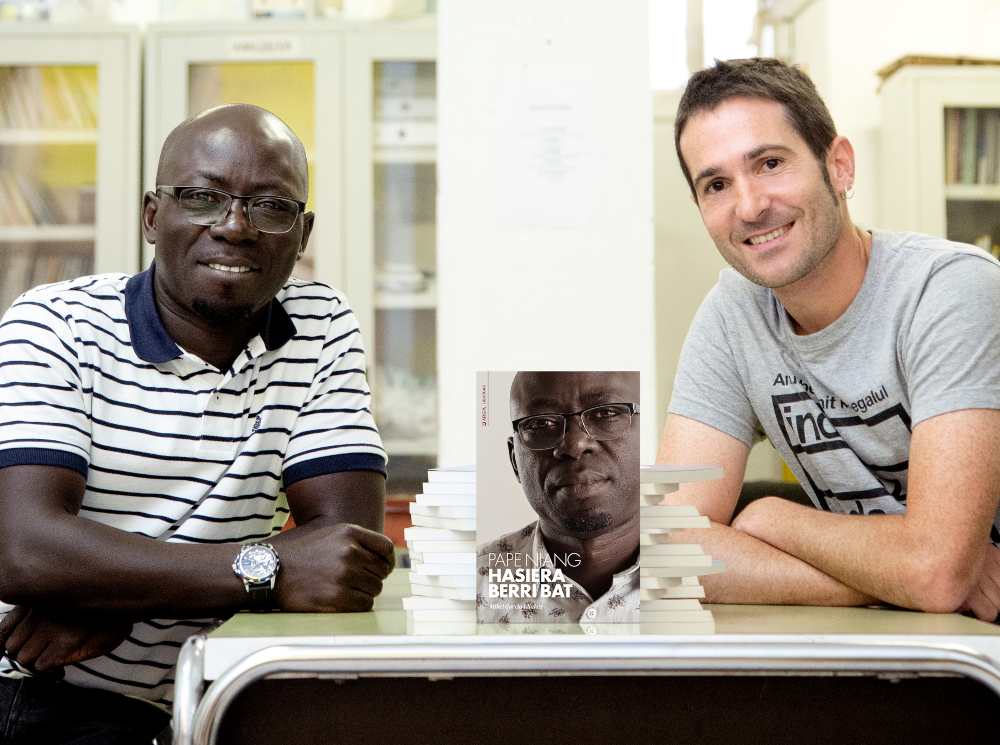

- ARGIA journalist Mikel García Idiakez addressed the Biscay capital in April 2018 with the aim of publicizing the situation of Senegalese traders. This was the first contact of the Senegalese merchants association Mbolo Moye Doole and ARGIA, the starting point of a fruitful collaborative road. On that road, the journalist meets Pape Niang, a migrant who left Senegal eleven years ago and turned to Europe. Pape Niang gathers her story: A new beginning in the book.

I'll ask you, Michael, first, and then you, Pape. How did you know you?

Mikel Garcia: In 2018 I came to Bilbao to make a report about the street vendors from Senegal for ARGIA. In addition to exposing the conditions in which they lived, it was intended to publicize the unjust law that would condemn the Senegalese, who had previously paid and exercised legally, to secrecy and legality. We came to know the situation and then we started to collaborate and meet with the Mbolo association in Bilbao. Pape was his president.

How did the idea of creating a book come about?

García: Knowing the injustice suffered by the Mbolo in the sale of streets, we saw that there was a way to turn the cry of Nobody is illegal into a project that strengthens both Mbolo and ARGIA. In collaboration, we launched the project and pulled out the Inor ez da ilegala T-shirts, in Basque and Wolof. The aim was to make this cry known and to support both projects with the money that would be obtained from it. That being the starting point, we've taken new steps: we made bags and the idea of the book came out as a natural step. With the book we strengthen the project and, in particular, we devote some of the benefits we have gained to the publication of the Wolof version of the book. The objective is to distribute the book free of charge among the migrants who arrive in the Basque Country so that they know the reality they will find. Among other things, the book includes a list of resources so that the migrant who has just arrived in Euskal Herria knows which door he can call.

Why has Pape been elected to testify?

García: Because paper is a life worth knowing, and there is also a reflection of what many migrants live. It has a very novel life, the book is easily read, and Pape has a lot to say. He raises many themes of reflection and debate, and through his life story he offers his vision of the world and how it has evolved as a consequence of the migratory process. I think it's a worldview that's worth reading and knowing.

What has the process been like?

García: We met every week at the headquarters of SOS Racism in Bilbao. They've always been very generous to us, we've felt this space very ours, we've been able to speak quietly. Pape and I have had more conversations than dialogues. We have spoken, reflected, debated and reflected on this and the other. I've known his life and I've received the notes, and then I've taken everything to paper.

Mikel Garcia Idiakez: "Pape has a very novel life, while raising many topics of reflection and debate in the book. As a result of the migratory process, he has been changing his vision of the world."

The book has an epilogue, arising from the need to collect the experience of a migrant woman.

García: This book narrates the life of the Papers and, as has already been said, reflects what many migrants live. At the same time, however, each migrant has its own migratory process, as there are very different realities, most of them very difficult. Paper is one of them, which is worth putting on the table, but is not responsible for all processes. So, even if I may just give a few strokes, I have had the need to reflect the reality of women migrating from Africa, to point out that many women also migrate and have added barriers. For this I have pulled from the information and documentation provided by Anaitz of the Irun Reception Network, because he has met many women who have carried out this migratory process.

