- Aberdeenshire (Scotland) 8,000 years ago. Humans built a megalithic monument composed of 12 stones that gathered the positions of the moon throughout the year. So this kind of lunar calendar is the oldest known calendar.

5,000 years ago in Mesopotamia they also used the lunar calendar, which divided the year into 12 cycles, but the Babylonians and Sumerians realized that it did not match the solar year, and every four years, they added a long month to sort of fix the gap.

The first solar calendar was invented by the Egyptians about 3,000 years ago. Egyptian astronomers and mathematicians calculated that the year was 365 days, and so at 12 months of 30 days they were added 5 days to complete the solar year. In addition to the ocean, the Mayans knew that the solar year lasts 365 days, and about 2,000 years ago they drew up very precise calendars, such as those they used in the Roman Republic.

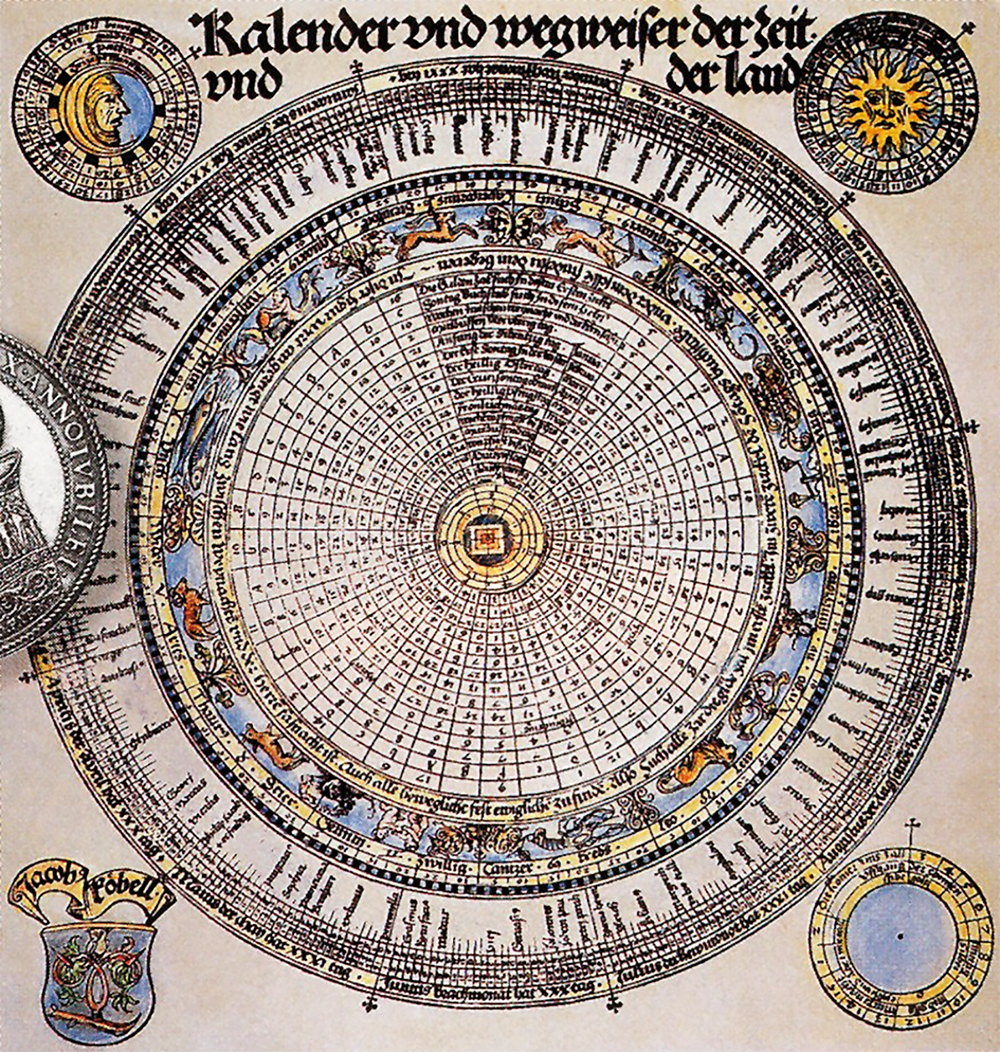

a.C. Until the seventh century, they used a 10-month and 304 day schedule in Rome. Then, a further two months were added and the 355 days began to be used. When Julius Caesar travelled to Egypt, he saw that there they were using a much more precise timetable and, based on it, and adding visas for the first time, he established a more precise timetable that would be used in the West for 15 centuries.

But the Julian calendar had accumulated 10 days of lag by 1582. That is why Pope Gregory XIII commissioned and implemented a more detailed timetable. The physician and astronomer Luigi Lilio elaborated the new calendar and suggested gradually increasing the accumulated gap; instead of adding a single day in each biennium, if we add two, in 40 years the problem was already solved. But by then the pope was already dead and Gregory wanted immediate results. He decided to eat 10 days in a bite; the day after October 4, 1582 was October 15. Thus, the pope obtained at least one confession, known as the Gregorian calendar. But it also caused other problems.

Many European citizens and local authorities did not enthusiastically accept the Pontificia’s decision, as they believed they were being robbed of their time. Consequently, in some countries the new timetable was immediately implemented, but others did not update it until the twentieth century. This caused a series of vicissitudes in historical dates during the years and centuries after. For example, the writers Miguel de Cervantes and William Shakespeare share the official date of death (23 April 1616), although they did not die the same day, and according to the Gregorian calendar of November of the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917.

And it also failed to definitively solve the problem of the mismatch, because the Gregorian year is 26 seconds longer than the astronomical year. This means that in 3323 years the one-day lag is accumulating. Astronomers have planned a far-off solution to correct this small margin: The year 4000 will not be bisiest and the year 8000 will not.