Allegations of torture of the accused in Burgos: in search of evidence to judge the Franco regime

- The war council held in Burgos in December 1970 against sixteen ETA militants marked a milestone in believing that there were alternatives beyond Franco. In that process, the testimonies of torture suffered by the defendants were fundamental to evidence the regime's oppression. The relatives who travelled to the Vatican wanted to make available to the Pope a report containing the torture they had suffered. Today, it's gone.

Burgos, December 1970. The Franco trial 16 revolutionary Vasco-speakers for a tremendous process, all of them of ETA. The Prosecutor emits 6 to death: IZKO, Uriarte, Onaindia, Larena, Gorostidi and Dorronsoro. We are on 3 December, the day before all Euskadi has entered the general strike, all the peoples of Spain join in the activities for the brothers. In the workplaces, in the factories, in the schools, in the streets… there are shouting against the dictatorship from anywhere.” Thus begins the introduction of the famous recording that has come to us from that Burgos war council, a significant display of red time at that time.

The trial was held between 3 and 9 December 1970, but the prosecutor had been conspiring for several months. In addition to the murder of torturing Commissioner Meliton Manzanas, ETA members were attributed more than a series of assaults and robberies, which were involved in a very brief process to give experience. We can say that the chain of repression narrowed in 1968, when the civil guards murdered Txabi Etxaberrieta in Bentaundi (Tolosa). Then came the murders of Manzanas and the raids of Bilbao Artekale and Mogrovejo of Cantabria against the leaders of ETA. In 1969, only 1,953 people were arrested by the police in Hego Euskal Herria, many of whom were tortured.

As we enter the exhibition that these days Aranzadi has mounted on the Campus of Gipuzkoa of the UPV/EHU in Donostia, in line with the Burgos Process, we can hear a historical audio in which the torn voice of Mario Onaindia shouts “Gora Euskadi Askatuta!” and the accused sing before the Coronel Sabak. It was one of the most significant moments in the anti-francoist struggle. But later in the exhibition, the batons and pliers that we can see in a messy conglomerate wooden table reflect that this struggle had more suffering than epic.

Pope Paul VI did not welcome the relatives of the defendants, but the public denunciation of the torture of the dossier served to undress the Franco regime around the world.

Even though we are now more aware of torture, it is surprising that the 1970s narrative does not have a wider place. Half a century ago, however, the defenses highlighted the practices of the accused at the police station as a sign of the cruelty of the Franco regime. Precisely, the relatives who had travelled to the Vatican several weeks before the trial also wanted to send Pope Paul VI, through a dossier, information on the torture they have suffered.

Defend yourself by attacking

Family members reported that self-incrimination was achieved through the practice of torture. But it was not the first time, of course, that the police used this type of method, nor will it be the last – the Basque Institute of Criminology has received 4,113 cases of torture between 1960 and 2014, carried out by the police, the Civil Guard and the Ertzaintza.

