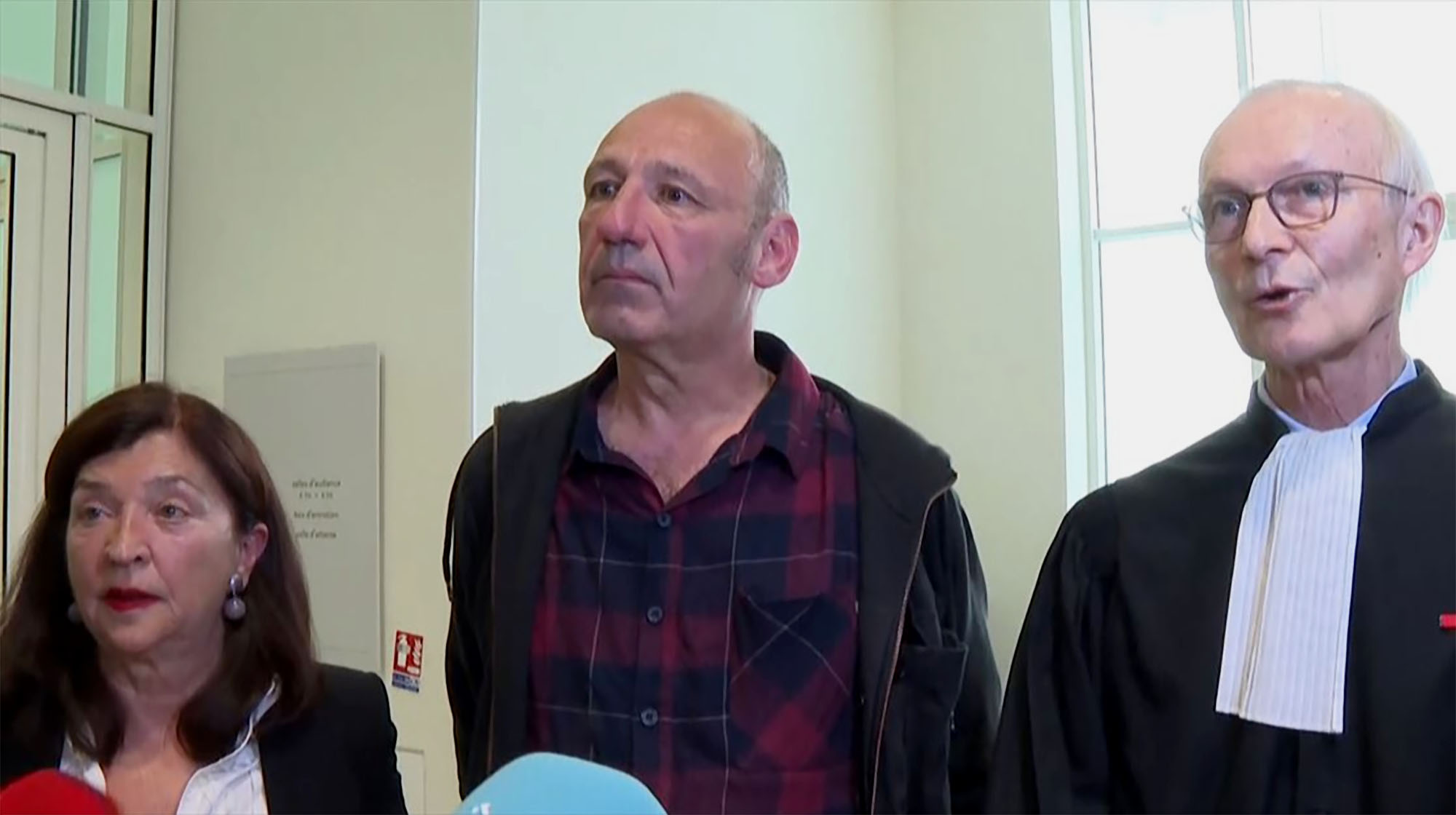

“We give a restrictive sense to politicians, they are the ones dedicated to politics. Txomin Iturbe went further."

- As a young man, ETA's historical boss, Txomin Iturbe, used as a soccer keeper "Aurrera bolie!" When I threw the ball forward. He also left the phrase in handwritten postcards in Algeria shortly before his death in 1986, together with his signature. “This phrase took on another dimension with his death, some of us consider it as our phrase,” says Jokin Urain at age 35. In a way symbol of the symbol. Maybe that's why he's taken the phrase to the title of the book that composed it, so it's postponed along with the character's biography. It complements the biography with the testimonies of those who met Txomin Iturbe, who is also a chronicle of his time.

