- In May, a Canadian college in Kamloops detected the body of 215 children buried. They belong to “savages to civilize”, that is, to the autochthonous people who before the arrival of the settlers lived in their land and their land. In order to assimilate it, the Church and the Canadian State organized a system of schools and forced internships. From 1831 to 1996, the interiors were extended, with a total of 150,000 children. Those who came home were shattered from this calvary by cultural, emotional, psychological, physical and sexual attacks. Thousands of others died: officially some 6,000, although they may be many more and at the moment it is not known how many are not counted stored underground.

In late May, 215 children buried in a Canadian school in Kamloops, British Columbia, were captured. It's not any class or any child, and precision reduces our surprise, as if place and bodies gave us a logical explanation. From the beginning of the 19th century until the end of the 20th century, the remains of 215 children considered “savage to civilize” have been found in a school intended for indigenous children.

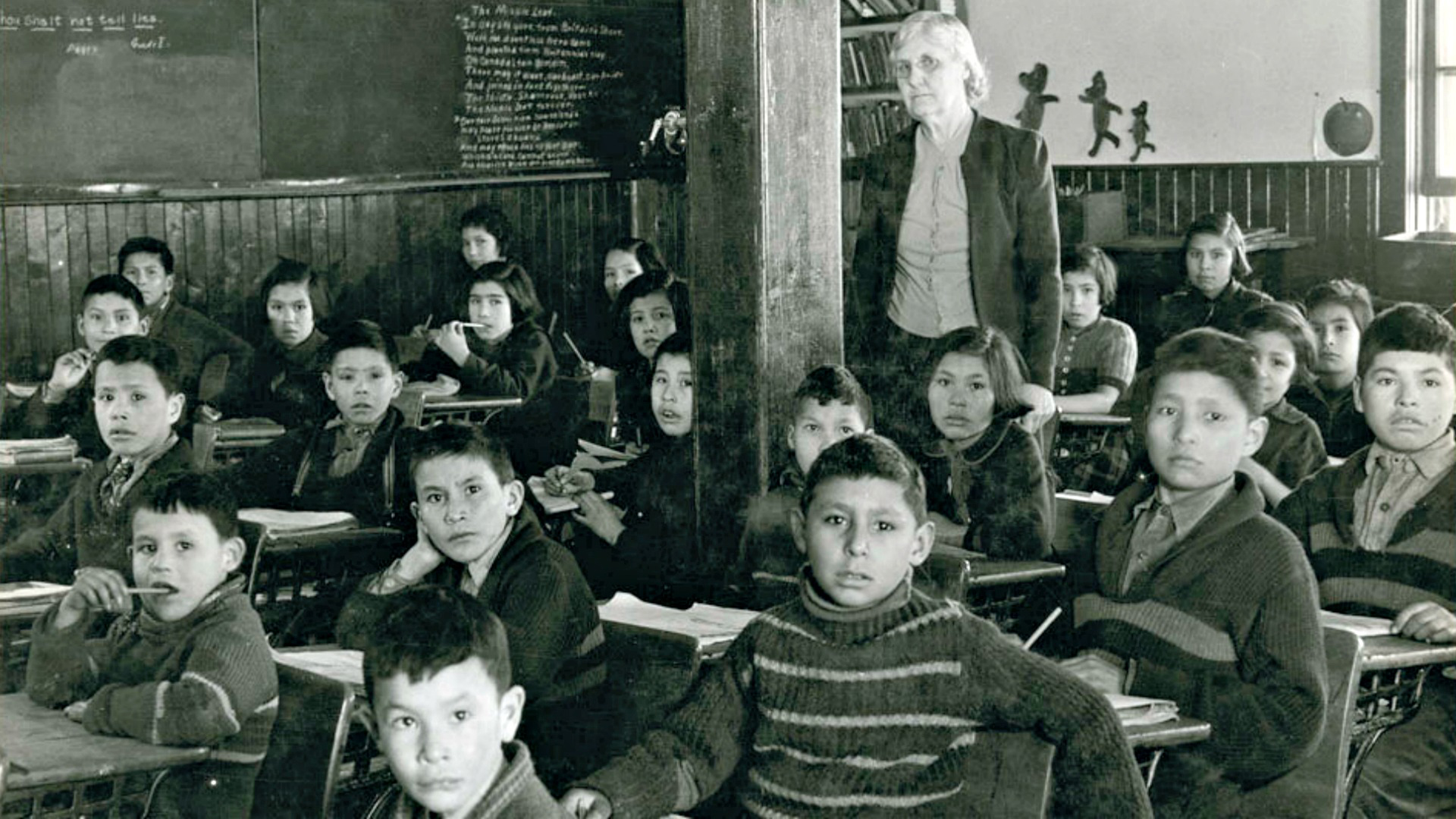

Officially, the Canadian State and the Church opened these schools with the aim of “killing their Indian.” Every non-white child had to pass through his childhood, that is, those of the First Nation, Metie and Inuit. Both the State and the Church were aimed at preventing all their Aboriginal language, culture and heritage. One was lost, another was dealing with those typical bodies and souls that had to be filled with Western values and Christian values.

