Are there new readers of old books in Basque?

- The literary tradition in Basque is generally broken and unknown. What has been written in recent decades seems, however, to have achieved some stability. However, one important element is missing: to make available the literature of the period prior to stabilization. This would be a twofold task: the reissue of books and the revision of their language.

& '97; Old and

new days,

today we torment you tomorrow,

when

there are silver

people who have crumbled through

the flower

chain.

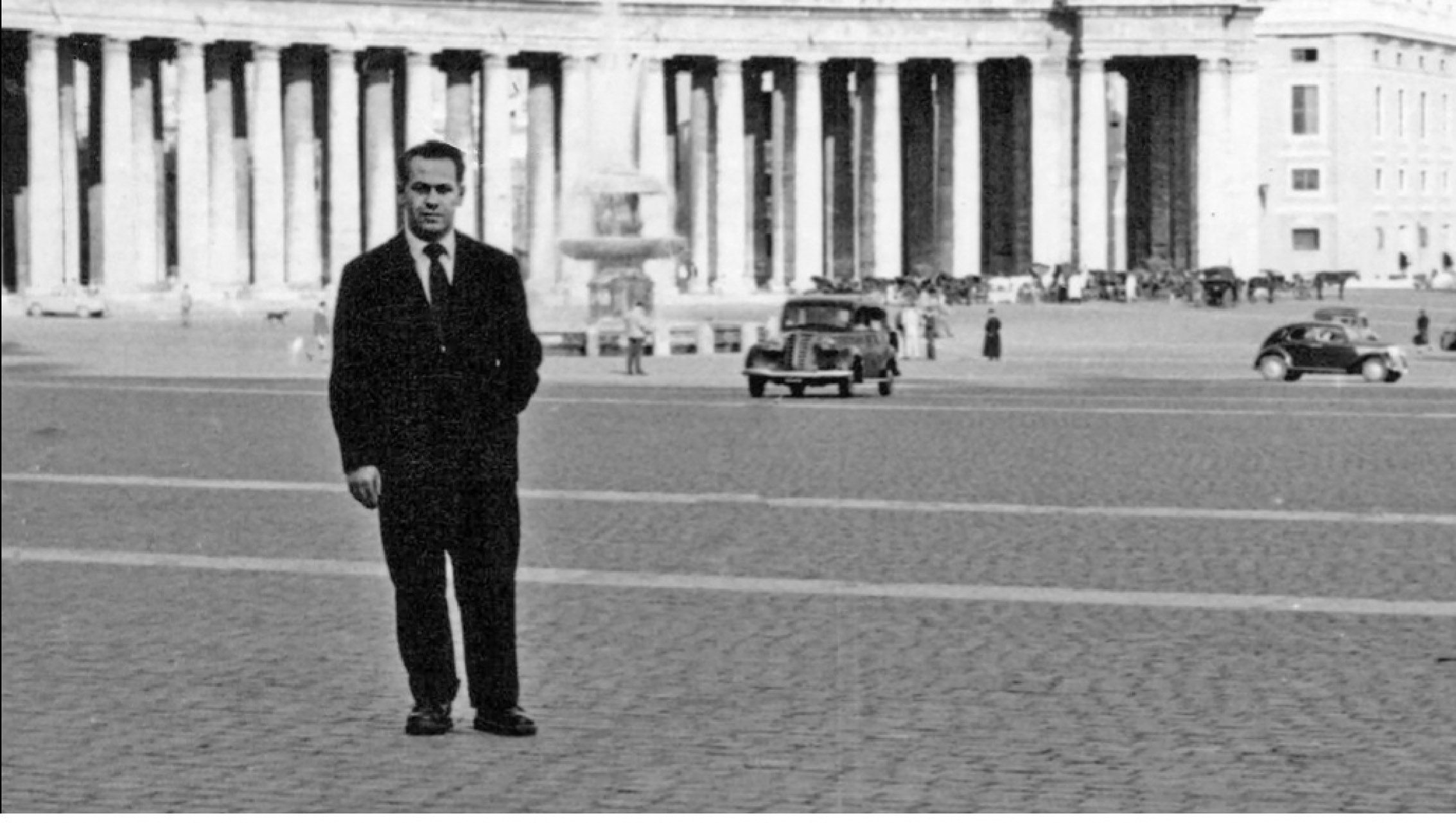

Almost the entire century has been accomplished with the publication of the book of the poet Xabier Lizardi (Zarautz, 1896 – Tolosa, 1933), but since they were published, it is not possible to write today, how does this computer put tileta to “r”? Wouldn't it give you problems when it comes to printing? Decades have not passed in vain, there is nothing more than looking at the evolution of the Basque graphic.

