"Etxepare's poem, which surprises me the most, is "Emazen favore."

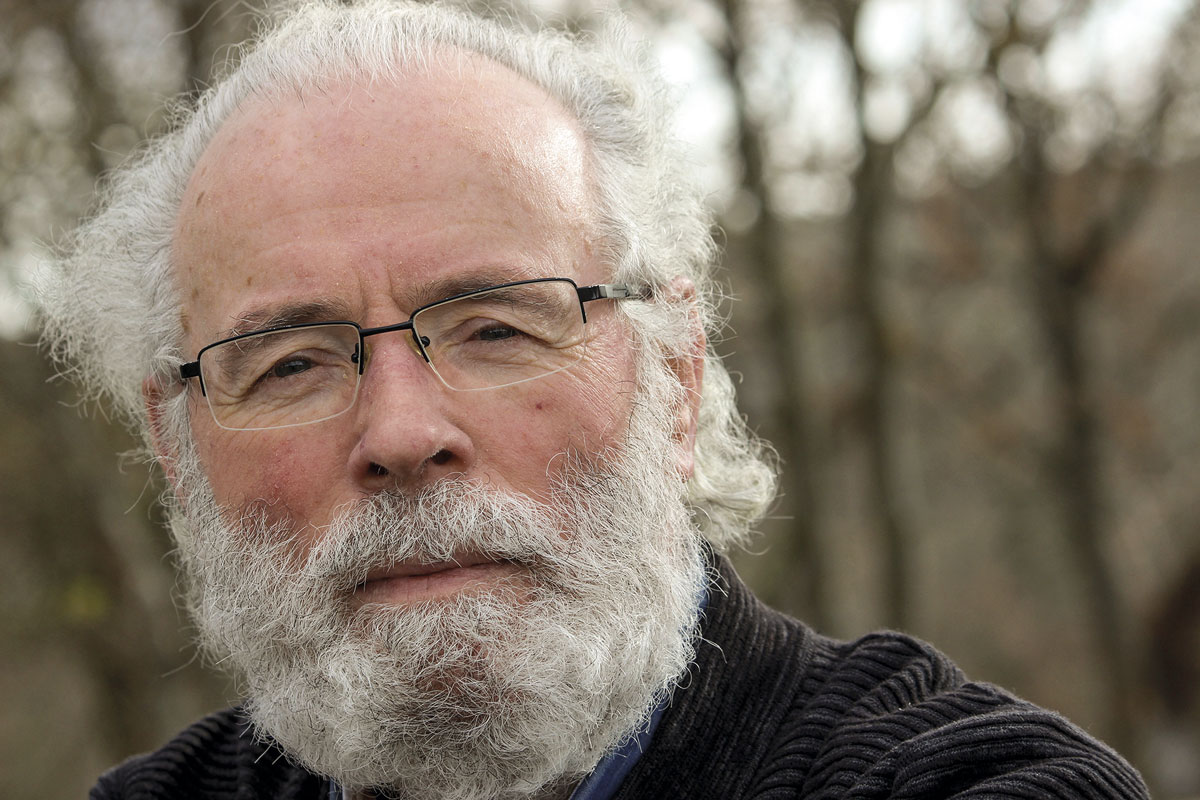

- It's not about standing still. In 2018, she published a girl in an impossible place. This year he published the novel of Venus Una Isla at the entrance of the summer, while in autumn the Basque was added. Bernat Etxepare. Meanwhile, he has also sung Coplas with Agus Barandiaran in the Korrontzi group, the Apaiz prison is in the cinemas and is weekly in Euskadi Irratia. In all of them, Xabier Amuriza.

Bertsolari txapelduna bezain idazle, ikertzaile, saiakeragile, itzultzaile... Hainbat liburu ditu argitaratuak, nahiz gizartearen begietara Amuriza bertsolaria nagusitu zaion beste ezein figurari. Hamaika lan eta eleberri publikaturik ere —Menditik mundura, Hil ala bizi, Oromenderrieta, 4x4 operazioa, Neska bat leku inposiblean...—, aurtengo Uharte bat Venusen ei du bere lanik inportanteenetakoa, has eta buru asmazioa baitu zeharo. Amurizaren barrunbeetara heltzeko bidea dukegu liburu horretan irakurleok. Hobeko dugu esku batean hura hartu, eta, bestean, berriz, euskarazko lehen liburuaren bertsio gaurkotua: Etxepareren poemategia.

