"I think poetry is a place to do something more with words."

- Itziar Ugarte Irizarren (Oñati, 1995) Gu gabe ere (Susa, 2021) is the first book of poems that immerses the reader in the waters of absence and presence, memory and life. The interview has been a good excuse to meet two old friends of the literary band ITU and dedicate themselves to poetry.

The book is published by a quote by Louise Glück: “Beautiful things, he said, / you have them in front, or maybe behind; / it’s hard to be sure. And he added, is there any difference?”

Everything is there, in that continual impoverishment. Your present, which will become a memory tomorrow, is based on bigger things, more collective memories and conditioned by broader conditions. The quote says “it’s hard to be sure,” and it seems that the other side is the most important, but for me uncertainty is very important. Mariano Peyrou says that poetry also teaches us to accept the uncertainty and mysteries that surround us in everyday life, and that gives you a breath to be able to assimilate things as it is. In the book, memory is a very important axis, but not the one related to the past, but the one understood from the present and the future.

There's a very important moment in the book: our two grandparents and a grandmother died very closely, and for me it was an intense moment. As I was going to another speed and vitality, it caused a huge collision. I felt very close to decay, and I realized that I was coming at rather slow speed to get into it. A poem says “I wanted to be there” and it helped me to be there and become aware. I realized how the person is losing his memory, I think it is too. Hence a dialogue with them and their generation to find out what my worldview has done. The exercise has been to delve into it and understand what unites and what differs from the blood link, understand why its way of life has been, what its relationship with its environment has been, with what language of relationship. Despite the physical absence, you still carry that shared framework. Your collective memory is also part of you, and your individual consciousness is completed at the crossroads of many collective memories. So even if a particular memory is lost, others follow. For me, it was time to awaken many questions: that concern for memory, and to see what we do with our time, with our time ... I have a lot of notes and images from then, and from them I've written a lot of the book, but not just from there. That's how I understand the book, but it's very possible for someone else to understand it, and that's nice, too, from another place.

There's an impulse to understand that world that's not ours, but that also does us, but also to analyze what we leave.

Yeah, that's it. It is, above all, an awareness. What do you do when you take a place where a lot of other people have been around. Memories are a very fruitful material for it and for thinking about other things. Sarrionandia spoke in a text, and I really like the idea, how individual memory is also related to the material and moral life of the society in which we are part. This makes it share what is your most intimate memory. I thought that one of the concerns related to the book was that, when referring to an area as close as the mother, the father, the grandmother, had a little transcendence without overvaluing my experience, and then the reader would find a place to have their own experience with the text. When we started thinking about how to explain the book, it played a lot to that moment and to some ideas, but editor Leire López said that the poems of that time are not so much and that there are other things. And it is true that there is a voice of a young man, eager to repress his time as much as possible, to savor. That pleasure and vitality also has its place in the book.

The images have a lot of weight in the poems, they are accurate images in general and the language of the poems is accurate, we note the concern for the return of the word.

I think poetry is a place to do something else with words. A place to take further to do something other than your daily communicative function with language. The choice has been to tell simple words more than they normally count. There's different poetry, but there's a false belief about what's thought poetic, that poetry needs a swollen tone and a complex language. I don't know if it's a choice or a voice that overflowed when I wrote, but from one point I became aware that that transparent language served me when I wanted to count. Ruper Ordorika mentioned in the previous article: “Singing to get to simplicity requires a lot of crushing,” and that work attracts me, how to make visible what is with simple words. When I rewrote some poems, when I was starting to shine, to charge and to raise the pitch, I saw that the poem was starting to fall. I've been on that border, how to get something else done with language in a simple way.

There's a very own lexicon. It seemed to me that sometimes it is the language itself that leads to some memories. In the

poem of the bleaching of the nuts appears how the grandmother said “in the breeding area, in the defecating area”. How many things can be behind this. A woman of the time tells her that whether or not to be a child was not a choice, but came by herself, which gave a concrete form to her life. He didn't have the input we've had, if you will, to some studies, for example. But their rich reflection was, without all that, how they had a huge camera, both of language and of their own experience. In the poem Zuloa also appears the voice of another very mature woman, and I am interested in providing her ability to tell and her words. We relate to the environment through language, where there can be a lot of information.

Smoke appears in the poem as a concern to talk about writing rather than writing. He's been writing for a long time, but now he's published the book, how does his desktop live?

There's one thing that's given him a lot of laps. It is important for those who write to think about writing, to reflect on the instrument you use. There are more poems about writing in the book, and in the poem "The Songs of the Father," there's that concern about creative work, how we live this. The desire for words is asked in the poem “what gives meaning to what?”.

How do I live it? Sometimes with that noise. I take out the writing intervals in a staggered way, and when I have time, it produces a little bit of outdated noise with the readings or without taking time to write. Also in the UTI group, we had that ghost behind us. I'm sorry very close, I'm wearing that "you should be writing" with me. But why? Who is waiting? I live with that tension.

