great difficulty finding land suitable for agriculture. According to Begiristain, in recent years soil has been artificialized, the lack of soil and soil concentration is prioritized, following the policies of the CAP. Associated with this is the economic viability of the projects: in case of land rental, payment is not viable. That is, if the property of the land is not inherited, with the agricultural income it is “very difficult and complex” to stay in rent. According to those surveyed by the monitors, the average income of farmers does not reach the minimum of 1.080 euros contained in the social charter “in most cases”. They therefore have difficulty in undertaking the investments required by the primary sector.

In addition to these two obstacles, there is the third, where the work of the baserritars is not sufficiently recognized. Do we have a decent life in the farmhouse? Besides saying that it is a linked and hard work, what does any citizen of agriculture and livestock know? Who wants your son to be a peasant? He says living in the farmhouse does not correspond to the current hegemonic life, because successful life is related to holidays, to individual achievements, etc. Therefore, the possibility of developing life within the household is not recognized. “It is a life with another rhythm, irregular, but it offers other possibilities: you decide and mark the rhythms, you have autonomy that you do not have in other works...”, describes Begiristain. He has also recalled that new life models are emerging from the farmhouse and that they are adapting to current life, improved techniques, improved knowledge of production, more efficient, there are possibilities of having free time of their own, there are substitution services to enjoy holidays... And apart from the rigid family model of the farmhouse, collective land cultivation projects are becoming more frequent.

The new baserritars are preventing old mistakes from being repeated and shaping the sector to have better conditions. In this sense, Begiristain considers it essential to develop and articulate social supports. In other words, beyond the subsidies of public administrations, the baserritars are organised together. “In the absence of greater social support, it is very important to care for and help with each other, and to be part of a group of baserritarras gives you that support.”

Training under the protection of tutors

In the Northern Basque Country, people and agents from rural areas have been integrated for years, with a better result than in the Southern Basque Country. Proof of this is the Treatu project, which started in 2016 on the basis of the RENETA project of the French State, and since then young farmers have had the opportunity to learn and test the trade through Trebatu, under the support of ten public agents and agencies working together. They do it, they train it, they learn skills, they acquire skill or trust, and depending on that experience, they decide whether they want to settle on the farm or not. Kattalin Sainte Marie is a project manager and works with new farmers. Daniel Barbera is a farmer and representative of the Chamber of Agriculture of the Basque Country (EHLG) in Trebatu. Both have told us the benefits of the project on newly planted lands of Ahurti (Lapurdi) of participant Aurélie Sausset in Treitu.

The Trebatu network is interconnected with different ropes, all of which are complementary to each other, in which agricultural associations, trade unions, vocational training groups, local public institutions and representatives of the consumer-related social economy, among others, are represented. Sainte Marie and Barbera affirm that they all met naturally in the project, as they needed each other to respond to two major shortages: on the one hand, the lack of relief and continuity of the farms, and on the other hand, the shortages that young people from the rural world had to settle in the farms. They realized that more and more young people who did not live in rural areas wanted to start farming, but who were facing many difficulties. “When they are installed they have stuck a wall, which motivated us to start the project,” explains Barbera. Mirene Begiristain saw the same gaps he mentioned: lack of land, need for more money because it starts to invest from scratch, need for more technical knowledge, and especially lack of a network.

They find an exit in Trebatu. They work in fixed training areas (after a time students change) and in unique training areas (after a time students can settle in these lands): “Trebagune’s idea is to give someone the opportunity to rehearse their project in real conditions, on a real estate, and within legal control,” says Sainte Marie. Trebatu performs four functions. The first is the function of seminar, referring to physical spaces. The second is a care and follow-up function, in which the young farmer can serve as a support and referent to another “suitable” crop, and will help him to build a support network composed of the population of the area. The third is the incubator function, which will lead you to the legal and fiscal field, that is, during your training you will be allowed to act legally on behalf of Trebatu and receive loans, rather than starting your own company from the very beginning. And the fourth is the coordination function, under the responsibility of Kattalin Sainte Marie, which guides administrative tasks, internal and external communication, and which is in permanent contact with farmers.

“They have all the tools to get started right,” says Sainte Marie. “Our goal is to prevent youth precariousness from the start,” adds Barbera. In 2016, 15 people passed through the training centre, four in training, one in reverse and another ten in or in progress. They both stress that “it is very important” Trebatu’s ability to step back, “because it is time to step back”, before he is still not installed and indebted to his neck. They do not see it as a mistake and consider it important to be offered the possibility of choosing a trade; Treatu is a perfect option to test the trade and way of life of baserritarra because it is “real”.

Aromatic plants as a means of life

Bayonese Aurélie Sausset fulfilled the conditions for participating in Trebatu, with a minimum training in cultivation, a guarantee of a minimum income source for investments, but without land or cultivation network. He therefore tests his project on Ahurti lands in the hands of Lurzaindia, producing fresh edible aromatic plants. A year ago, he started to get his head on the project, and he's been putting his hands on it for almost two months. He confessed that he had a full head, but said he would saturate without the protection of Treitu and Lurzaindia. Her support gives Sausset peace of mind, which gives her the opportunity to “focus on work”, dirty her hands on the ground. In addition, the land in which it works has the particularity that the baserritarra that previously cultivated these lands, already retired, lives next door and is very grateful for their cooperation. Sausset will continue to form there and the garden project will develop. “I would like to adapt production according to the demand of the moment,” he says.