The continuous reading of the Classics of the Euskaltegi Bilbo Zaharra is the one that appears behind your Etxepare, a sum of jalgi hadi (Erroteta, 2021)…

I have always had a friendly and close relationship with this Euskaltegi, and when I was informed that they wanted to read Etxepare — and that before three conferences were going to be held, and that one of them was the one I wanted to do — I was happy with the offer. Then, it wasn't the conference that happened, but the essay came out, because I liked the topic. And within the essay, I also adapted an anthology of Etxepare, choosing from each poem four or five presumably more significant stanzas. In the end they were fourteen songs, and adding an explanation, I created a material to complete an act of hour and fourth, declamated and sung. I thought this was how I could offer the listener a fairly clear and comprehensive view of Etxepare.

You have published Etxepare’s book of poems in the unified book, but not the essay you mentioned to us…

I don't know if I'm going to publish it in book format. I'm sure I'm going to put it on the net. But it's done, yes, including that anthology that I've said, because ultimately, Etxepare is singing. It moves within a tradition, without inventing traditions. First, the book Linguae Vasconum Primitiae contains the cooblakari Etxepare. Etxepare was bertsolari in the terminology of Hego Euskal Herria. I completed the anthology, as I did before with Xalbador and Lazkao Txiki. On the other hand, he had a model, because Yon Etxaide brought the verses of Etxahun Barkoxe to the Gipuzkoan. There was therefore a precedent. Thus, when I made a lecture in the reading of the classics, I brought the summaries of the poems of Etxepare and sang in public to students and other listeners of the Basque Country.

And did all of this just do for that one-off occasion?

I did it for that occasion, but anywhere else I would do it at ease. For me it would be a joy, and for listeners I would also say yes. At least for those interested in the figure and content of Etxepare.

Then he translated the whole version of Etxepare.

Yes. I only prepared that anthology, but, misunderstood, they began to say that Amuriza had brought the sum Etxepare, and I began to receive calls on one side and on the other, to see where that work could be found. So, I turned on the light and saw it was worth it. When Euskaltzaindia had translated Etxepare's work into several languages, I thought: “And why not bring the sum?”

.jpg)

"Now and here the only thing I'm going to tell you is that with our verb you can't make a competitive language. It is impossible and it is also impossible”

But how do you bring the sum to Etxepare 500 years ago?

Saying what Etxepare says. That is clear. Whoever reads my version has to read Etxepare, not me. That was my goal. I could harden the rhyme more and the others, but I would lose Etxepare's air. I have made changes, but I have always maintained the content. Sometimes there are also changes of a certain entity, especially when changing the rhymes. Thus, great difficulties arise in keeping the content faithful. Although it is not possible in a hundred per cent, I believe that I have achieved it in almost a whole percentage. I believe that my version has all the air and style of Etxepare, and that today’s reader will easily understand it.

What do these changes of a certain entity consist of?

I've changed the lexicon, I've changed the verb as well, and above all, I've tried to improve a little bit technically. To make a simple translation – I mean the Basque is a sum – I was not going to have those stimuli or interests. I say that technically I have improved, but I have not exaggerated. My main feeling was to bring Etxepare’s text to this day, faithfully maintaining his style. Technically, its rhyme is very elementary and, above all, unvaried. By improving these areas a little bit, I've adapted it to make the language understandable.

He has had to warn of the prayer that Etxepare offers to the virgin within the doctrine.