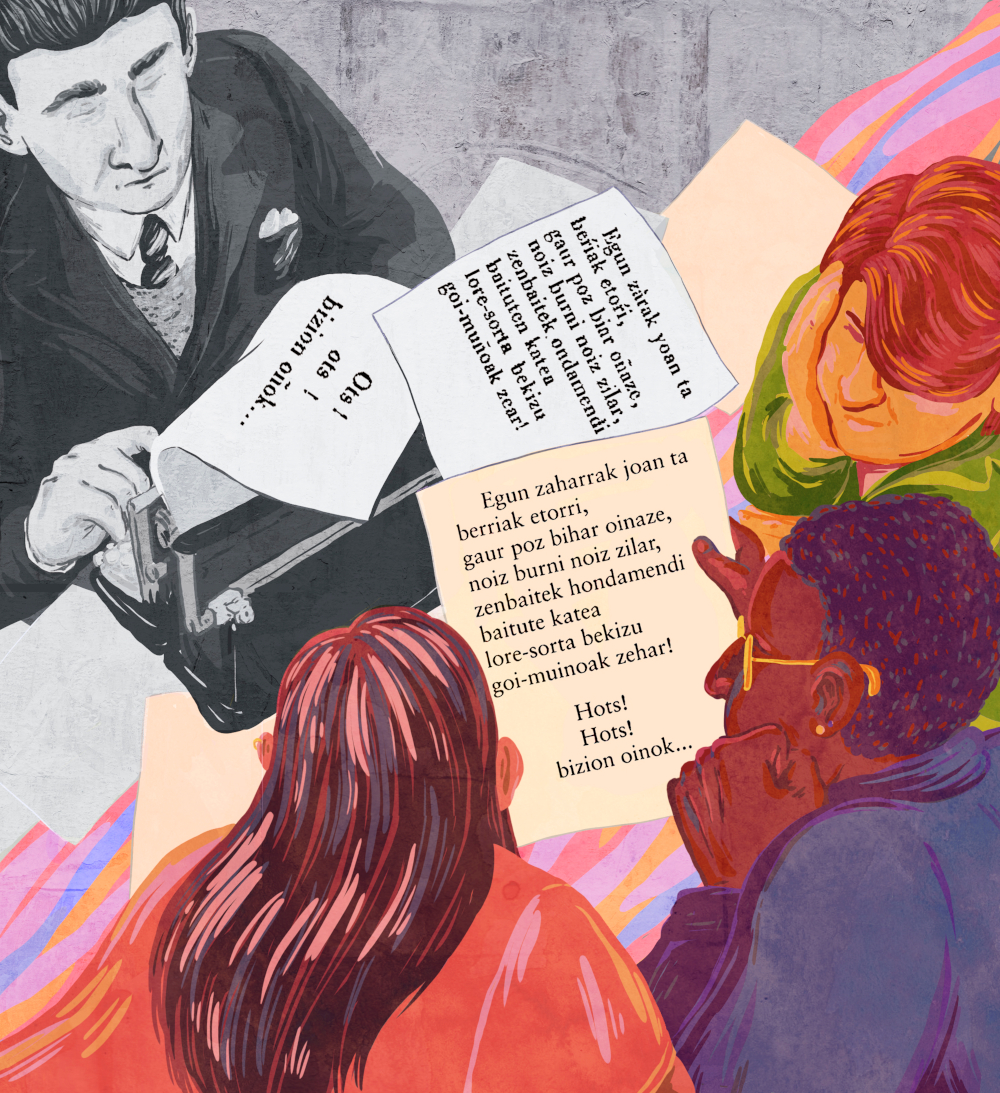

Susa republished last year in Lizardi's Heart Eyes the standardized spelling. In addition to this update, the book includes the artistic intervention of Zuhar Iruretagoiena, which popularizes the artistic pages, and the prologue of Anjel Lertxundi. The reissue of this classic gives the perfect excuse to address a topic that should be of concern to the literary world: Do old books have new readers? Are the most significant works of the literary tradition in Basque available? Both books in hand and texts in hand, since many of them were published, writing in Basque has changed considerably. More than modifying, adding, standardizing. Koldo Izagirre says: “Then writing was a mountain, today we have a plain.” But the question is how to enrich our plain on those then mountains.

