"In Africa, you feel very white, you want and don't want to privilege."

- In twenty documentaries, it shows us the most terrible hells in the world. Now, he will offer a special about the Polish Ryszard Kapuściński, who witnessed the suffering of Africa like himself, at the San Sebastian Film Festival and will compete for the San Sebastian City Public Prize.

Kazetaria, zinema zuzendaria eta gidoigilea. Zinema dokumentalean egin du ibilbide nagusia. Lehen filma Nomadak Tx (2006) izan zen. 2014an Goya saria irabazi zuen Minerita lanarekin. 2015ean, dokumental labur onenarentzako Oscar saria jasotzeko hautagai izan zen Minerita. Donostiako Zinemaldian emango du Un día más con vida (Beste egun bat bizirik) Damian Nenow animatzaile poloniarrarekin batera. 1975ean, Angolan, Ryszard Kapuścińskiren bizipenak biltzen ditu, animazioa eta irudi errealak josiz.

What does the journalist do behind the camera?

When I was a kid, they gave me a photo machine and I tasted it. When I entered Communication School, I wasn't very clear about what I wanted to do, but as soon as I started the internship, I realized I wanted to be behind the camera. Others were looking to be in front of the camera, like good journalists, but I'd rather be behind. Maybe I had to study film, but well. I received more humanistic than technical training, and I do not regret it.

At the San Sebastian Film Festival you will present Ryszard Kapuściński, a paper about another journalist. What kind of movie is it?

It goes beyond the limits of the documentary. It's an animation film, a documentary image, but it crosses real images. We wanted to create a new language. I wanted to make one movie with two narrative genres. Not only did we want to make a documentary about Kapuściński, but we wanted to turn the viewer into his co-pilot during the Angolan war.

Why Kapuściński?

It's always marked me. I've read all of his books, and he encouraged me to travel to Africa. There has always been a kind of link between us. I have always been astonished. He's a writer, not a war journalist, and many say he's been the greatest chronicler of the 20th century. I was very poetic, very sensitive, I knew Africa very well. It's amazing how Angola's breakdown was told, when in 1975 it succeeded in separating itself from Portugal. It describes how the city of Luanda [capital of Angola] remains an empty skeleton when the settlers return to Portugal, how they carried all their things to the pier, in wooden boxes, to board ships… I have always imagined it as an animated graphic novel.

After the film Nomadak Tx, Pablo Iraburu, Harkaitz Martinez de San Vicente, Igor Otxoa and I went to festivals all over the world. After that, I was eager to make another feature film. I've been working for ten years, but he's finally here.

You premiered One more day alive at the Festival de Cannes. How are you?

It has been the best place for the premiere of this feature film that has lasted ten years. We compete in the official section and it has been historic. Public reception and criticism have been unbeatable. Thierry Fremaux, director of the festival, said something we really liked: “You won’t be the same person after watching this movie.” It was terrible to go there. The special Perlak section of the San Sebastian Film Festival will also be a surprise, as it collects some of the best films presented at other festivals.

On October 26, it will be premiered in theaters throughout the state and will be seen in film and television in many places around the world: In Portugal, the United Kingdom, Scandinavia, Poland, Belgium, Germany, China and in more than eleven places.

Meanwhile, you're still with documentaries, right?

Yes, of course. Love, a documentary on girls forced into prostitution in Sierra Leone, was released in April and now [at the end of August] I am going to Uganda to do work on refugees coming from Sudan. We have other things in Mozambique, in Sierra Leone ...

I love doing documentaries, but I also like to mix things with other formats. I'm a kind of fusion, maybe that's why. I've always been interested in Latin America, Africa -- and mix genres, like fiction and documentary, or animation and documentary, as in this case.

What has Nomadak Tx been in your career?

A wonderful start. It was my first job, and also a feature film. The idea was from Harkaitz and Igor of Oreka tx and producer Pablo Iraburu. They were clear about what they wanted to do and invited me to participate. The txalaparta is their lives and I was able to gather and capture the energy generated from them. It was amazing: the possibility of going with good friends, the way of traveling, only the txalaparta and the camera, the great freedom, with a lot of time and little money, with few ideas but very clear… They were magical journeys. The film's assembly was also difficult and enriching. A very organic process, very intense and with very good results. The film has won around twenty awards at the biggest festivals in history. That leaves you a mark. That's where you realize you want to do that kind of job.

Where did you go and what answer did you get?

