"I had the support of being a professor, but not of most men."

- This year he has been awarded the Manuel Lekuona Award by Eusko Ikaskuntza. We thought we were going to resort to linguistics, to sociolinguistics and even to psychosociolinguistics, but as we went through ARGIA, we went to Zeruko Argia's times through unimaginable paths of escape memory, from past to present, with an exceptional guide.

Eusko Ikaskuntzaren Manuel Lekuona saria 2018. Irakasle eta ikerlaria. Filologia Erromanikoa ikasketak Madrilen egina, Beasaingo Lizeoko zuzendari zen 1968an. Ondoren, Deustuko Unibertsitatearen Donostiako EUTGn jardun zuen irakasle. 1983an EHUko Psikologia fakultatean hasi zen, 2011n erretiratu zen arte. Emakume aitzindari izan da ikastolako zuzendarietan, euskara dekanordeetan, katedradunetan eta Psikosoziolinguistikan. Donostiako Bagera Euskara Elkartearen omenaldia jasoa. ARGIA Zeruko Argia zen garaitik etxean pozik jasotzen duen MariaJose Azurmendiri, gure merezimendua.

[He starts questioning]...

In other times it was the Light of Heaven. My mother had always received him, and through him I got used to reading his magazine. I would say that from the 1950s on, we have the weekly at home. Before Celestial Light, now LIGHT. My father did nothing but work, and my mother told us what she read. Our mother was Bixenta Aierbe, of Segura, who at the age of 16 came to San Sebastian, at the house of the Intxausti, working in kitchen, sewing and embroidering... Born in the Philippines, Manuel Intxausti [Manila, 1900–Uztaritze, 1961] collaborated intensively after the 1936 war with the Abertzales, the children, the Basque Government and José Antonio Agirre who fled to the French Basque Country. How much money they would have given!

And your mother worked in her house.

Yes, in Donostia-San Sebastian, they had their house in Ondarreta. The house is still there. It used to be Intxausti. Now it has another name. My parents met in that house. My father was the driver of the house. When the war broke out, they went to Uztaritze, and later, I was several times with my parents in the house. And we were always given a story in Euskera. They were very special people.

In Ondarreta the house of the Intxausti, you also lived in the Old.

Yes ... And when I was young, I started the first school, at the age of 4-5, in the Handmaids of Jesus. You couldn't speak Basque, but I didn't know Spanish. They asked me, I understood in some way, but I wasn't able to answer. At that time, the slates were not glued to the wall, but had two sides, one facing the room and the other side of the back wall. They put me on the other side of the board. There I picked up the chalk and drew, and I loved drawing. I still do them.

[Today he does real paintings] I suffered a lot and I got rage. In addition, we lived in fear of speaking in Euskera, we didn't talk ... I started at the Sacred Heart College, and there were also people who knew Euskera quiet. Until after the course I did not know that some were speaking in Basque. So quietly, we started talking to each other in Basque, hidden from the nuns.

It's hard to believe.

And still today, the people who lived that then do as if they hadn't lived it. In social psychology, it's called "learned unprotection." Lack of protection learned. “What you said is not true! There was no ban here!” they say. They have accepted the lie. They live convinced that we invented things. On many occasions, instead of using war, empires have used other mechanisms to introduce certain beliefs within people, and not others. They change people's thinking. In the first, people oppose it, but they gradually accept it.

You mentioned cholera.

But fortunately, cholera doesn't last forever. In my life, I've had other stages. For example, when I went to Madrid to do the specialty of Romanesque Philology. There, I was consolidated by Euskera and Vasquism. There was a very large group of Euskaldunes in favour of the Basque country. They said that the Basque language was our language, that we had to speak in Basque, and they organized Basque classes. Some of us showed each other. On the one hand, I received classes to learn how to read and write, and on the other, I gave classes to those who knew less than I did. For example, my husband.

In 1963, you went to Madrid, at a time when there was no university in the Basque Country.

And if I wanted to study, I had to leave. There we were many Basques, about two hundred, mostly men. Women, a tenth or something. I was pushed by my mother, stimulated by the familiar atmosphere of the Intxausti to my mother. I had to study, and I learned a lot in Madrid. I studied Philology, but among other things, I attended classes and programs of history, literature, economics... I was very curious. And others did it like me. The first two years I did them in San Sebastian, the three of the specialty and another to do the doctorate, and I came to the Basque Country. In the same Madrid they offered me the work of a university professor, but I wanted here...

