"Cinema is not a tool to work concrete messages or theses"

- Mexican director Yulene Olaizola sees cinema as a sensory experience: she discovers and explores a space and has the senses alert for any change beyond the script. The fifth feature of his career, Selva traggica (Oihan tragica), was presented at this year’s Film Festival. He was not in San Sebastian because of the pandemic. And he doesn't know if he'll be able to present it in theaters.

His first film, Shakespeare's Intimities and Victor Hugo (Shakespeare's Intimities and Victor Hugo), was presented at the San Sebastian Film Festival in 2008. Yulene Olaizola (Mexico DF, 1983) was in Donostia-San Sebastián and unbeatable memories come to his head. “The film was very welcome and I was able to know a little more about my roots.” His grandfather was from Azkoitia and his grandmother from San Sebastian. “In times of war, Mexico had to be exiled.” He won awards with that unusual documentary film that told the story of his other grandmother here and there. The three films that followed him did not echo as much: Artificial havens (Artificial havens, 2011), Fogo (2012) and Epitaph (Epitaph, 2015). This year I had a special illusion to return to Donostia: “It has been impossible for me because of the pandemic and because I am pregnant.” The tragic jungle, the fifth of her career, was offered in the section Horizontes latinos. It is a story set in the border jungle between Mexico and Belize, based on a legend transmitted from generation to generation by the Mayan community, which brings together the beauty and crudety of a wild life, facing sensuality and death.

We get in touch with Olaizola via Skype. She teaches at the Mexican Film School DF. He teaches film direction. “I love teaching. In addition, this school was created in a very alternative way. Not following rigid teaching plans. Professors propose themes, dynamics, etc. It's a very free school, and students can experience everything they want. Most of the teachers are filmmakers, and that gives a lot of dynamism.” Brand new Jungle tragic in the cinema circuit and come to Euskal Herria with the intention of making a film, among other things.

At the beginning of the film Tragic Jungle, the narrator says that the jungle takes away as much as it has given it. Does film also give it and take it away?

Yes, film gives you and takes you away, but I'm sure it's given me more. Film requires great involvement and a great deal of the day; dedicate life to it. I am at least constantly thinking about my projects and films, about the content of my films, and when I get home, that wave of thoughts does not stop. In addition, if you have a fairly independent way of filming – as in my case, I assume all the areas of filming and production – they become very personal and related processes. And that also transforms and shapes my life.

For example, when you decide to roll in the jungle for two or three months.

Yes, during those months all my dynamics have been transformed; personal, family, etc. In addition, before I rolled, I spent another four or five months. The jungle entered my life, it got into it, and that can't be avoided, and that's exactly the good thing about playing movies; otherwise, I can live adventures that would have cost me living. The land was very unknown, unknown to the locals and their stories, the jungle rising on that vague border between Mexico and Belize. Before entering the project fully, I also knew very little about the relationship we Mexicans have with Belize. I didn't know that a very narrow river is bordering and that, if you like, you can cross a canoe or even swim. I didn't know that in Belize they speak English officially, I didn't know that the Mayan culture is still very present, the whole mix of culture they have there -- African, English, Maia -- what relationship they had with Mexico in trade and what relationship they still have. For example, chewing gum. It was a very important industry, it moved a lot of money, among other things, at the time of World War II, from which a lot of chickens came out. I didn't know that reality or that land.

The jungle itself is an experience. Also a character in the movie, perhaps the most important. Has the challenge been not to idealize it and not to demonize it?

No doubt. When I started researching, I read mostly literature books, and Mexican writers represented the south of the territory of Quintana-Roo as a living entity, the jungle as a character, and as a decision-making element. They were stories created by the Mayan culture and the mitos.Todo that brings a very romantic, nostalgic, mystical and magical imaginary -- but once there, once there, you walk into the jungle, you make long walking tours, you chat with the people there and then you understand all that. Very strange things happen in the jungle, and you don't always find a rational explanation. Once there, you lose the sense of location, you know you're surrounded by thousands of animals and creatures, but you don't see them, and -- stories, myths, legends arise and they're passed down from generation to generation.