I am happy with my own courage and confidence, with the work and with the presence here. Now I have more determinations, and I want to spend time on this, writing and reading, making room in my everyday life. I've had a very long time tied to writing and I've enjoyed a lot, conflict. However, it is difficult to keep it later, I work writing and sometimes it is difficult to go home and put it back in front of the computer and between papers. Unfortunately, the brightest moments of the day don't do that. I do not know what I am going to say in a few months’ time, but at the moment I feel like doing so.

The skin is dressed in an image of Nagore Legarreta. It has color luminosity, but also some shadows, are easy to connect with the interior. Where did the idea come from?

Until very late, I didn't think about the skin and other elements, and I was advised to go to an artist or illustrator that I liked. A lot of poems are memories, moments are gathered, and I saw that a photo could be appropriate for the front page, but I didn't want the one about a family file. The photo technique encouraged me and I proposed it to Nagore. I'm drawn from his work that they're very blurry images, and this stenopic camera technique, also images that are printed over time. We went without saying anything too much, in search of what suggested reading the poems to him. He proposed to make a roadtrip from Egia to Oñati, making stops along the way, we would take two reels and from there the skin would come out.

In your work process, Nagore leaves you lucky, and I find that trust beautiful, to leave things without you imposing them too much. I had as a starting point a greenhouse in my head, which appears in one of the poems. In the end we started there and it was strong, because it came and Nagore immediately said, “Well, that is, the site, we will throw the two reels here.” He himself had highlighted someone who is leaving somewhere and crossing roads, and we started doing tests.

It was a very beautiful, sunny autumn morning, in which we spent a while searching for images. He was then placed with scanned crystals on them in layers. I am pleased with the result.

For me it is very nice to see what echoes are produced between the poems and the skin. It's very free, everyone sees their stuff. When a friend saw the blue line crossing the skin -- I wasn't conscious -- the blue line came to mind, which sometimes comes out when recording with the Super-8. I found it beautiful, because the Super-8 has been used many times to record the home environment, and there's a game of this kind in poems, a way to look at that nearby environment. I really liked it when people said that they have found a bright book, an effort has been made to impose it, and those rays of skin kindness I think they can pick it up.

Did you intend to group these poems in a book from the beginning?There have

been two rhythms in the process of creating the book. On the one hand, I've been collecting poems for four or five years, which have been drifting through the stack a lot. Not at least with the perspective of any form or project. The experiences and notes of then have been the muse for poems. Then there has been another rhythm, last year. At the beginning of the year, we began to make the idea of the book more present and to analyze the material it contained. I didn't want it to be a collection of all the poems I had, but I wanted to build the book with a sense. With this perspective, poems have also been created.

The end has been narrower, but I've learned a lot. I've looked for reasons and speeches to things, to see what's behind poems, what topics, where to build the book. At one point, everything starts to be questioned. Poetry is also moving away from wanting to do everything exposed, and in that clash I've been fighting with some things.

Poems go one after the other, there is no explicit structure, has there been a temptation to sort them differently?For me it was important

to build a book, and not have to take the poems I had and stick them in a single file. That's one of the things that has cost me the most, to look at how poems worked, how to sort out the story of the book. I did a test to divide it into three parts, and it helped me realize that I didn't need any sections. The scaffold was very forced, that poems didn't need. There are many echoes between poems, and the structuring broke it. There's a voice that picks up and takes a relatively easy leap from one poem to another. The challenge was to recognize that I did not need a section and how to complete this continuum, how to modulate the succession of poems of one type and another to draw textures to the story. It's often a mystery, you don't know very well where the poem will be brightest. The first poem, the mother in front of the sea, for example, is a very small poem and in principle it was inside, but the first poem became the recommendation of a friend. There he has found the place of growth, probably because it would be more covered inside. It's a great mystery, and in this case, for me, conversations with the readers of the book are very useful.

The readers have been the editor,

other people from Susa and friends close to the literary world, and for me Iñigo Astiz has been very important in the process. We have a quite redeemable poem, and that keeps you in tension, keeps alive that desire to go back to text and sharpen. As he himself says, he keeps the fire on. I've learned a lot in that exchange and in exchanges with other readers. I think I've been lucky enough to have people around to show and share jobs. In the times of the ITU Band we also had the opportunity to do things at once. It's written by a lot of people, and not everyone has that opportunity. Not only to publish, but also to improve and share. This work of fronton is enriching.

The book is bright and open in many ways, beauty has its place, but that clarity is permeated by shadows and violence.

Yes. I think there's one important thing in the book. For example, in that "no." Then I've realized that there are a lot of absences in the book, the places that have been left behind, the people, the relationships, the times -- and at the same time there's this idea of accumulation, that tension. Lose and add. The stack is also made, there's no more. I wanted to take it with a light attitude, to become aware, to become aware of it, to celebrate it as well. We'll have to figure out how to make room for those places and those people that we're accumulating.

Returning to the moments, there is a will to celebrate and enjoy those things, to give place and to recognize the ephemeral. In the book there is also pleasure, very varied, but there are also underlying conflicting mechanisms. The passage from pleasure to violence can be easily done, as Iñigo suggested in an interview in Berria, which crosses very tenderly from one side to the other, and the fragility of these things is in the book.