Four years in Madrid. And here, did you make a new Basque Country?

We tried. I was the first director of Beasain's Lyceum. I took that job because it was in Basque. I don't remember who and how they came to find me, but when I was in Madrid, I was coming to San Sebastian in the summer, and I joined the movement here, with Karmele Esnal. At that time, the ikastolas were starting to open and needed qualified teachers. They made me a director. How to teach, how to organize the ikastola itself, hire teachers... And that's where I struggled, because some people said that to be a teacher, you didn't need a degree.

Was it in conflict to be a graduate teacher?

Yes. And there was a huge struggle, especially in the third year, saying that I hired the teachers according to the title. But I was also caught because I had the title. At the time when many anti-systems had taken place, it was a rebellion: “The Spanish title to teach in Basque? No, sir!”... I, though, always tried to bring qualified teachers, until they kicked me out.

Did you get kicked?

Yes. I was sent the letter in Spanish. “Because of incompatibility with the other teachers,” they said. I managed to hire a few graduates, but there were more people out there who had no title. I was kicked out, and I have the spine: the ikastola, where the Basque is very strong, the Goierri... I have always been very dear Goierri, being my mother of Segura and my father of Legorreta! I'm starting to lose my memory, but "Because of differences with the other teachers," I'll never forget. I cried a lot, I was sad a lot. But they knew me at the University of the Jesuits [University of Deusto in San Sebastian, EUTG at one time], I had also given some classes in Beasain the last year I was, and I immediately started at the university.

After thirteen years of activity on the campus of San Sebastian at the University of Deusto, he worked in the faculty of Psychology of the recently released University of the Basque Country. Bilingualism has been one of the main research topics. Today we are talking about multilingualism.

We can be bilingual or multilingual, individual, but not social. In 1980, I was in Quebec, at the University of Laval, with William MacKey, [the most prestigious person in international sociolinguistics] and that's what he said. In the event that social bilingualism is possible, each language must have its own territorial scope and be the only official language in that territorial sphere. There is no more. In Canada, you have the French-speakers, you have the English-speakers. That's how they worked and they worked, as if they were Confederate states. MacKey was surprised, even though he was so crushed, by the force the Basque had among us. He said he hadn't seen anything like that in the world. And keep in mind that ours is a very complicated situation, divided into three administrative territories, into two states, which we have on top two hegemonic languages ... French was a true global language before World War I. MacKey said that we have never known balanced social bilingualism, a language needs its own territory. People can know one language, and two, and three, and a lot, but a particular territory needs a particular language. Society will work with one, not two.

In addition to MacKey, you have received another great sociolinguist at home: José Fishman.

Yes. We had it two or three times. Both are global experts, both concerned about the Basque process. Knowing how little we were, how we were divided, how we lost the war -- and yet, what strength we had to ignite it, or to resurrect it, both our language and the people themselves.

Turn on, don't turn on, we know Euskera, many. We speak Basque much less than the ones we know.

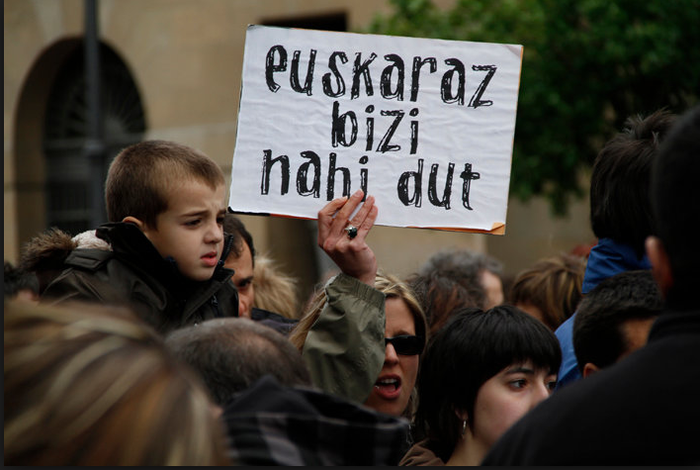

At one time we had a campaign in Donostia, “the first word in Basque”. We should now also get it going. Go to the store and in Spanish. Why? The merchant in front of us may well be able to speak in Basque. A few years ago I did it, I went to the Old Party, I entered the bar and I asked for Euskera. If you didn't answer in Euskera, goodbye! I was going to another one.