“When you’re in the jungle, very strange things happen and you don’t always find a rational explanation.”

The jungle is hard and raw, but not as hard as human intervention.

That's one of the ideas that goes through the movie. Cinema is not a tool to work concrete messages or theses. But I had some ideas in my head, from what I've read and heard, and I've tried to reflect them through all the layers that could be in a movie, with the story, with the landscape, with the characters ... I have understood that the jungle can give us a great fear of men, especially those of us who come from the city, but that it cannot be equated with the darkest part of men either. This reflection is more topical and powerful than ever: we are the most dangerous plague in the world, and not a beast or a poisonous plant. Human beings will always try to cope with death, avoid it, forget it, but the rest of the living beings live that relationship in a more organic way, in a more normal balance, in a natural cycle. We are the ones who destroy this cycle.

The film speaks of a legend of that forest, of the fascinating ability of a figure with a female image.

It is a well-known legend in the country where we rode, known as Leienda Xtabay, both in Quintana Roo and in Belize. I was surprised that in Belize, even though English is spoken, this magic legend is still strong. It can have a lot of readings and interpretations. Most of the men in the village of this territory claim to have seen that female figure. History has been passed down from generation to generation and reflects in some way the game between life and death, sexuality and risk. Almost all Latin American cultures have a similar figure, although each one has its own characteristics. It has been almost universal to have an image that symbolizes that connection between femininity and death, to unite sensuality and risk.

The film will also have more than one reading in these times of demands of feminism.

Yes, he intuited that he would stimulate his reflections, his questions, his questions. And I'm aware of that. The film explains in a more abstract and poetic way, metaphorically. In other films it would look more directly, in mine it is shown through fantasy. But the issue is latent and it's latent because it's a reality, and I, too, was inspired by my personal situation, the sensations and feelings I've had when I've lived in absolutely masculine environments. Sometimes it can be a total vulnerability, and sometimes, on the contrary, a capacity for empowerment and control through seduction capacity. That paradox is very interesting, and in the movie there are many such moments. It may not appear in conversations or verbal information, but it does appear in gazes, in the atmosphere. And then I realized it wasn't just in my head. That's where film takes hold, because it's in that sensual and dangerous atmosphere. The actress, Indira Rubie Andrewin, is from Belize, speaks only English, is young, mysterious, attractive. And a working group of 40 men around. The energies, the dynamics that are noticeable in the film, are really past. I chose to roll in that context. The actress could not verbally communicate with others and the men watched him at many times. He was in a situation of vulnerability. Tensions were forming beyond what I had written on paper.

You open paths for different interpretations. Male chauvinist values transmitted from generation to generation by the patriarchy and empowered sensuality of women.

Yes, I do not understand cinema as a tool for doctoral theses, but as a language that is inserted into other layers. Film brings together many types of information, at different levels and layers, is not the most appropriate language to show clear theses and messages.

“I like film that transforms and transforms us into filming.”

Your first film, Shakespeare's Intimities and Victor Hugo, was presented at the Festival. It was very well received. It was a very different record, but there was also the film marked by a space, an environment. Is it something that characterizes your film form?

Yes, it's something I've been finding along the way, something I've realized later. The ideas in my films have come from choosing a space first. The movies are totally different, but since on that first occasion the main goal was to tell my grandmother's story, her house became a must-have space, like the light and time in that house, etc. It was discovering my grandmother's house, every room to room, beyond her conversations and stories. The house became the character. This time, instead, the jungle. It has become a constant in my work. Before I became a story and a character, I decided I wanted to roll in that forest.

In addition, this mix of fiction and documentary...