In the eyes of the heart in

the hands It is an important book In the eyes of the heart, in that there is no doubt. It is important, as Lertxundi says in his introduction, for its influence on poetic activity, for its simplicity of analysis in the context in which it emerged. It brings together eighteen poems written by Lizardi between 1919 and 1931, it shows a modern and lyrical poetry that breaks with what was then written in Basque. Gabriel Aresti said, “I think Lizardi wrote a golden sheet in the Basque literature, the nicest, the brightest. His name is at the forefront of the world.”

And despite all this, in recent years the book has been discontinued and it has not been easy to get physical copies until Susa has republished the book. This is what Lertxundi says in his foreword: “Today’s readers have not had the opportunity to read in the Eyes of the Heart of Lizardi, they have not renewed, adapted, careful edition. Unified Basque. In a collection and catalogue dealing with literary publishing. Today's poem in the noble company of books and narratives. In an accessible popular edition that takes into account the current conventional reader.”

Today's readers have not had the opportunity to read in the Eyes of the Heart of Lizardi; they have not renewed, adapted, caring for the edition

Why has that been the case? From Lertxundi they launch several questions: “The reason is negligence? Lack of information? A little respect for cultured culture? The fame of the writer he has of Lizardi? Lack of interest, neglect, ignorance? Short-sighted projection of cultural agents in the programming of books to be published? There will be something about it.” The result of all this is that the renewed, adapted and carefully edited edition of a reference work has not come to the hands of the new readers until the City of Zarautz has put money to pay tribute to the 125th anniversary of the poet. In fact, it has not been a simple task to complete that renewed, adapted and careful edition. Josu Landa has done Lizardi's upgrade work by correcting the poet's spelling and explaining the most characteristic synthetic verbs he manages. The Susa edition includes a facsimile of the original to easily compare both versions. The most striking thing is spelling, the one that most bothers reading. It is understood regardless of the consistency and the lexical selection of Lizardi.

Each year it comes in

the literature books, the Basque literature leaves a good harvest, you only have to review the lists after the completion of the Durango Fair. Lots of books every year. In 2020, for example, 30 novels not previously published and almost as many poems, according to the count made by Juan Luis Zabala in the Basque Literature Bookshelf. Among them, some have been much more read than others, others have given much to talk about, but almost two years later the impact is becoming weaker, while others seem to go unnoticed.

Some of these books will leave a mark, they will have a small print run and they will have to be reprinted, perhaps translated into other languages or adapted to a film. The thing is, some books are going to last, they're going to have new lives, and others are not. Because it is not easy to cope with the passage of time, and above all with the arrival of new books, books last little in shop windows, shops and the press. More and more books are being published, less and less breathing.

Let's go back a few years. Books are easy to find if they are not determined, such as those bought and bought each year at the Durango Fair in the same edition. Let's go even further back, when you could read all the Basque books that were published each year. So there were also fewer readers, of course, but that's another thing. If we do so even further behind us, we are faced with a milestone with diffuse borders: the standardization of the Basque Country, of the Basque Country batua.

In 1964, in Baiona, first in the meeting

promoted by Txillardegi and later in the Arantzazu Assembly of 1968, the process of standardization of the Basque Country was launched. On the right track, but not easily, some decisions were made, and above all the choice of several editors and writers widened the place that the Basque batua needed in writing. However, standardization is a process that has not been rapidly stabilized. The proliferation of ikastolas and the institutionalization of the Basque Country after the death of Franco, the creation of the UPV/EHU, ETB, etc., also contributed to this. In the literature, it has not been an easy road until the hour referred to by Izagirre, the generalization of writing and correction according to the rules of the unified Basque Country in the publications has been prolonged for many years as Euskaltzaindia has given rules and instructions and writers and editors have used them.

If we look at the published literature throughout this time, and despite the extraordinary whims, we see this evolution of written language. It can be said that the issue has stabilized in the last thirty years, coinciding with a certain stabilization of the modern literary system in Basque. But what has happened to all that tradition? Where is it available? Some cuts – those of the War of 36 and those of Franco – completely condition the transmission of literature in Basque, it is necessarily a court. The late standardization of the language does not disturb the issue either. Needless to say, the diglosic situation of the Basque Country does not yet have an easy way out on the horizon.