A militant!

And there are fewer and fewer Euskaldunes in the bars of the Old Part of Donostia. Back then, we went to the Old Party and we ate, we drank, we talked, we sang -- we did everything. Now, no. The first word we have to do in Euskera, everywhere you have to put someone who knows how to speak in Euskera, at least one.

I have referred to militancy, which has been awarded the Manuel Lekuona prize, because they have said that he is the scientist who has put the Basque country at the centre of his academic and militant career.

I was Vice-Dean of the Basque Country in the Faculty of Psychology and tried to put Vice-Dean of the Basque Country in other faculties of the university campus to take over the Basque Country. And we did. And we tried to normalize the language. In the 1980s, for example, we created a technical dictionary, we listed the terms we used in Spanish, we thought about how to tell it in Euskera, and we sent a proposal to Euskaltzaindia for advice. At first it was very difficult. Although the dean was Euskaldun, he did not have much sensitivity towards the Basque, so was his “learned helplessness”. He didn't leave, but he didn't dare to resist. He invented difficulties and difficulties. The work now done in Euskera at the university, the situation of the Basque country, has nothing to do with the work of yesteryear. Luckily.

Eusko Ikaskuntza has valued your leadership. Among other things, because you're one of the first women to become a professor at university. Has it helped you to be a woman?

I've had a nuisance! At my time, all of them were men, most of them in college. Everything was more difficult for us. You say that I am a professor, and that is true, but at that time men were given priority, even to be appointed as professors. In our faculty, I was the third professor. The first two were men. The third was also a man. I was the first female professor in the Faculty of Psychology. I had the support of being a professor, but not of most men. However, I had the largest and best resume. I have also experienced that situation.

The Manuel Lekuona Prize will please you bitterly!

I have husband and children and grandchildren, and thanks to them. If it hadn't been for me, if I hadn't been by my side helping me, I wouldn't have been able to move on. Or I wouldn't have done half.

“Euskaraz hitz egiteko esfortzua egin behar izaten dute batzuek. Nik, gaztelaniaz hitz egiteko egin behar izaten dut, eta frantsesez edo ingelesez egiteko ere bai. Ikasketak gaztelaniaz egin ditut txikitatik, eta horiek euskarara ekartzeko esfortzua egin behar izan dut. Nola esango nizuke, bada?”.

“Jakin genuen Euskaltzaindiak Arantzazun egindako bileran eztabaida izan zela, batzuk alde, beste batzuk kontra, baina nik erabakita neukan Euskaltzaindiak erabakiko zuena onartuko nuela, aurrera egingo nuela. Eta bide horretan saiatu nintzen Beasaingo Lizeoan zuzendari izan nintzen garaian”.

“Lehenik, ARGIAri eskerrak ematea dut. 1919an hasi eta orain arte egin duzuen lana miresgarria da. ‘Kazetaritza independentea. Informazioaren jabekuntza. Inongo partidu politikoren menpean egon gabe. Informazioa, bertakoa eta mundukoa’. Irakurleek ere esaten dute: ‘Beti euskararen eta euskal kulturaren alde’. Gainera, astekaria!... Nola ez dugu, bada, ARGIArekin bat eginda segituko!”.

We Basques move our feet behind the witness of Korrika to proclaim that we want to survive as a Basque people in favor of our language, with the aim of the Basque Country we desire.

The tipi-tapa is the first step taken by a migrant person who leaves his homeland in Africa,... [+]

Euskalgintzaren Kontseiluak eta Bizkaiko Foru Aldundiko langileak elkarretaratzea egin dute langileen egonkortzearen eta euskalduntzearen alde.

EH Bai koalizioak babesturiko Ahetzen zerrenda gailendu da bozen bigarren itzulian, joan den igandean, botoen %44 erdietsirik.

The victims created by the IAP are not only functionalized teachers thanks to the stabilization process brought about by the IAP Law, but much more. Some have been given some media visibility as a result of Steilas's appeal, but most of them are invisible. All the victims of the... [+]

.jpg)