Yes. Oracionia. In this case, I left the rhyme when I was. Fifteen stanzas in the same rhyme. I don't know if I would have done it for anything. I do not see the suggested intention anywhere. But for once I decided to leave all the poem in the same rhyme. I think Etxepare didn't try to develop the rhyme system. It was in tradition, and at that time, and also later, rhyme wasn't very varied. Except for Oihenart. Because Oihenart was cultured people. Conscious and rigorous. And something sophisticated as well. Etxepare belonged to another tradition that had not given particular importance to rhyme. I didn't have that knowledge. In the surrounding languages, rhyme was much more developed. In Euskera, one of the main reasons for this delay may be the added decline. Very later, Etxahun Barkoxe himself also looks like Etxepare in the rhyme. In the above-mentioned attempt, I explain these issues.

Despite the imperfections and voids of Etxepare, we have Etxepare on the altar…

And that's where we have to stand! Because it's the first one. And the first one is that: the first one, forever. In addition, Etxepare has a clear awareness of being the first. What strikes me the most is that he says with optimism and euphoria that he is the first. In this sense, Contrapas and Sautrela do not believe. It also places the Basque over French and Spanish. Not on par, but on top! “Now he will rise [euskera] / above all...” he wrote. In the cases of Spanish and French, it is not known who was the first writer. They're the deductions of historians. Etxepare clearly states that he is the first Basque writer. How did you know that in San Millán or anywhere else there was no one who had written a book in Basque?

The book consists of fifteen poems. The first, long, religious.

But even though the subject is religious, it's lovely how Etxepare sings these themes. I, for example, am fascinated by the General Judgment. It emits a horror film. I mean, how you build the poem, it's amazing. It's graceful and enjoyable to recite and declaim some of these verses. Today, that poem has no force at all, and it's possible. But many of the machines that we see today are made up of this form of horror film. I've been drawn and I'm interested in that poem. We know what the priest's work was, which was the fear of Christians, and that's what Etxepare did in that poem, and that's what horror films do now.

Then eleven, of love. The thirteenth is autobiographical. The last two, written in Basque.

In the face of love poems, Etxepare sings love in many ways. There we have the desire and the impossibility of love, the game of love, the improbable love… However, above all, the poem that has surprised me the most is Emtzen favore, which I have translated in favor of women. & '97; I found them round, resounding. “Where there are no women / I have no place / man, house / nothing clean. - Everything there is at home / poorly organized / I wouldn’t want it to come close / if there were no women”. This description is also funny. And then: “I haven’t heard my wife / first man attack / yes men to my woman / always first. & '97; Because it creates an evil / always of men. / How is guilt attributed to wives?” And later: “There are a thousand bad men / for a woman / There are a thousand women of a man in his faith”. And the last example. “I don’t dance the woman / raped the man / man yes the man that gives to the lady / zoroki”. I am not able to compare in French and Spanish if there are texts of this kind, no. It may be, but I am surprised that a priest inside the Church, 500 years ago, was so strong in favor of women and against men.

How is it possible for a priest to sing like this to love?

He worked as a lover of the song Etxepare. But also take idealism away from that feeling. However, this rage against men is terrible. On the other hand, confession was already a confession, and from there it was also going to receive information, since in sins the issue of sex was central. Etxepare would surely bring this avalanche against men out of the female confessions, out of the experience of him and out of prison. I don't know where, but he pulled it out of somewhere. As the prison has already been mentioned, it will have to be said that, just in case, Etxepare was imprisoned and also produced an extensive poem on that period.

This is the ‘Canto de Mosen Bernat Etxepare’...

It's a poem that shows a lot of pain. It doesn't tell you exactly what took him to jail, but some collusion. He doesn't say it clear, but he does say that he suffered a harsh prison. The same year that Etxepare published the book, in 1545, the Council of Trento began. Etxepare's work therefore gathers the environment prior to the council. It's their reflection and mirror. Trento, recalling, emerged against Protestantism and led to the creation of seminars. Textually, it arises against the release of creed and to regulate and tighten discipline.

‘May the people of Garazi be blessed…’, the Basque also sang.

I am amazed at the euphoria it imposes on Euskera. If I really felt what he says in those songs, and it seems that yes, Etxepare has been the happiest Basque. And I, the second happiest, because I've done this work. The joy Etxepare felt was great! And you'll ask me, "Today, that optimism, what?" I don't know. The Basque Country Batua has spent half a century since its birth, and we are fighting and working there, not knowing whether we are in resistance or in progress.