The reality is that books in Euskera, in general, rarely have a second life.

We could continue to outline obstacles, as Lertxundi did with literary ceries. It has been sought that the authors of this tradition translate to current readers, and in the expression “contemporaries” is meant continuously, so that the reference works are also a reference to a few years of its publication or reissue. The reeditions of some modern classics that could be found in the editorials Elkar, Alberdania and Erein, have remained very few and obsolete, have not been renewed. XX published by Susa at the beginning of this century. In the Poesia Kaierak collection of the 21st century, collections of forty poets were published, which constitute an essential canon, but without updating the spelling, and the collection today is barely in circulation.

The reality is that books in Euskera, in general, rarely have a second life. There is no habit of republishing and there are no usual pocket editions in the French literary system and in American English. This lack of habit also makes for less excuse for having to revise the spelling at least, but in some republished works this work is not done to the detriment of the readers.

Adaptation?

Koldo Izagirre says that the word adaptation should be used with care. He says that only spelling should be updated and obvious errors corrected. He insists that the difference between the times of the mountain and those that are plain is also literary. That these works must be corrected, but above all because they were published without editors or almost pre-readings, without professional opinion. Literary writing in Euskera needed to be solitary, and these authors remain alone, almost without readers.

Some works have been reedited by units, others in specialized collections such as Poesia Kaierak, but it should be otherwise. As Lertxundi says in the preamble of Bihotz-betan, popular editions are needed. Izagirre insists on the idea that these tasks should be accompanied by annual production rather than whim.

It should be a systematic work, to review the literary tradition in Euskera, to draw up a list of the works to be brought to the new readers, to draw up editing plans and to carry them out. An example can be the Hauspoa collection, which drinks from the Auspoa collection by Antonio Zavala. The reissue of the novel tirako nizkin (1964) by Sebastián Salaberria began the collection, translated into the unified Basque Country, so that “the young readers have more access to this classic of Basque literature”. The observations made by Pello Esnal clearly indicate the criteria followed and the choices made for the work of Salaberria to contain the Basque.

One thing

and another, the reality is that old books don't have new readers. On the one hand, because physical specimens are not available. On the other hand, because the versions of the existing texts are not useful on a daily basis. Another debate is where the limits of adaptation lie, but in renewed editions at least spelling should be updated. In fact, if the whole tradition is not available, or some representative specimens of it, a literary canon increasingly linked to the last thirty years, of short roots, is remaining in the Basque literature.

"It will be true that our literature is reduced, but I think we have not read our restricted"

Koldo Izagirre

By way of example, we have asked Koldo Izagirre to start the list of works that should be carried out in the circulation and he has responded appropriately: The story of Xabier Kintana, the collection of poems by Arantza Urretabizkaia, the novel by Jean Baptiste Elizanburu Piarres Adame, the book by Juan Antonio Mirandez in the Parentheses of Juan, the book by José Antonio Mujika Itzalak, the article by Jon Miéndere.

It's just the part of a possible list, a small part. Izagirre says: “I brought them out looking at blocks A and M from the Bridge – which was in the head of Lizardi and Txillardegi-. Those are the ones published, of course. But there are other interesting papers in the press: articles, chronicles. It is usually said that our literature is small, that it has not been written much… Of course it is true, but I think we have not read our reduced.”

Astelehen honetan hasita, astebetez, Jon Miranderen obra izango dute aztergai: besteren artean, Mirande nor zen argitzeaz eta errepasatzeaz gain, bere figurarekin zer egin hausnartuko dute, polemikoak baitira bere hainbat adierazpen eta testu.

Martxoaren 17an hasi eta hila bukatu bitartean, Literatura Plazara jaialdia egingo da Oiartzunen. Hirugarren urtez antolatu du egitasmoa 1545 argitaletxeak, bigarrenez bi asteko formatuan. "Literaturak plaza hartzea nahi dugu, partekatzen dugun zaletasuna ageri-agerian... [+]

1984an ‘Bizitza Nola Badoan’ lehen poema liburua (Maiatz) argitaratu zuenetik hainbat poema-liburu, narrazio eta eleberri argitaratu ditu Itxaro Borda idazleak. 2024an argitaratu zuen azken lana, ‘Itzalen tektonika’ (SUSA), eta egunero zutabea idazten du... [+]

ilbeltza-(1).jpg)