“Society strives for art to have an immediate effect, and it doesn’t.”

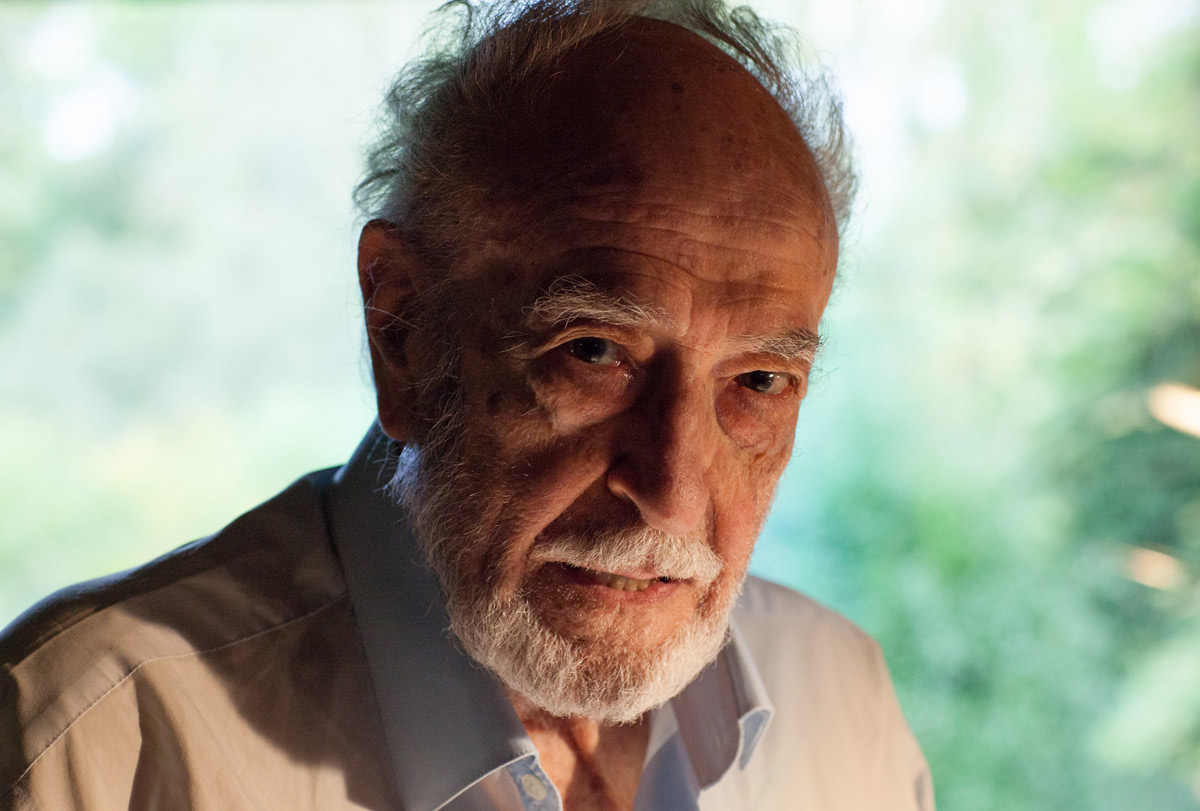

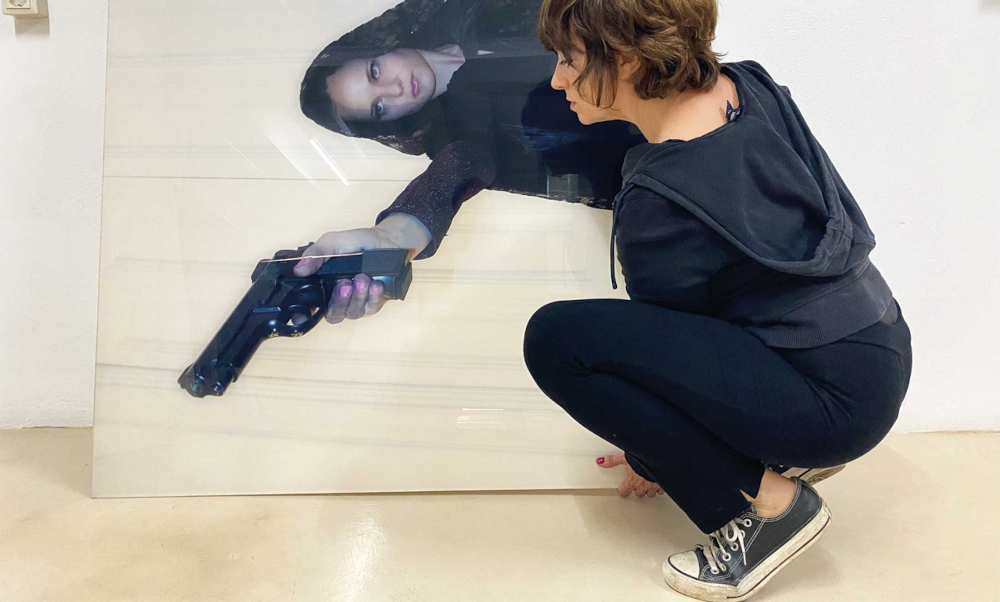

- Sculptor of “radical aesthetic”, says Wikipedia. In fact, Ana Laura Aláez (Bilbao, 1964) uses unusual materials and views in her work. Until day 26, at the Azkuna Zentroa in Bilbao, “All concerts, every night, every empty” (All concerts, every night, every empty) is your most ambitious exhibition. With this excuse we have addressed him, and this semi-biographical conversation is born in our hands.