We were recording in India, Morocco, Lapland, Mongolia -- people there would think we were crazy. The txalaparta is an instrument that draws attention, unknown, and that also emits a strong and strong sound. Harkaitz and Igor touch their whole body and that's also very striking. The txalaparta opens a lot of doors. In India we were particularly astonished by the children, but the following happened: they played in the country of the Samians when they came out of Mass and no one showed any interest. The truth is, 30 degrees below zero, and maybe that's also why.

How did the idea of making the documentary Minerita come about?

When I read the report that picks up Ander Izagirre's text and the photos of Dani Burgui, I felt the need to go there and meet Abigail, a mining girl. Cerro Rico, from Potosi (Bolivia), has been the hardest and hardest residency I've seen in my life, especially for women. They live in extreme permanent violence, because of their lifestyles and because they believe that mining men have the right to rape and beat them. I witnessed that grief and that suffering. Worst of all, these realities do not change easily. The only solution is to get out of there, but for them it is practically impossible. Total frustration. It was a very hard shoot in every way and, in addition, a coworker suffered an accident and was about to die. I became very excited.

Have you maintained the relationship with the Abigail, Ivonne and Lucia miners?

Yes. Abigail La Paz went to the capital to be a policeman, but returned to his mother's house on the hill. I didn't want to leave her alone. Ivonne is also there. In addition, one of the brothers suffered an accident and lost his arm and leg so he was taken to the hospital. The situation has worsened in recent years.

How does your suffering affect you?

I get it wrong every now and then, but I generally think I'm doing pretty well. In Sierra Leone it is very painful to see children in prison and prostituted girls in the street. These ideas I've hit during the nights in my brain. You can't help but think about those people, knowing that you can barely do anything.

He works for salesians and Medicus Mundi, among others.

I have had a very good relationship with the Salesians for ten years and we have already made so many other documentaries for them. We have great confidence and thanks to them I have been able to know terrible situations: These include children from Colombia, girls engaged in prostitution in Sierra Leone, girls accused of witchcraft in Togo, children on the streets of Angola and Haiti, and war refugees in Côte d'Ivoire. With Medicus Mundi we have made two documentaries in Mozambique, The Gold Rush and A Continuum.

Is it useful to disclose information about those hells to change things?

Yes. To change something first you have to know it. It has been a privilege for me to be able to give a voice to those people. I'm your speaker. I'm interested in people's stories of struggle to survive. It's very rewarding to see that your jobs are used to change some situations. After making the documentary Live, for example, the Government of Sierra Leone was aware of the work of the Salesians, applauded it, and has now begun to work to end the dramatic situation of child prostitution. It has been possible to reach and mobilise the agents with the capacity to change things. There's bleeding.

How do you work documentaries?

The documentation is the first. The more you prepare, the better. We do a lot of interviews before we go on Skype, for example. I have few but clear ideas. I'm an open person, and I like to meet people. Meet with simple people and listen to their stories. I admire those people. Seeing how they live, how they fight in different parts of the world, I don't feel pity, but admiration. They are the protagonists, the heroes in these documentaries, and that's how I feel good.

Is it easy to walk through those places with a camera?

In Africa, you feel very white and you feel in a state of involuntary privilege for being born in the first world. This privilege requires that all relationships be always unequal. Whatever you do, you can always go there, eat there every day and go home. I imagine that sometimes they will look at us with envy, especially because we can go where we want. Sometimes they also feel hatred.

After the earthquake, we went to Haiti to do some documentaries on the initiative of Donostia Alejandro Pacheco, who works at the UN. This is a very smart and very good person who wanted to make a documentary from a positive point of view to show his life stories. The Nomad saw Tx and liked it very much. In two months we made three nice films, but we had to endure pressures and insults. So many people have gone to look for creepy images, now there's a kind of hatred towards the target with the camera.

The issue of refugees and migrants is key.

Reality frightens me. Watching the newspaper makes you want to spit. We are seeing children in jail on the US border, separated from their parents; we drown hundreds of people at sea; xenophobic statements everywhere...

It is horrible, incomprehensible, selfish and miserable. How can the life of a person fleeing hell be crushed? And it's not just a question of politicians, it's a very widespread idea in society as well. I am proud to be Basque because here there is a lot of sensitivity, closeness and generosity, much greater than in other places. However, what is happening is terrible. As a society, it's a shame what we're doing.

What is your next job?

In addition to the documentary from Uganda, we have in our hands the project of a fictional feature film. Freetown is a story based on the situation of Pademba prison in the capital of Sierra Leone. More than 1,900 people, including many minors, are currently concentrated in prison, with a capacity of 300 people. They call this place "the hell of the earth," and what you see there is really hard. I've been three times, and he calls me screaming. That's the place that moved me the most, along with Cerro Rico.