Why now?

Because until now it has not been possible, especially because Txomin [Iturbe]'s biography was due to what donor testimonies have in their memory, and because these testimonies still had too much effort to tell things, especially because of the judicial consequences that it might have.

He has explained Txomin Iturbe as an example of his generation. What is that generation?

Born at the end of the so-called Spanish Civil War, the first generation dared to take care of what had fallen into despair and face the pride of the dictatorship. This generation shows that dictatorship can be fought against this seemingly all-powerful, it can be confronted.

It talks about the 1960s...

Joxe Manuel Pagoaga Peixoto says the 1960s was a time of planting. Everything that might seem Basque was sown in a society that had been eradicated and crushed from the public and private environment. Then came the new Basque song, where the bases of the unified Basque Country were established, cooperativism was created, the mechanization of agriculture began to take place, and the Basque holidays were also celebrated... There was a teaching of Basque society, a generation that began to imagine another type of Basque Country.

Where did Iturbe get to that movement?

Of the Basque, above all, of the Basque. Its first collision was that of the Basque country. These baserritarras, upon arriving in the street, had their first clash with the Spanish world. On the street they spoke in Spanish, they were called Boronos, Caches. At that time, Lourdes Iriondo also sang “we are young and we disagree”. This disagreeable youth was somehow the one that entered [ETA], because they saw that this institution was facing Franco.

This road led Iturbe into exile in 1968. But it's not a cut in its militancy.

A possible breakdown in the life of any refugee. But there are activists who believed that their armed and social political militancy also had to follow in Iparralde. That is why they moved from the north coast to the interior of Garruze to integrate, work and live in that inner society. Greenhouses were installed, where Eustachian Mendizabal Txikia, Argala, the Txomin himself, met... They wanted to integrate through agriculture, because the world of agriculture was a Basque world in the Northern Basque Country, although it was not nationalist, at least consciously.

On several occasions parapolice groups tried to put an end to it. How did I live?

In 1975 he had his car exploded at the door of the house and he and his son were wounded. Peixoto says he came home half an hour after the attack and Txomin asked him to take him to buy a new car. They bought the car and then he said, “Now let’s go to a pastry shop.” He bought pastries to take them home. “When things are acidic a little bit of hunger does well,” he said something like this. That was Txomin.

He is deported in Algeria. How did he get there?

Txomin was arrested in Iparralde in 1986, he was in prison and from there he was taken to Christmas and Christmas to Algeria. By then there was a rumour of the talks between the Spanish Government and ETA. Soon after arriving there, these relationships began to materialize officially. Txomin met on two occasions with representatives of the Spanish government. But the accident that caused his death soon happened.

When they told it as a car accident. But it didn't, didn't it?

No. When he arrived in Txomin, there were other Basque refugees in Algeria, but through relations between the Algerian government and the institution, clandestinely. But officially, Txomin was the only one. The Algerians gave a convent to the Basque refugees to live there. During the refurbishment work of this convent, while painting the windows of the chapel, Txomin fell down the scaffold and died there. Then, the Algerian secret services and ETA agreed that they would explain death as a car accident. So they wanted to cover in some way that there were more refugees there. ETA was also interested, of course.

Death further reinforced the figure of Txomin Iturbe. He said that he was more than a politician.

We give a certain restrictive sense to the politicians, they are the ones who are engaged in politics. Txomin went beyond, from the political that reached the human realm, to the realm of feelings. Among militants, acquaintances and many Basque politicians, he also had his appreciation, referentiality, his condition of leader; he won because of his way of being, because of his attitude in relations. I knew how to look for common points and not differences.

What is the balance between telling history and falling into personalisms?

We have an attitude opposed to personalisms and I think it is good, because it is also ugly to fall into the worship of some people. But every collective is made up of people, and every person has their own personality, they have their tiredness, their joys, and with all those things of each one the collective is completed. The collection of these individual chips does not take anything away from the community.

To dismantle the prison, write

“I am Jokin Urain, a native of the Alkorta farmhouse, between Lastur and Mendaro. I wanted to live from that rural world, but our political and social concerns led me to escape to the North and from the North to jail. In the years of prison, I have tried to write, especially to dismantle the prison. On that road, I've made some books. I've always tried to write things about jails and prisoners and family members. And as I've been given the opportunity to say goodbye, I've followed that path: The Book of Dreams, The Mother's House, and now this. It seemed to me that it was worth making an effort to make a biography of what in our time was a referent and a natural leader.”