Yes, Intimidades formally enters into the documentary format, while Tragic Jungle is a fiction, but I'm interested in not making those distinctions, and in both you can find some of the language and fiction of the documentary. Here's another lesson from Herzog. It plays with the gender limits, and it's very interesting. I like film that transforms and transforms us into filming. In front of the camera, there are living elements, and I like to catch their transformations, a movie beyond what the script says. Make decisions at every moment and that the natural changes that occur feed the film. The decision to work with natural actors has a lot to do with that, although in the film there are also professional actors. All of this increases the possibility of risk, uncertainty. Rolling in open spaces also has that, you can't control time. Here's another living variable, and it's the same nature that orders it. This adds an adventure to the creation process.

Once the movie is over, will you return to the jungle?

I hope so, but not to make another film. Now my body asks me to explore an entirely different atmosphere and atmosphere. But I owe a lot to the jungle and to the people around here. I haven't been able to come back for the things of the pandemic, and I'd like to go and show you the movie, share the experience with them. I'd like to go to those small communities and close the loop. I hope I can go soon.

Now he says he needs other experiences, spaces and atmospheres. Can it be Basque Country, being its roots?

I have often asked myself this question. And my father still, and often asks me when comes the movie I made in Euskal Herria. I don't know. I would very much like it. When I've been to Euskal Herria, I've experienced very special moments. Maybe what I need is time. Travel time and stay. There are stories out there. I came up with the jungle movie after five months ... I don't know how to work remotely. I can't write about something that happens in Euskal Herria from Mexico City. I do not work with the imagination, but with the ideas derived from reality. I've had a lot of pain because this year I haven't been able to go to Donostia, but ...

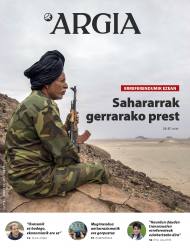

No other land dokumentalaren zuzendari Hamdan Ballal kolono sionistek jipoitu zuten astelehenean bere herrian, beste hainbat palestinarrekin batera, eta Israelgo militarrek eraman zuten atxilo ondoren. Astarte goizean askatu dute.

Donostiako Tabakaleran, beste urte batez, hitza eta irudia elkar nahasi eta lotu dituzte Zinea eta literatura jardunaldietan. Aurten, Chantal Akerman zinegile belgikarraren obra izan dute aztergai; haren film bana hautatu eta aztertu dute Itxaro Bordak, Karmele Jaiok eta Danele... [+]

35 film aurkeztu dira lehiaketara eta zortzi aukeratu dituzte ikusgai egoteko Euskal Herriko 51 udalerritan. Euskarazko lanak egiten dituzten sortzaileak eta haiek ekoitzitako film laburrak ezagutaraztea da helburua. Taupa mugimenduak antolatzen du ekimena.

Pantailak Euskarazek eta Hizkuntz Eskubideen Behatokiak aurkeztu dituzte datu "kezkagarriak". Euskaraz eskaini diren estreinaldi kopurua ez dela %1,6ra iritsi ondorioztatu dute. Erakunde publikoei eskatu diete "herritar guztien hizkuntza eskubideak" zinemetan ere... [+]

Geroz eta ekoizpen gehiagok baliatzen dituzte teknologia berriak, izan plano orokor eta jendetsuak figurante bidez egitea aurrezteko, izan efektu bereziak are azkarrago egiteko. Azken urtean, dena den, Euskal Herriko zine-aretoak gehien bete dituztenetako bi pelikulek adimen... [+]

Otsailaren 24tik eta martxoaren 1era bitartean, astebetez 60 lan proiektatuko dituzte Punto de Vista zinema dokumentalaren jaialdian. Hamar film luze eta zazpi labur lehiatuko dira Sail Ofizialean; tartean mundu mailako lau estreinaldi eta Maddi Barber eta Marina Lameiro... [+]

A conference for architects has just been held in Madrid to discuss the crisis of the professional architect. They have distinguished the traditional and contemporary way of being an architect. What is traditional? From the epic architect who appears in The Brutalist, where... [+]

Itoiz, udako sesioak filma estreinatu dute zinema aretoetan. Juan Carlos Perez taldekidearen hitz eta doinuak biltzen ditu Larraitz Zuazo, Zuri Goikoetxea eta Ainhoa Andrakaren filmak. Haiekin mintzatu gara Metropoli Foralean.