From the age of three or four, these schools were the place where missionaries separated from their parents, burned traditional clothes, cut their hair, prohibited mother's language, refuted beliefs, imposed a new name... They were basically more than schools, because they were also hospitalized: they had children kidnapped and had to survive in the imposed world of settlers. In 1892 the boarding schools were officially generalized and in India of 1876 the adaptation of the segregationist law Act of 1920 supposed that all the locals had to spend ten months in boarding each year between the ages of seven and sixteen years.

They lasted between 1831 and 1996 and in total 150,000 people went through these 139 boarding schools throughout Canada. You have to see the documentary Tuer l’indien dans le coeur de l’enfant (“The Indian in the Heart of the Child Dies”) by Gwenlaouen Le Gouil - www.arte.tv which can be seen until 11 June with subtitles in both French and Spanish. “They have destroyed us. Destroy the children who wanted our land. What did I do to have to endure that? Nothing, he was a simple child,” explains one of those who had to spend his childhood at the barnetegi Saint Anne in Fort Albany. In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, set up in 2008, published a clear conclusion: these schools and boarding schools saw a “cultural genocide”.

Destroyed and traumatized

It counts how she was electrocuted twice at seven years old. “It’s very hard to get up from all that... you wake up one morning in alcohol or in prison.” His colleague narrated that the nights were spent in ikaran because at any time the rapist priest could come to him. “Most of us don’t know: suicide, overdose... I will also throw a shot at myself, take a quick dose again in the hope that I will never wake up... it is terrible and I find it hard to tell verbally,” says another who has been raped over and over in boarding schools.

215 bodies have therefore emerged. What was the cause of his death? Too fast an electric shock? A murderous violation? Have you drowned in your vomit – yes, the testimonies of the abducted children show that you had a habitual obligation to swallow the vomit again? That too harsh living conditions have led to the disease? Famine? Suicide? All of them are possible reasons, because they were all part of their reality.

It is known that there were deaths in these boarding schools – a long time ago also: in 1907, doctor Peter Henderson Bryce reported that the mortality rate was 25% in boarding schools and that the exit rate was 69%. According to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, we can hardly know how many deaths, but officially there are at least 4,100, a minimum of 36 children, and it says that they can be more than 6,000. Surely they are more, seeing that, as now, the remains vary at some point. The committee is collecting testimonies and with 6,500, the cases of those who never came home are traumatic.

The Ministry of Indian Affairs forced the deaths to censor in 1935. The lack of determination of the censuses clearly reflects that these bodies lacked value and that, in the end, they were alive or dead, they resembled the Church and the State: a third of the deceased appeared without a name, a fourth without defining gender and a half without determining the cause of death. It is obvious that, like these 215, which were finally discovered, you can't tell the number of guards.

The existence of unidentified sinks is well known, and for decades those of the First Nation have been using the search work to address the barriers and prohibitions imposed by the authorities. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission itself acknowledges that family members were often rejected from the recovery of bodies charged with typification of expenses. The victims also recall that in 2009 they were refused the subsidy for the search tasks.

In 2008, Otawa forgave those of First Nation for the horrors of the inmates, and gradually, slowly, on the road to reconciliation, the federal state – accelerating the pace since 2015 by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau – is taking steps.

Tobacco: Although not mentioned, the wound remains open

The survivors of the boarding school were torn apart. All of them were returned to their families, lands and communities marked by physical, sexual, cultural, emotional and psychological assaults. This past has been silenced by the majority, in the hope that its conservation would be forgotten. But, as it maintains, in the age of bread of every day the children and the elderly of today, as well as their descendants, have discomfort. Two data on trauma transmitted from generation to generation: 58% of Canadians aged 15 to 17 depend on alcoholism or drug addiction... and they also have a suicide rate twice that of Canadian whites.

“My grandparents and my grandmothers survived, I didn’t fully understand why they didn’t tell me anything at all. Today, half of the children in my community are cared for by the State, still with Social Aid for Children, we are ill”, tells a parallel journalist a young native who was at the meeting in Montreal to denounce the discovery of the dead bodies and the genocide suffered. Yes, the past and day-to-day are too black for children and young people who are still concentrated in reserves to live in freedom and who depend on the Act Segregationist Act in India of 1867.