You were born in a family of workers, it is a possible beginning of your biography.

That's right, and I'm proud. Because in my generation art, art, seemed forbidden to people like me.

Why?

By gender and social class. Art was not within the reach of class workers. On the other hand, I insist that I belong to a family of workers, of him, and of those around me, because I have received some work attitude. Instead of complaining that things are working badly, trying to do things. They said to me, “You’re crazy, you’re not going to have a chance,” that is, the possibility of practicing fine arts. And one day I thought, “Leave me alone, I will make my own way.”

And enroll in Fine Arts at the UPV/EHU. Did you already have the idea of being an artist, or sculptor (whatever)?

Not much less. I finished the COU and my instinct told me that I could always draw and paint, that is, as I was skillful for the two-dimensional, I could go to the Faculty of Fine Arts. Having that opportunity was a privilege that I wasn't used to.

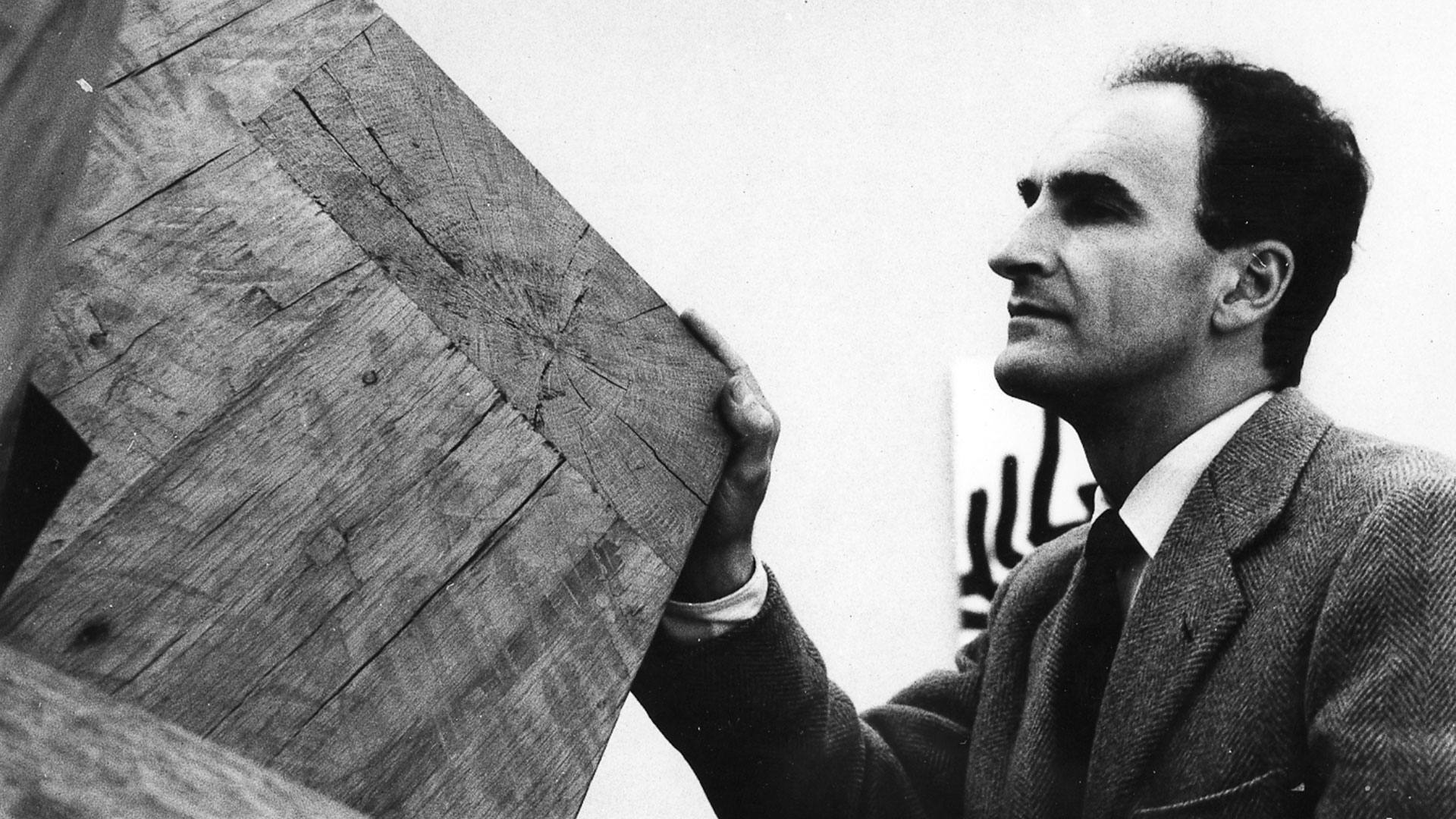

Did I think of the word “sculpture”? At that time, in Euskal Herria the shadow of some sculptors was long: Oteiza, Chillida, Mendiburu..

