No beer without work

- USA, 30 June 1919. The Alcohol War Prohibition Act entered into force and, the following day, the sale of alcoholic beverages with a graduation of over 1.28 per cent throughout the country was banned.

June is not 31 days old, but on the first of July 1919 they would call him “Thirsty-First”, that is, the first day on which he was thirsty, playing with the word thirty-first (thirty-first).

The 18th amendment, known as the Dry Law, was proposed by the U.S. Senate a year earlier, on November 18, 1917. When 36 States were adopted in January 1919, it was incorporated into the Constitution. Finally, the Dry Law officially entered into force on 17 January 1920. But the law of 30 June was the first practical step in banning, and so the anti-ban movement focused on that date.

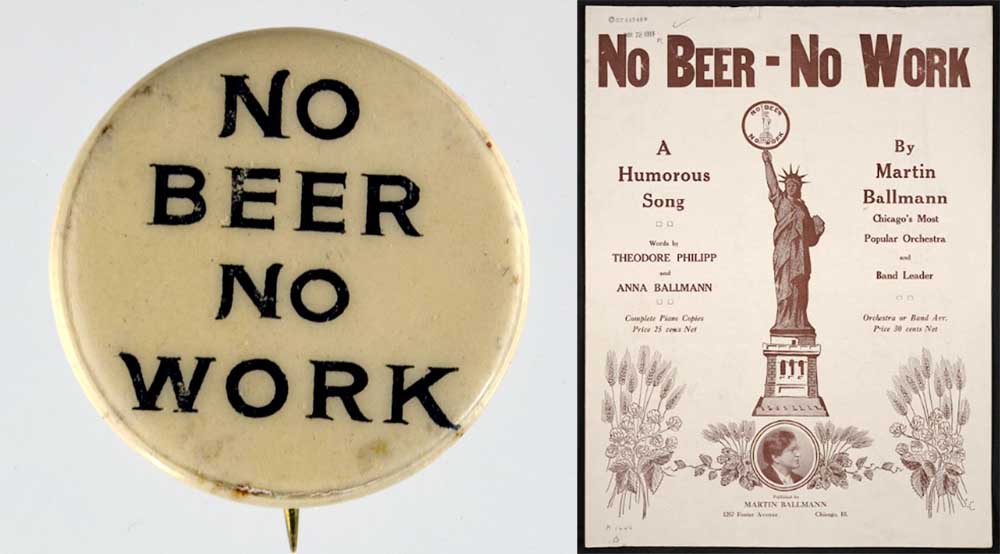

The movement started in New York and New Jersey under the slogan No beer no work (no beer no work). Union representatives began using badges with that slogan and also composed three songs with the title of the phrase. But the most important action of the movement would be the strike called for on 1 July. In the winter of 1919, the press announced the movement that was growing. Chicago’s The Evening World newspaper selected in its 9 February edition the headline “The No Beer No Work Movement has spread across the nation,” in which some 200,000 trade union delegates voted for the strike on July 1. In April, the Australian newspaper Northern Territory Times and Gazette reported that the day of the general strike announced that workers across the country were going to leave their jobs to order beer. And he picked up the words of the representative of the Central Federal Union, Ernest Bohn. “The force of the protest will force the Supreme Court to declare the amendment unconstitutional.”

But the protest had no effect. At least the newspapers at the beginning of July had not picked up anything similar, with a few exceptions. One of them said that on 9 July the bars in Allentown, Pennsylvania, had carried out a strike to alert the “horrors” of the ban. But, of course, they were not enough to satisfy the workers' thirst for beer in the coming years.