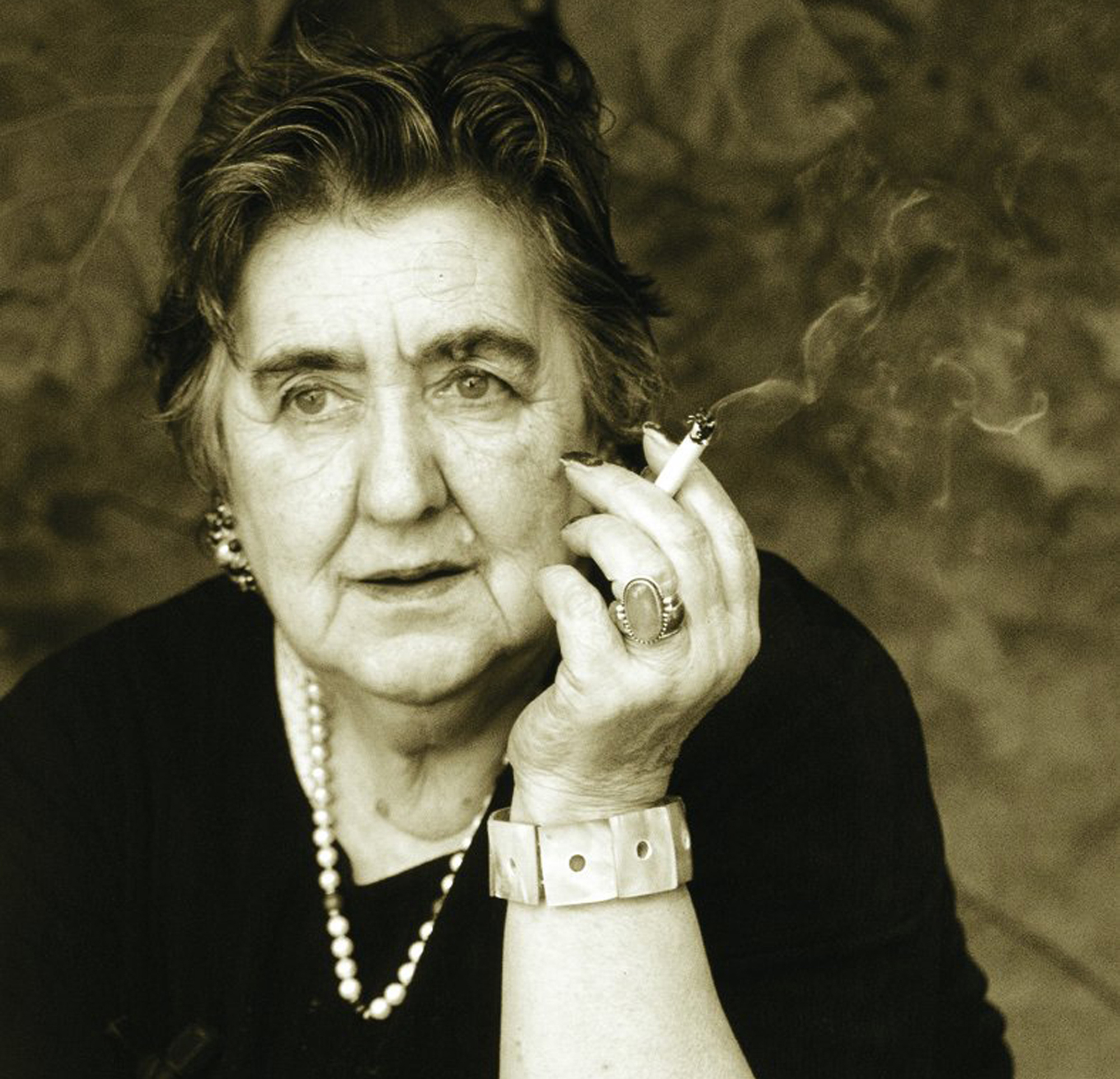

- Alda Merini (Milan, 1931-Milan, 2009) was an Italian poet. He published numerous works, including dozens of poetry books and two or three autobiographies (L'altra verità. Diario di una variety, La pazza de la porta accanto y Reato di vita. Autobiography and poetry).

The editorial Susa has first published in Euskera Merini in the Munduko Poesia Kaierak section. Aiora Enparantza Armentia has carried out a bridge work between Italian and Basque, in which we can read 60 poems. It is an anthology of many works, but unfortunately the library from which they have been extracted is not specified - knowing the Italian versions I have been able to identify several books: La terra santa, La presenza di Orfeo, Destinati a morire, Ballate non pagate...–. On the Susa website we can also read versions in Italian poemon. The translator has done a great job, because the complexity of Merini has brought us with prudence and closeness.