Giving you, Pape, your face and your testimony can put you in a vulnerable situation, because you don't have papers. However, it has decided to take the step. Why?

Pape Niang: I don't have a disadvantage in my face or being arrested by the police tomorrow, I don't care, because I think what I'm doing works for something. If we tell what we live and suffer, maybe people understand what migration is. We also have to talk about the difficulties involved in migration: in order to imply that the migrant is always attentive to the police, to how to survive, seeking exits from the situation in which he lives. There are those who have a lot more people to tell, who could do what I'm doing, but maybe for all I've said, they're afraid.

The book also intends to be the testimony of migrants who have not been listened to or who have remained on the way. A single testimony has a double message: one for migrants and the other for whom we originate.

Niang: The important thing is the message. Anyone who has remained on the path of migration had much to count on, they were very experienced individuals for the simple fact of leaving their homeland. It is important to convey the message of all those people to tell them that if they left their country it was to survive. Not only do we have to say that many people have died in the Mediterranean, but we have to explain why those people have died in the attempt to lead their lives forward, thinking that their fate was better than their point of partida.Los migrants perceive us as a

zero on the left, without experience, as if we had no place of their own. Natives don't take into account that in our hometown, we're probably not that poor. Faced with this, migrants should value themselves, make us understand that we are people, make us understand that we live and work as here in our country of origin. And those who are native must realize that we immigrants deserve the same treatment as they do, they should strive to put ourselves on the skin. People there realize that immigrants are people, workers and responsible, and they're also very brave to make the way here. Crossing the desert with a five-liter bottle of water and a pack of cookies is not easy, people who have done so should be valued all over the world.

Those who think of migrating may also find it useful to pay attention to what you say. Because you say that what you will probably leave there is better than you can find in Europe.

Niang: We leave Africa because we have an idealized image of Europe, but when we come to it the reality is very different. People in Europe suffer more than in Africa. If you don't work in Europe, you don't eat, like in Africa, there's no such inequality. Television offers distorted images: As far as Africa is concerned, they teach you areas where people starve to death; as far as Europe is concerned, they offer pictures of incredible homes and roads. The images of Europe never show homeless people or people looking for food in the junk world. If young Africans see those images and migrants tell them that they live well here, they are encouraged to migrate. I'd say, don't come.

We have all the means to be able to work and live in Africa, what happens is that we have to reflect on how to organize them. We can't spend our whole lives migrating.

You say migration is a big business.

Niang: Yes, and the only one who loses out is the one who goes up to the kick. Those who stay with you, those who search for you, the traffickers, those who make it easy for you to kick... all those people benefit. The only one who loses is the migrant who gives him money to pay for it, and he may not even get to the other side of the Mediterranean. And if you get there, you know if you're going to get into the country. The Civil Guard can stop you and send you back to your country. If the difficulties are overcome, what is found is not easy either: you don’t understand your language, if you don’t have friends or acquaintances who welcome you at home it will cost you to get food… It’s complex.

It says that being a migrant is humiliating, more so if it's black.

Niang: Let me repeat until satiety: being a migrant is humiliating, let's not say if you're from the South of the Sahara. This is clearly seen in the job search, for example: if you're lucky enough to get a job, how is that job going to be? They may put you in the back of a restaurant, where nobody sees you, cleaning dishes; or working in the countryside, for 5 euros per hour. That's how I spoke last year, and I had a dispute with the boss. I was paying 5.5 euros an hour, and I was working nine hours a day, very hot and bearing the constant screams of the skipper. That's not work, it's losing your dignity. So I say it's humiliating to be a migrant. No matter how much you dream and your dotes, you're black and you're taken for black. A black man, nothing else. It's over.

Pape Niang: "Not only do we have to say that a lot of people have died in the Mediterranean, we have to explain the cause: these people have died in the attempt to lead their lives forward"

In the social economy, you have found the possible solution for migrants.

Niang: Yes, because migrants find it difficult to enter the labour market, it offers us an opportunity. I realized this when I learned about the experience of the Barcelona manteres: the migrants who were looking for a way out of their situation started a cooperative, and they were the ones who hired people who were in their situation, who had nothing. I really liked what I saw in Barcelona, that people who came with empty hands, like me, started a clothing and restaurant cooperative, encouraged me to do something similar. I really think it's an alternative. That is true, we find many difficulties along the way, administrative issues.

In fact, these difficulties have made the idea of your initial cooperative and the final idea different, right?

Niang: In fact, it is not that we have abandoned the idea of an initial cleaning cooperative, but another possibility has been put on the way: the agricultural cooperative. For the cleaning cooperative project, we seek Mikel's support. As the meetings passed and saw that the start-up process of the cooperative was blocked, Mikel told me: “Come to Artea to see what we are doing, we are creating a cooperative for migrants.” I went there, and he explained what they wanted to do and he taught me the estate. “Go there until you get started,” he invited me. So, since we have not even started the cleaning cooperative, we have entered there. If one day we manage to set up the cleaning cooperative, we can say that we have tried.

This agricultural cooperative has a very important social function for migrants.

Niang: As we agreed with Mikel de Artea, the cooperative is that the first year will accompany us in the process the members of the Artea network and help us with everything we need; little by little, we will take the cooperative on our own and they will be able to retire. At first we will be accompanied by the owner of the land, a man who knows a lot about agricultura.Como those who work in it are migrants, in the roles of the cooperative does not appear our name, although

those who work and decide on it are migrants. The objective is that, with employment and registration, papers should be obtained simultaneously.