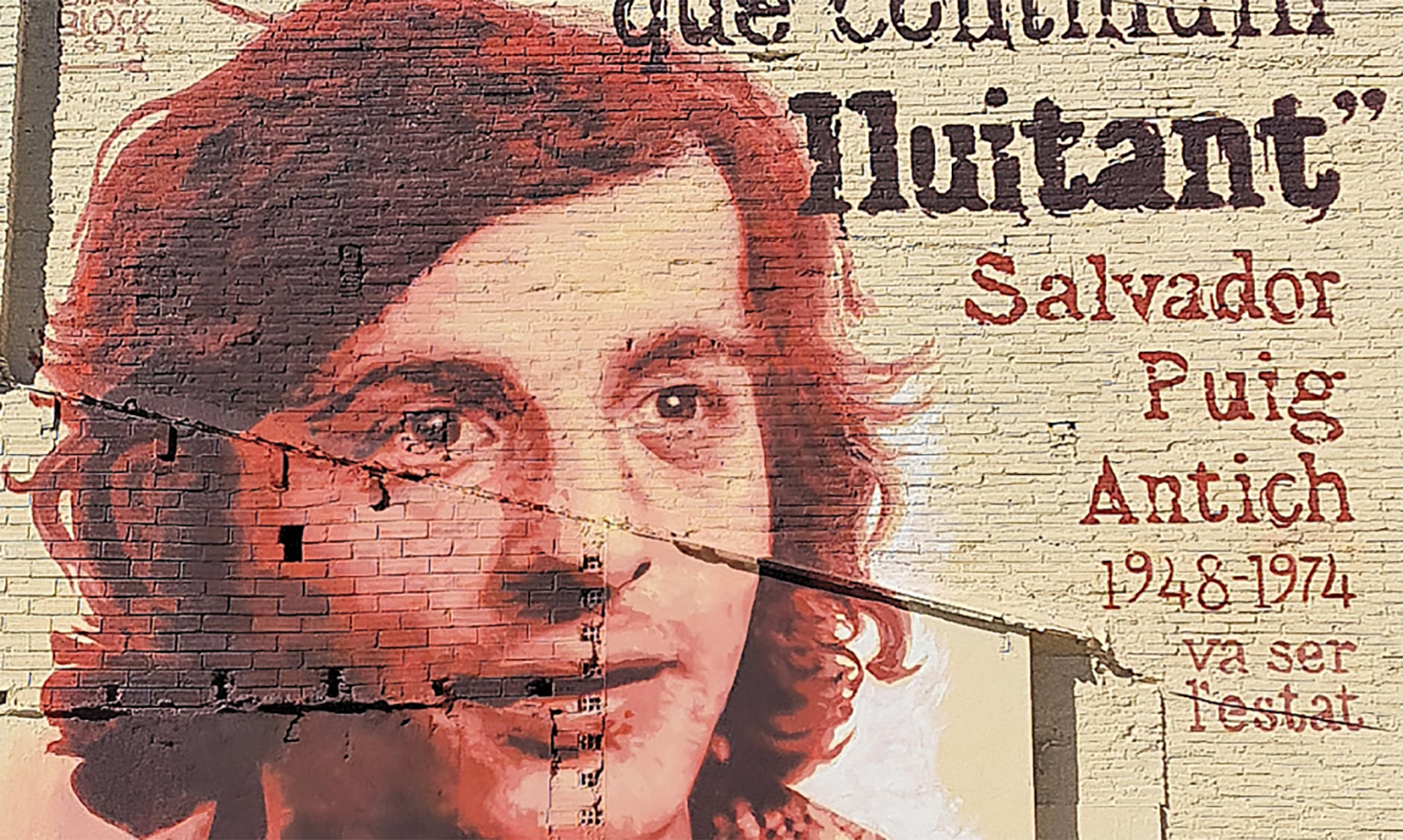

On 16 August 1968, shortly after the death of Manzanas, the Franco Government again promulgated the Law on the Suppression of Terrorism and the Post-War Banditry. Subsequently, the cases related to ETA began to be tried in the War Councils under a "simple and firm" military law, according to a letter stating that the defense lawyers of the defendants in Burgos, Miguel Castells, Pedro Ibarra and Francisco Letamendia, were lawyers for the anniversary: “Any criticism and opposition to the regime was condemned.” But on the contrary, through a clear strategy, “the defendants defend themselves in the Hall of Justice by attacking,” the courts managed to get Franco to be tried, leaving their oppression in the eyes of the whole world.

The recently deceased journalist Gisèle Halimi followed the trial live and published it in the book Le procès de Burgos (The Burgos Process) with mastery, among other things, the torture of the defendants: “They put me on what they called the operating table. They took me by my hands and legs, closed my mouth with papers and beat me to death, especially in my chest and legs,” Jone Dorronsoro told the jury.

.jpg)

This was not the first time they were told in a “judgment of rupture.” Two years earlier, in 1968, accused of incentivizing the house of the Francoist mayor of Lazkao, several defendants also tried to give their testimony; his lawyer, Castells, explained what happened to this media (Larrun, nº 82. ): "They were harsh demonstrations and one of them entered inside the barracks. Torture was denounced at that war council for the first time. We asked the prisoner how he reported the torture, the military judge withdrew his word, we protested...”

Since then, the War Councils have been transferred outside Euskal Herria. Why, then, did the Burgos study in December 1970 become particularly important? Among other things, because of the international impact through mobilizations and the press.

Travel to the Vatican

San Juan de Luz, Autumn 1970. Relatives of the accused have met Juan Mari Arrangi and Telesforo Monzón, who want to be with the Pope and have not been able to attend. Arrangi is exiled for helping to escape an ETA member, as he had previously made another trip to Rome on the occasion of the imprisonment of the Basque priests at the Derio seminary: “The relatives went to the Vatican to ask for justice, not mercy, as Paulo intended VI.ak,” says the priest and current collaborator of ARGIA.