I was anxious to learn everything I had around me, about youth. At first I tried to convince myself that I had to do something that was as close as possible to what was estimated in my environment. But I started to notice that matching what others do is not satisfying, and that copying is easy, but feeling that it's not that easy. From the beginning, I thought it would be interesting, as an artist, to walk up, to question things. You don't want any conclusions, you'd rather ask yourself, and so the answers of others aren't valid either.

In “All Concerts, Every Night, Every Empty” it becomes clear that you’ve broken your way and no one else’s. Was there a certain moment, a click that made you decide to work with other molds from the material point of view?

Yes, there was a special moment. I finished the Fine Arts and went to New York, with my bare hands, but with the feeling that I had to leave. My hometown, somehow, kicked me out, there was a galga, because at my own university they told me that what I was doing was interesting, but it wasn't a sculpture. And in the city of skyscrapers, I felt protected, not because the doors opened to me (I had no galleries or any), but yes because the others did not question me. I started working with the materials that I had at my disposal; they were very poor materials, because I didn't have the ability to buy the usual sculptural materials, and on the other hand, what I was doing had to be transportable afterwards, they had to be artwork that could fit in the suitcase. Cheap and very small.

In the exhibition you see that one of your favorite materials is clothing...

This comes a little bit before you go to New York. I learned that in order to work, you didn't have to wait to be in a better economic situation, and that whatever surrounded me, in any case, could become material. If I couldn't get anything, I would open the closet and start working on what I had found there.

You have gathered in the exhibition many of the pieces made throughout your career and explained that they complement each other. That is, it is not a mere collection of works performed by Ana Laura Aláez in her life. Is there any idea that summarizes everything you wanted to express?

Maybe I still don't understand what sculpture is. I have to say, on the other hand, that this is no other exposition. I've done it with the viscera, and I think it replaces me perfectly.

You say that when you started, not only by social class, but also by gender, you did not have to be an artist. Is the demand for gender fundamental to you?

It is not a question of claiming anything, that is very ambitious. I can't change the world, nobody can. So, I don't claim gender, I'm just talking about my own experience. The word “proclaim” isn’t the most appropriate, it’s the word “use” when you get something. Shareholder reaction. And art doesn't, I don't think, at least. Because society strives for art to have an immediate effect, “I teach this and something happens,” and that’s not the case. That is not the case. Do you read a poem and that claims something? Everyone has the right to do what appears to be of no use at all. The word “claim” has a tone of functionality, and functionality is still something long-term.

weeks, until the eve of the day when we talk to Ana Laura Aláez, it was possible to see in the Museum of Fine Arts of Bilbao a video-creation of it: Queer carriers: double and repetition (Queer carriers: double and repetition). “The title holder is a very special word for me,” he explains, “because it is the name of a photographic exhibition I made in the early 1990s. I’ve always thought that people are carrying sculpture, perfect plants for sculpture.” At Portadoras queer, Aláez recognizes that she has recovered several forms of work that she had self-absorbed.

On Monday afternoon, I had already planned two documentaries carried out in the Basque Country. I am not particularly fond of documentaries, but Zinemaldia is often a good opportunity to set aside habits and traditions. I decided on the Pello Gutierrez Peñalba Replica a week... [+]

The search, the continuous search for a path, implies discovering what we do not want or expect. An artist should feed this appetizing search if he wants to keep his spirit alive. Your career is also going to need a big head office. Looking for new ways, uncovering and expanding... [+]

I get contradictions in art competitions. On the one hand, they place artists and works of art within the dynamics of competitiveness, leaving aside the transformative and collective character of art and placing them within the mercantilist logics, but it cannot sometimes be... [+]

Eskuin muturreko ekintzaileei leporatu diete eskultura bandalizatu izana: Hau kaka euskalduna da idatzi dute frantsesez, eta Heil pepito agur nazia margotu. Jean-René Etxegarai auzapezak jakinarazi du salaketa jarriko dutela. Gainera, Frantziako Alderdi Komunistaren... [+]

In the Plaza de los Fueros de Vitoria-Gasteiz there is a new metal sculpture that welcomes the exhibition of Nestor Basterretxea (Bermeo, 1924 – Hondarribia, 2014). The exhibition brings together more than 300 works created by artists from different areas, such as posters,... [+]

Ekainaren hasieran zabaldu zuten Santa Klara uharteko (Donostia, Gipuzkoa) itsasargi zaharberrituaren atea. Barruan, Cristina Iglesias artista donostiarraren eskultura: Hondalea. Denbora gutxian agortu ziren artelana ikusi ahal izateko txartelak, museoaren eta eskultura... [+]