Who has this Etxepare done for?

First of all, to anyone interested in the writer. I believe that any Basque suit is interested in what our first writer says and how he says. Form and content. On the day of the show, at Plaza Nueva in Bilbao, I met the playwright Mikel Martínez, and when I explained what I was going to do: “Look, I’m going to read it. Let’s see if we ever know what Etxepare says!” This book is for them. I think having Etxepare in an affordable, understandable way is a good thing. In Euskaltegis, for example, it is worth reading. But who do you have to give only the original? In this book, the two are on par: the original on the left, my version on the right. It can also be a game to make comparisons.

Without explanations, the philologists and many students would not understand Etxepare's work...

To understand the original, many explanations have to be given to the ordinary reader. You will easily understand this translation version. By pure culture, it is up to us to know what the authors of our first writers were. To me, bringing this first book to today's day has given me great pleasure, and that's what I've wanted to do. Who hasn't heard Etxepare? And yet, how many of you know what he said? Well, now he has no excuses to know.

How would bertsolari Amuriza say the following Etxepare says?

Some things, I'm sure, worse. In Etxepare’s book there are many elegant passages, according to the tradition of cooblation, without many abstract metaphors or poetic images, but with naturalness and elegance, despite technical issues. If it had been a subject of mine, I would use metaphors, abstractions or whatever, and other measures and rhymes. But the theme and the goal was Etxepare himself, and for me it's been a joy, a game, a fun.

An island unlike the Venus novel. He hasn't been a game...

Yes and no. I really enjoyed writing that novel. And the truth is, what I'm really interested in is that book. An island on Venus. It can be my most important job. That's where I left my intellectual feeling. A more advanced civilization, a clever humanity. And as a part and exponent of that humanity, I have placed language in a more advanced and intelligent phase.

A smarter humanity, for what? Another utopia?

But a smart utopia. And in this case, not so much utopia, which has served me. It's been a long time since I decided to live intelligently and I've done it. Society is not going to be like the one in that novel, but I can be. In this real society, I can live intelligently.

He has told us that it is his most important work. Why is it so important?

On the one hand, because that narrative is a total fiction. In all the others, I was talking about life. That novel is my whole invention. That's why it's an island on Venus. Those in this society do not understand that world, neither here nor anywhere. That's why I needed it on Venus. Many times I think what it would be, all of a sudden, if we were left with just one human group, without others and without any kind of progress. In this port the narration begins, after a great conflict. And this little humanity manages to survive and create a civilization. An intelligent civilization. At one point, that civilization comes, coincidentally, a very advanced flagship of the advanced world, and that is where the chain of collisions or progressive contrasts begins, which find a much more advanced and much simpler society. They also find a much simpler and more effective language.

.jpg)

"Whoever reads my version has to read Etxepare, not me. That was my goal. I could harden the rhyme more and the others, but I would lose the air of Etxepare."

It says a simpler society, and the Basque society as well. How do you do this?

To know that you have to read the novel! In the case of language, a model is constructed in which, for example, the verb is simplified almost to the extreme. The subject would be long and I do not want anyone to misunderstand me. So now and here the only thing I'm going to tell you is that with our verb you can't make a competitive language. It is impossible and it is also impossible. Consider, for example, the auxiliary way verb il a del inglés he has, from Spanish he has or she has and from French il a. Well, for each of these forms, you need 200 different forms in Basque! Just like entering your house, instead of a key, you have to handle 200 different keys. That's our verb. It can be used to write, as you can do the time and correction you want. But language is basically language, and to speak, if you don't develop a simpler verb, you won't get fluent and socialized language. No, at least, as long as we have to compete with another or other languages around us, and within us!

Complete, competitive, national. In the second book of births of the unified Basque Country there was a section on this: Heroic fantasy of the verb.