Pleasure in one female body is not the same as pleasure in another. Celebrate then good and beautiful things, but not forgetting what that is built, and what order and what pain is ahead.

Istorioetan murgildu eta munduak eraikitzea gustuko du Iosune de Goñi García argazkilari, idazle eta itzultzaileak (Burlata, Nafarroa, 1993). Zaurietatik, gorputzetik eta minetik sortzen du askotan. Desgaitua eta gaixo kronikoa da, eta artea erabiltzen du... [+]

Entrepreneurship is fashionable. The concept has gained strength and has spread far beyond economic vocabulary. Just do it: do it no more. But let us not forget: the slogan comes from the propaganda world. Is the disguise of the word being active buyers? Today's entrepreneurs are... [+]

Spring is usually a promise of a cold winter nose that can come after the landing, and has been annotated several times for sleep. Promise, however, is never a safe spring in a ruined terrain. Not at least if we are talking about change or, in particular, revolution. Maddi... [+]

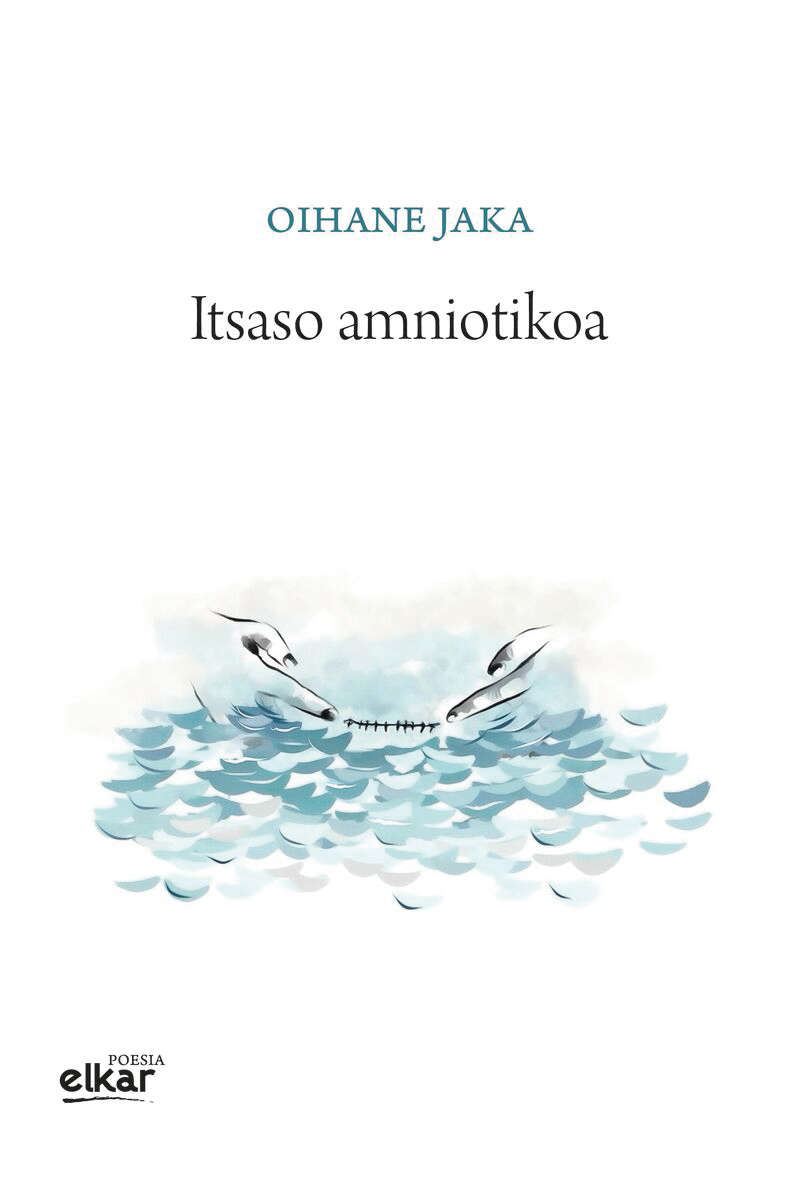

We opened the poems book by Oihana Jaka and found two deals. One father and another son. It is worth noting for its direct relationship with the poems we will find. The book is structured in three parts:

Hamaika urte, Hamaika hilabete eta Hamaika egun. Number eleven is also... [+]

Yolanda Castaño has been interviewed since she received the Spanish National Poetry Prize. The head of a row from one of them caught my attention because he said the second hardest thing he's ever done is win the prize. And I immediately began to look for what was the hardest... [+]

A few years ago, I wrote a little book about Tene Mujika, which is called Udazken Argitan. When I started doing that biographical essay, I met our protagonist today, Mr. Watson Kirkconnell. In 1928, Kirkconnell published a nice book of European Elect anthology, which included... [+]

I do not remember who I heard that at the end of the month you can only write poetry, if poetry is not your way to the end of the month. Poetry, fortunately or unfortunately, has always been on the periphery of the literary system and the cultural industry. In any case, poets... [+]