Association that the cider of Ipar Euskal Herria has risen

- The association that has resumed its activity in Ipar Euskal Herria, Sagartza, celebrates 30 years in 2020. It has identified over a hundred varieties of native apples, replanting them in private and public areas so that the future can be secured. Seven of them by default have created the Eztigar Dei cooperative and about thirty cider producers are making cider.

We got going very simply,” recalls Pantxika Maitia, one of the founders of Sagartza. We started with simplicity and moved in the same way, doing a huge amount of work since 1990. The Sagartza association, which has resurrected the Sidrera activity in Ipar Euskal Herria, celebrates 30 years in 2020.

“There were no apples anymore, there were many missing guys,” Maitia recalls, looking at the 90s. Until then, however, the lands of Lapurdi, Nafarroa Beherea and Zuberoa had been filled with apples. It was a great variety: able to eat apples and drink cider throughout the year and satisfy all tastes. But the day after World War II, the modernization of agriculture began and apples were plucked out to channel more space to the machines. Although some trees remained standing, knowledge of the graft of them was lost. From generation to generation, the secular science chain was broken: “They learned to use machines and lost knowledge of insertion,” says Gabriel Durruti, a member of the association.

Of course, the modernisation of mountain crops did not allow for an increase in income and, in general, the farms were in a critical economic situation. In this context, the creation of Sagartze is framed. The idea of planting apples emerged in a meeting organized by the Hemen Association, which works to promote the economic development of Ipar Euskal Herria. More specifically, in a public plenary session held in Izpura in 1989, consideration was given to the possibilities of living and working in the Basque Country. “As we pondered what the new entrances of money for small farms could be, one of them replied “apples, apples, apples!”

This idea soon reached the ears of Durruti, the puff who was passionate about fruit. Great objectives, motivation and militant and passionate people. You can do great things if you have those three components. Suppose that some thirty farmers or owners joined the project and between 1994 and 1996 planted 16,000 blocks inside Ipar Euskal Herria. They spent the first four years looking for apples, choosing seven types for the project: Anisa or Apez Sagarra, Eri Sagarra, Gordin Xuria, Mamula, Pedestrixa, Ondomotxa and Eztika.

COLLECTIVELY FROM THE BEGINNING

They have been inherent in the collective character since its inception. Reflection and action, all in group. The Eztigar cooperative, established in November 1996, was responsible for the production and marketing of cider and juice (producers sell directly part of the production). They are also part of the Arrapitz Federation, formed by structures working for sustainable agriculture. “We want others to learn from what others know and learn from ours, always collectively.”

Maitia says that they also “collaborate” with apple producers from Hego Euskal Herria. Many invitations have been obtained for research, the opening of the Txox and reflection meetings. “We could do much more, because there is a lot of interest on both sides.” For example, apples from Gipuzkoa have been purchased to see if they adapt to the territory of Ipar Euskal Herria.

APPLES IDENTIFICATION

The Eztigar cooperative, in its professional aspect, is responsible for the capture, identification and classification of apples. Through Lapurdi, Nafarroa Beherea and Zuberoa, Maitia says there is an “incredible treasure.” At the moment, about 130 varieties of apples have been identified. Their conservative apples can be found at the Hazparne Agriculture School, at the Garro de Lekorne, in the Maule Ageria area and in Irabarne. They know they're just at the beginning, because they know they're more than several classes. Why? Because most of the territory of Ipar Euskal Herria is still to be explored. “We want to do that work by heart.” In addition, a thousand trees are planted each year in the house of a private individual or in the consecrations of Eztigar. Training days are also being organised so that, among other things, knowledge of the vaccination they need is transferred.

LOOKING AT THE NEW GENERATION

Sagartze is experiencing the difficulties of the associative world. Involvement on the one hand. Because even if they have colleagues, the daily work is in the hands of a yawn. With age, you look at the next generation. They would like young people to enter society. They know that, for the time being, this succession is not guaranteed: “We create the partnership, so it’s a pleasure to be there. However, it’s harder to get involved in something others have created,” says Maitia. In any case, even if they were willing to give in to the witness, they would want them to continue with the values they have.

They also look at consecrations. Those who planted apples after 30 years are either portrayed or nearby. The big challenge of the succession of farms is there: “We have to secure the cooperative’s offer, we need 300 tons of apples.” They will soon begin a phase of reflection to reflect on all this and find solutions.

They do, they look to the future, with a thousand ideas in their heads. Although modest, Maitia confesses that: “30 years we have never said it… but I will say it: we can be proud of what we have done.”