Food strategies are the key

Aurélie Sausset makes sure you will meet the request to decide the production. So is that what drives citizen demand? Or does the supply of peasants condition what we eat? According to Mirene Begiristain, neither one nor the other, we ask and offer crops and food “under digital green capitalism”. That is, the market decides what we eat and what we work, and this is based on the destruction of natural systems, according to the theories of several researchers. It's like imagining an iceberg: what you see is what's distributed to supermarkets, which favours capitalism, and production and consumption are underwater, while the deepest waters drown nature and the environment.

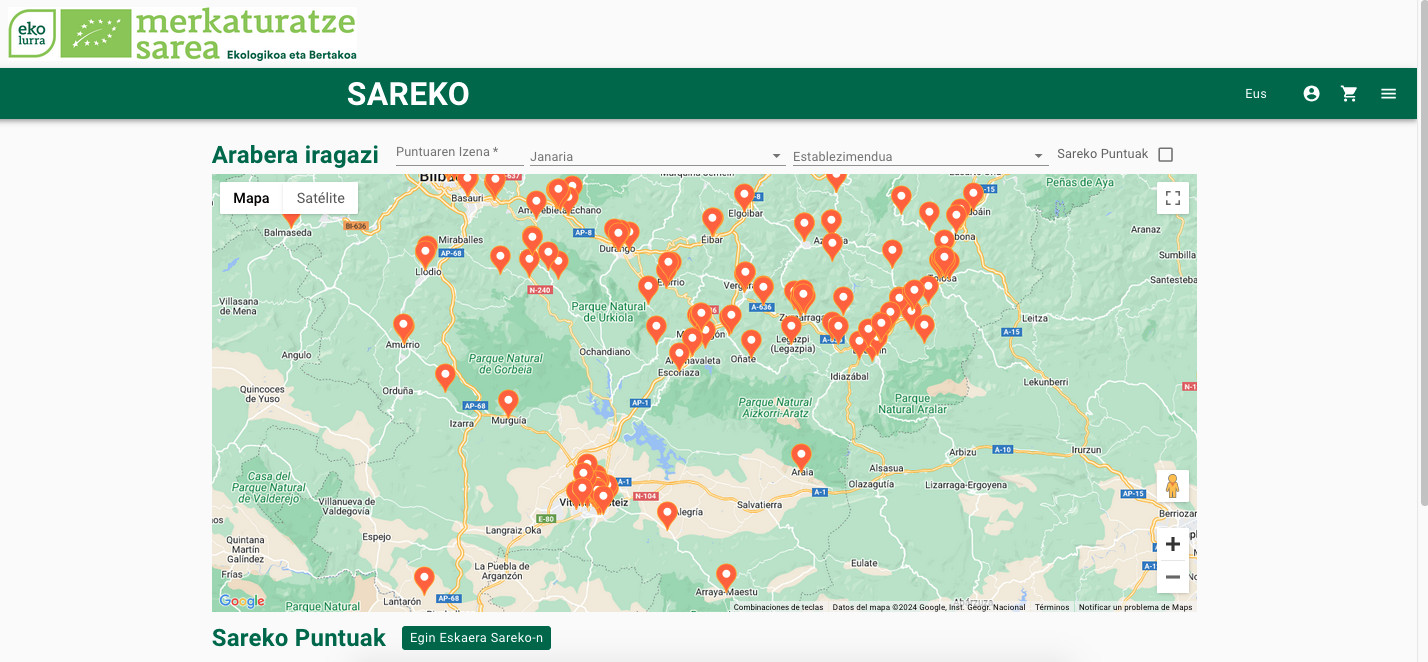

Well, Begiristain says that one of the keys to revitalizing the primary sector is to break that iceberg. According to him, we must create alliances between production (baserritarras) and consumption (citizenship), and change the rest depending on them; it represents distribution or commercialization as “tractor”, something instrumental. He has explained three routes of sale: direct, which requires the relationship between citizens and producers; consumption groups that are being constituted in several localities of the Basque Country; and small shops and consumer cooperatives. It is very clear that this is the way forward, but that it requires the support of public policies.

Develop local food strategies to revitalize the primary sector

It urges organizations to develop local food strategies. “We say: dignified production, popular consumption.” This route has begun to open in some municipalities and from the public administration local food is purchased for educational centers, nursing homes and for preparing meals for public events. In this way, they ensure that food purchased with public money is at least healthy. Not only that, Begiristain also reveals new models, such as the offer of public employment to cultivate the soils of the municipality. The decadence of the dwellings seems unstoppable, but above all because the current way of life has forced it. The question of the primary sector requires going to the roots and posing new challenges. Growers know where to start. “What food, such agriculture.”

Ostegun arratsean abiatu da Lurrama, Bidarteko Estian egin den mahai-inguru batekin. Bertan, Korsika eta Euskal Herriaren bilakaera instituzionala jorratu dute. Besteak beste, Peio Dufau diputatua eta Jean René Etxegarai, Euskal Hirigune Elkargoko lehendakaria, bertan... [+]

The two main voters in Kanbo (the mayor and the prime minister) are the rabid ones. Three citizens have been beaten with a plainta, for protesting in favour of the eviction of the neighbor Marienea.Es the second time that, at 06:00 in the morning, they take us out of bed (with... [+]