A few weeks later, on 10 November, thanks to the work carried out with various intermediaries, including the Jesuit José María Díez Alegría and the poet Rafael Alberti, the mothers and sisters of the defendants manage to reach the door of the Vatican Secretary of State, accompanied by Arrangi. No further. A letter to the Pope, through Monsignor Giovanni Benelli, the then Secretary of State: “We want the Church to take over. (…) Our sons and daughters are at risk of being sentenced to death and the evidence for such a possible sentence is based on statements obtained under torture,” the typed text states.

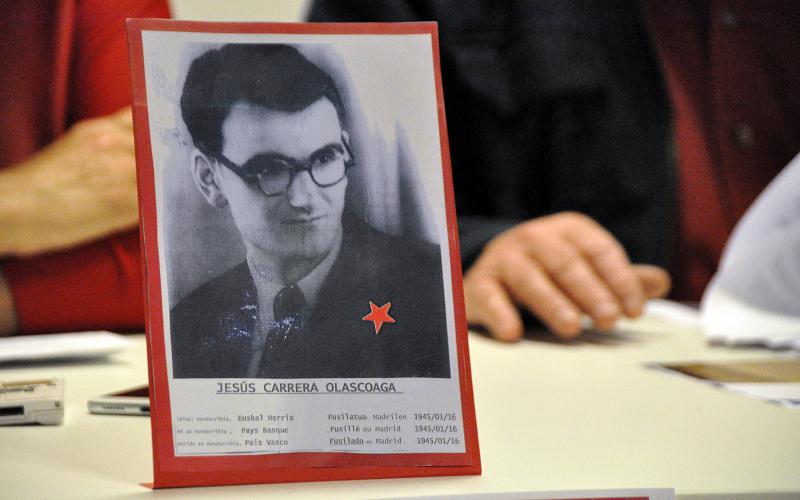

Along with this, they have a complete dossier produced by Arrangi, with the information submitted by lawyers Juan Mari Bandrés and José Antonio Etxebarrieta, brother of Txabi Etxabarrieta, and statements with the signing of the defendants, explaining the torture suffered, complemented by the famous drawings of torture previously made by Xabier Zumalde El Cabra.

Paulo VI.ak has received the documentation, but will not receive his relatives, as he appears to be pressured by the Spanish Embassy. In return, it offers some rosaries to those who have gone to Rome, who, of course, will not accept the gift. Justice, not mercy.

Also in the hands of Franco

The removal of the rosaries was rapidly extended by international means, as well as the reasons for the travel of family members and the allegations of torture, especially in those of Italy: “All Basque prisoners to be tried have been tortured,” said Paese Sera newspaper; “Bureau of operations: declarations obtained through torture”, Communist journalists L’Unità… The Vatican press officer had to justify Paulo’s position VI.aren saying that they went to ask for their opinion on the “political situation” of Euskal Herria.

However, those roles that torture had proved to have taken a longer route. “Paulo VI.ak closed the door in the morning, while in the afternoon the Black Pope, the head of the Jesuits, Pedro Arrupe, received us,” Arrangi explains. He promised us to put the dossier in the hands of the dictator Franco personally. And I know that a few days before the Burgos trial he went to Madrid and fulfilled his promise.”

Where is the report?

The trail of the historic document explaining the torture has been lost, which has to do with the prison that Arrangi suffered upon his return from exile. It is possible that the valuable test used by the international community to judge Franco is at the Jesuit Grand House, but the Arrupe Fund is closed for now. Nor does it appear in the documents of the Basque Government, although the delegate of the lehendakari Leizaola in Rome, Ángel Ojanguren, collected a copy.

.jpg)

Finally, in the rich Benedictine archive of Lazkao we found the papers of our trip to the Vatican in 1970: Letters to the Pope, press reports prepared by Arrangi… but there are no pages on the torture suffered by the Burgans. There is another dossier with the well-known drawings of El Cabra, used for years to represent torture, until in 1976 ARGIA published photographs of the bruised body of Anparo Arango, and testimonies of several detainees in 1969; on the contrary, a brief final statement says that those who were still “incommunicado” are missing.