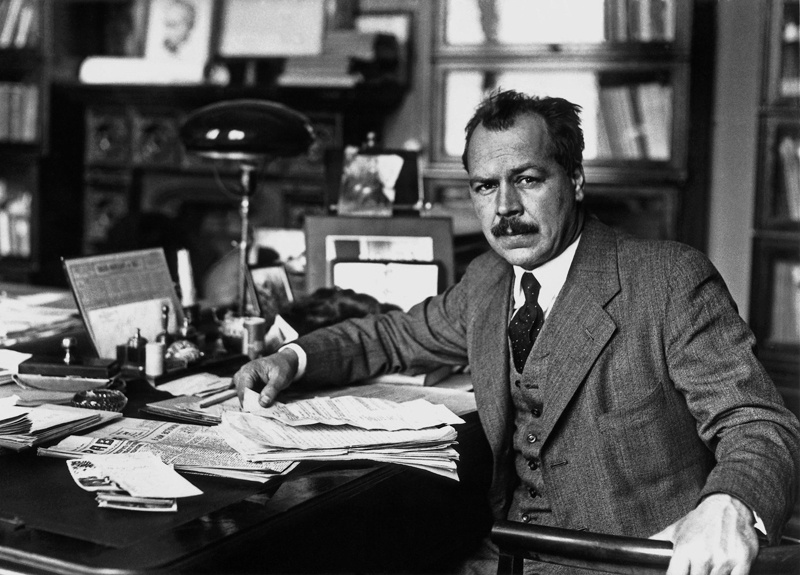

Gabriel Durruti, one of the founders of the Sagartza association

"It's the apples here that adapt to the earth and to the time here."

.jpg)

It is hard to imagine Sagartze’s work without the work done by Gabriel Durruti, his partner. He is well aware of the 1989 Izpura meeting, in which he found young people drawn to cider, whom he did not know at the time. It didn't take long to realize they had little science and experience, but a lot of will. It was then that he took on the task of searching and grafting the different types of apples. Since then he has been in it, eager to follow it as long as possible. Because cider is a real passion.

How did you relate to finding apples?

The Sagarduk started with three types: Eztika, Pedestrixa and Anisa. I told them as a hazpacho that the king of Hazparne's cider was Mamula. We had to put the mammal and many others in the same force, because if there's an illness or a bad genius, it takes plurality to move forward. We didn't have pulp anymore, we didn't. So I started to see apples at the ends of the lost fields and neighborhoods of Euskal Herria.

It's also a job of classification.

To do this, you need to know how to do it, know the classification rules and apples. You also need the memory of Christ and the ability to criticize yourself because it advances by mistake and by resumption. For example, even if it is the same class, two plants can apparently produce two different apples, all green on the North and yellow on the trepadora. It's a great job to know. Analytical research is also carried out. In the apples of the Basque Country we have 80% salads or acids and 20% sweets. The Basques love that acidity, both in apples and cider.

How many classes do you have intercepted?

In the interior of the continental Basque Country I have detected about 70 types of species considered here (Garazi, Hazparne, Larzabale, Heleta and the surrounding area of Bidarrai). I've confined myself to these places by choice.

Why?

I didn't go where the railroad came, thinking the market was coming from the outside. I'm not saying they're not ancient species, I mean they're probably not autochthonous. Bidarrai had no market, no railways, that is, no one had arrived and the apples were witnesses. The market also makes the type, apples are produced based on the cider that people love. I haven't gone to look for apples from the coast, because they're not the same as the ones inside. Age also makes the guy.

The importance of the local.

I have confined myself to areas protected by the west wind. For example, I did not go to the campas of Donapaleu either, because they do not have the same time as the apples of the mountain. The apples on the coast are in a special time, if you take one from there and bring it to Hazparne it is not said to be OK. The principle is clear: it is the apples from here that adapt to the earth and to the time of here. If you have to make money, you have to go through these. It's not good to take what gives you the most, but you have to try, so we threw ourselves into a wall.

It has extended the area to Zuberoa.

They have come to ask us for help. I told them that I would do the work, but under two conditions: that I would integrate the classes I was bringing and we would plant them in Maule. It's not that we don't want exchanges, but the apples that are good at Zuberoa are from Zuberoa. I will finish the one there and perhaps I will go to Urruña, Sara and San Juan de Luz.

You also look at the DNA of the apple.

We talked to the National Institute for Agri-Economic Research (INRA). They look at DNA and compare it to 6,000 other types in France. At first we've sent you 50 types. It has appeared that we have about twenty-five whole here, which so far no one knew. There are a dozen names that were picked up by INRA or the conservatories in Euskera. For example, the so-called Min Xuria is Tchuy. Here are some classes above France. The sound of Michelotte and our sound of honey appears at the end as the same. So where does it go? We would need a lifetime to respond to that. We've also sent 50 types of Zuberoa. There it will appear if the outside came in with the train.

You have partners in the collections.

The first was completed in 1990, at the Hazparne School of Agriculture. We planted 35 classes from three to three. The second collection, about ten years ago, is on the lap of the Garroa Castle of Lekorne. We have about 80 guys here. We also have the collection in Zuberoa, one in the public space Mauleko Ageria and another in Irabarne, planted five years ago, with 47 types. Now we have to occupy a place to plant others. We are not there forever and an institution should take over the succession of those collections. We need a genuine conservatory.