Something like that. But to develop this idea, we would need a lot of time to talk calmly to listeners. So, in short, there is a risk of misexplaining it and understanding what I would not like. The civilization of the novel of Venus, an island, doesn't understand why we use the devil verb of it, which is absolutely archaic for them. In your verb you can say everything, clearer, shorter and in a very simplified way. It is not, of course, a transformation from morning to night, but a future direction. Either you simplify the verb or you can't compete. On Venus, its inhabitants talk like this. To the readers who have mentioned something to me, and not much, the truth, I asked first of all: “Have you understood it easily?” and answer: “Yes, yes! Very easy.” And the second question, the immediate question: “In the ease of difficulty, what do you think?” and the answer also immediate: “Much easier.” Well, for me there are no more convincing arguments than those two answers.

Questionable, what you are saying.

Debatable, but inevitable. The sting should be introduced into the central knots, not into anecdotal and strange issues. Those who know have to do what they know, as you know. But if in the future, in the future, the dominance of the Basque country is not made easier for those who wish, it will be difficult to maintain competition. When I say “difficult”, you know what to understand…

* * * * * * * * * * *

Versions

“I wanted to say what Etxepare himself says. On many occasions I have had to change the form of what he says, and I know that, by changing the form, the content is also touched, but I have kept as much as possible what Etxepare meant. What he said may be stronger, or at least more authentic, as he said, but I think to today's reader, 500 years later, my version will be fine. What I have done is not, of course, what I would write, nor all the way I would write. My main concern has been to keep Etxepare. So on the left is the original, and on the right is the version. The reader must compare and judge the work.”

Recital

“In addition to bringing the Basque to the union, I have made an anthology of the poems of Etxepare, and I am willing to recite them, declamarate them and sing them, offering a recital of songs of hour and quarter. If someone asked me, I would love to. Now my goal is not the means of life, but that never comes wrong, because the means of life includes pleasure and pleasure. And it has been a pleasure for me to bring the Basque to Etxepare.”

LAST WORD

Etxepare koblakari

“In the song Contrapas, ‘Heuscara, jalgi hadi campora,’ he says in the first chorus. Then, ‘jalgi hadi plazara’. In the third, ‘jalgi hadi mundura’. But the world seems not to be enough, and in the fourth, it says ‘jalgi hadi mundu guzira’. But he gets more strophes and he doesn't know where to go from all over the world! I knew I had to end the ‘jalgi hadi dançara’, but what fate would I give to those intermediate stanzas? And so, as a slogan of three stanzas, we repeated three times ‘Heuscara’, and there it was. I'm sure that's what happened to him, because I've also seen myself tremendously many times. Etxepare has Koblakari’s mindset.”

I was going to write a column tirelessly, but I found it ridiculous to pretend that at the age of 19 it's collapsed: rendered, tired, disappointed, as if this world had denied me. I found it even more ridiculous to dream of the little little rolls that we have left, to lose me in... [+]

PELLOKERIAK

Ruben Ruiz

Illustrations: Joseba Beramendi, exprai.

Elkar, 2022

-----------------------------------------------

Rubén Ruiz offers a new work of short stories. They are not micronarratives, because the stories, although they can be read independently, have a... [+]

Memet

Noemie Marsily and Isabella

Cieli For Centos, 2022

--------------------------------------------------

We opened the zipper of the camping in red and looked through the leek along with Lucy. With this cover, the reader receives the comic book Memet. Simple words... [+]

Beware of that view of the South. Firstly, to demystify the blind admiration of the green land, the white houses and the red tiles, unconditional love, fetishism associated with speech and the supposed lifestyle. It leaves, as Ruper Ordorika has often heard, a tourist idea... [+]

A Heart Museum

Leire Vargas

Elkar, 2024

-----------------------------------------------------

The Basque cultural system has a thirst for young people. That's what Leire Vargas said in the written column in Berria. The industry is looking for fresh, varied and diverse... [+]

A few days ago, the new French Interior Minister, Bruno Retailleau, joined the so-called "migratory confusion", one of the most pressing issues. It has provided the prefects of the State with clear mandates: zero tolerance towards immigrants and structures and prisoners who show... [+]

.jpeg)