In any case, the public denunciation of torture served to undress Francoism around the world. As a result of the protests surrounding the Burgos Process, the Franco regime withdrew for the first time – beyond the strong competition between the “technocrats” of the government controlled by Opus Dei and the “bunker” formed by the military. On 28 December 1970, the sentence was released: nine death sentences and 519 years ' imprisonment for defendants, more than requested by the prosecutor. Two days later, the general captain of Burgos, Tomás García Rebull, confirmed the convictions, but within a few hours, at the request of the Council of Ministers, Franco decided to commute the death sentences: “With a great patriotism, I judge it,” the dictator said, although everyone knew that he had been judged himself.

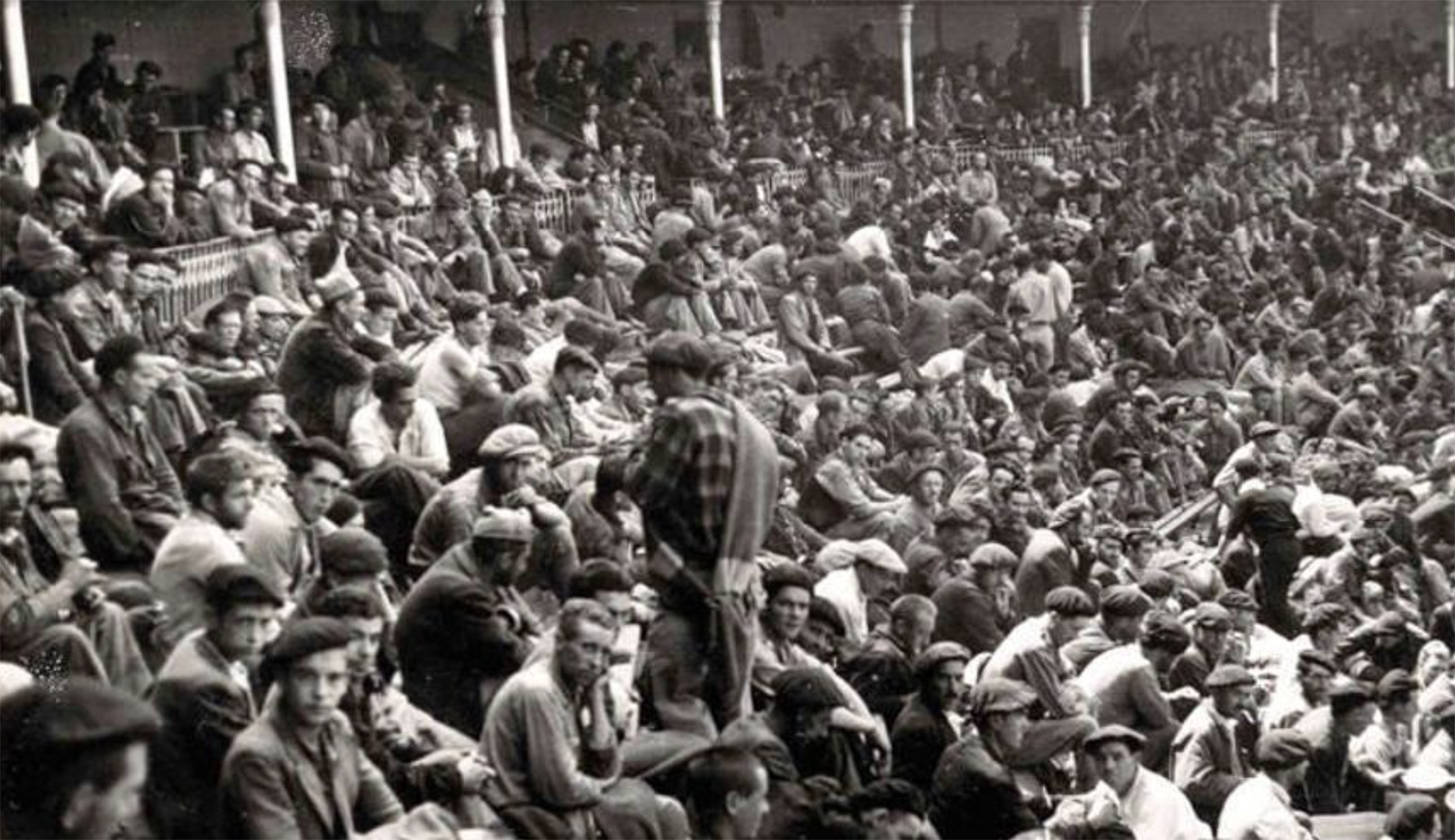

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]