Proof of this complexity is the richness of the worlds it proposes. If you look at the semantic fields, on the one hand, you find words related to the Catholic religion, sometimes in titles like the virgin, the genesis, the holy land, etc. The use of biblical words can reject some readers, but often uses them at a symbolic level. In the poem Tu sei Pietro, which is not in our book, says: Ché cristiana son io ma non ricordo dove y quando finí en il mio cuore tutto quel paganesimo che vivo (“what am Christian, if I do not remember where and when all the paganism that I live in my heart entered”).

We also have poems related to the nature of the poet. Merini tells us what it is to be a poet, what it should be, how he lives in these verses: Poets work at night, singing to poetry, the most beautiful poem, my poetry is as vibrant as fire. I think it is an important pillar of his identity, and he writes it for it: poetry is the identity// essential and unique of life // it moves you // expert puppeteer (page 22). This romantic vision of the poet seems to me to be shared with more writers and I found him parallelism with Gloria Fuerte. The latter says in the poem Sale expensive to be a poet: I start to be food in the shadows/// the hours pass without yawn/// sleep scares me to run away/ - writing to me early. Merini writes: Poets work at night// when time is not in a hurry at them,// by silencing people's noise// and at the end of time lynching (page 21).

As we see, the division of Merini’s work and life is almost impossible. In this anthology we also find words and poems that lead us to manicomias, crazy, electroshock and psychiatric. Very important passages in the author's life were the 20 years spent in the psychiatric ward, divided into different periods. I have read several versions of what happened and it is not easy to avoid a simplistic reading. She married very young and many claim to have a conflictive relationship with her first husband. The man was jealous and also with other women. After a scandal between the two, the man called the ambulance and authorized the transfer of Merini to the psychiatric hospital. Reato di Vita. In her book Autobiography and Poetry, Merini tells this, although she tries to devalue her and justifies her husband’s conduct. In her book Women and Madness, by Phyllis Chesler, she tells very well how most of the women who were in the crazy houses in that century were not crazy. Relatives or husbands were punished for not matching the images and roles of the woman. In fact, involuntary listening was allowed and was common practice. This book contains examples of American writers such as Sylvia Plath or Zelda Fitzgerald, but I wonder if Alda Merini was not a victim of this system either. It was about the extinction of women's intellectual and creative curiosity.

Merini’s work and life is almost impossible to separate: those who have lived in the psychiatric constantly appear in their poems

However, he says he saved the strangers created by his experience. And the ability to look with surprise at what was happening allowed him, besides saving his life, to make clear and brilliant accusations. The dehumanization of therapies was closer to torture than to therapy. In one interview I've read that madness loved it. Sometimes it addresses the issue with metaphors: In the holy land, for example, compare the asylum with Jeri and Palestine. But on other occasions he makes more crude descriptions, such as: down there, where the condemned ones died// waning hell/// in the infinite mental// (…) In the mental// where the bloody ones of the head suffocated/// there you see God//// I do not know, among the madness of your day/ old ideas (page 31). Marking with the lines the descending direction, brings us the voice of those who travel to hell. O: When the sawmills// raised our skirts// and blinked, we made green gestures// at the same time we searched/ stoning (39.orrialdea).

He also writes about love and death. With the pain, the suffering caused by some passages of his life. It is a book with different readings and with a high degree of depth. I particularly liked the poem on page 53, because I think it reflects Merini’s personality. I will not transcribe it, so that you read it in the book, so that you will deal with it letter by letter.

Merini wanted to write it for everyone. It was about people outside the cultural elites reading it and so it happened. He was a well-known, famous and beloved poet in his village and Dario Fo proposed the Nobel Prizes years ago. It was the poet most studied by critics, often leaving behind the books works of many other women like Antonia Pozzi, Amelia Rosselli, Maria Luisa Spaziani or Goliara Sapienza. Many other authors could have chosen from the Italian literary panorama of the twentieth century. Natalia Ginzburg or Adela Turin could be among those who are translated into Basque. And we also have in Basque coming to the 21st century: Susana Tamaro or Elena Ferrante, among others. But I had the feeling that those selected were more unknown and I've come out of secret hiding places. Lorenza Mazzetti, Franca Rame and today Alda Merini. Each faced the century with his own personality and writing. And they've made memory looking inwards without looking backwards.