Untzitin, bere etxean, hartu gaitu Donostiako Zinemaldirako azken lanaren emanaldiaren zain eta Ugandara beste dokumental bat grabatzera abiatu aurretik. Etxe eder eta koloretsuan bere 3 urteko umetxoaren jostailu eta marrazkiak nonahi. Kanaki Films ere Untzitin dago. Untziti Amaia Remirez ekoizlearekin batera sortu zuen ekoiztetxearen egoitzetako bat da (bestea Donostian dute). Biak aritzen dira lanean mundu zabalean dauden hamaika heroi xumeren historia latzak kontatzeko.

Itoiz, udako sesioak filma estreinatu dute zinema aretoetan. Juan Carlos Perez taldekidearen hitz eta doinuak biltzen ditu Larraitz Zuazo, Zuri Goikoetxea eta Ainhoa Andrakaren filmak. Haiekin mintzatu gara Metropoli Foralean.

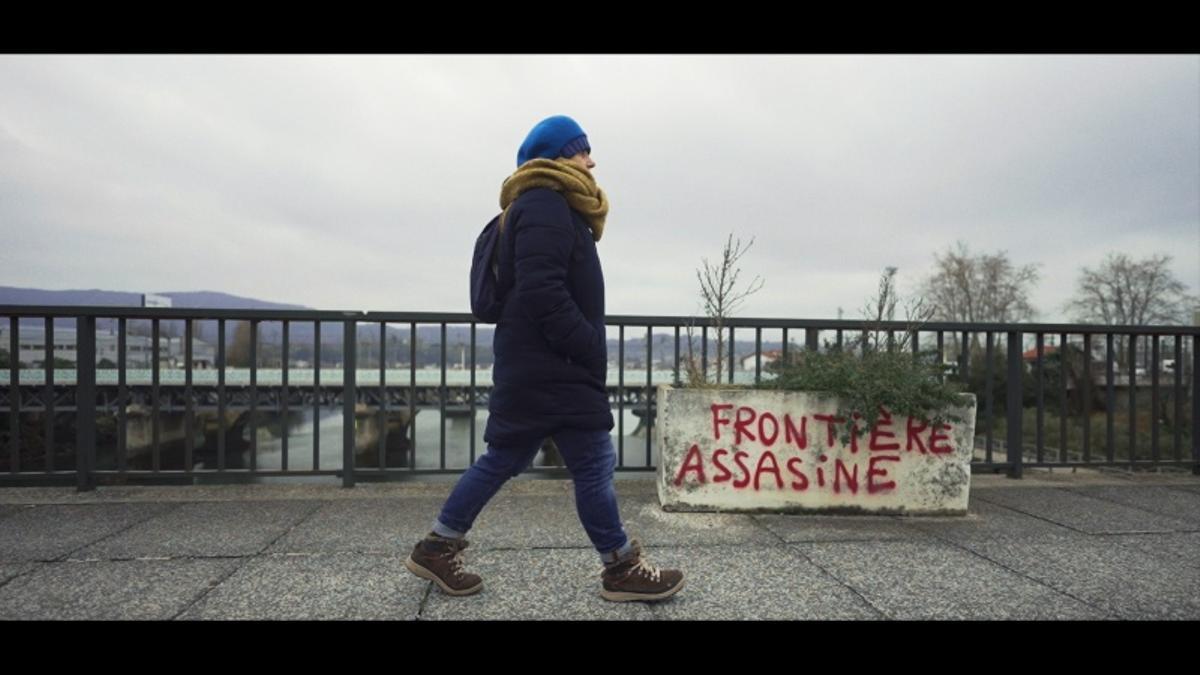

Projection of the documentary Bidasoa 2018-2023

Where: Martutene prison, Donostia

When: Friday, 22 December, 16:00h

Available as a network: Perfect on the platform

------------------------------------------------

It's Christmas. Friday after lunch. Let us go through the long... [+]

FIPADOC Nazioarteko dokumental jaialdia berriz heldu da Miarritzera. Urtarrilaren 19tik 27ra ospatuko dute, eta seigarren edizio honetan «Italia eta Afrika» izanen dira protagonistak.

Hands have a varied symbology. With hands the world is driven and with strong fists the command is supported. Power also fights with fists, picking fingers and raising hands up. Hands are necessary for those who have always been the losers of life, for that alone has been an... [+]

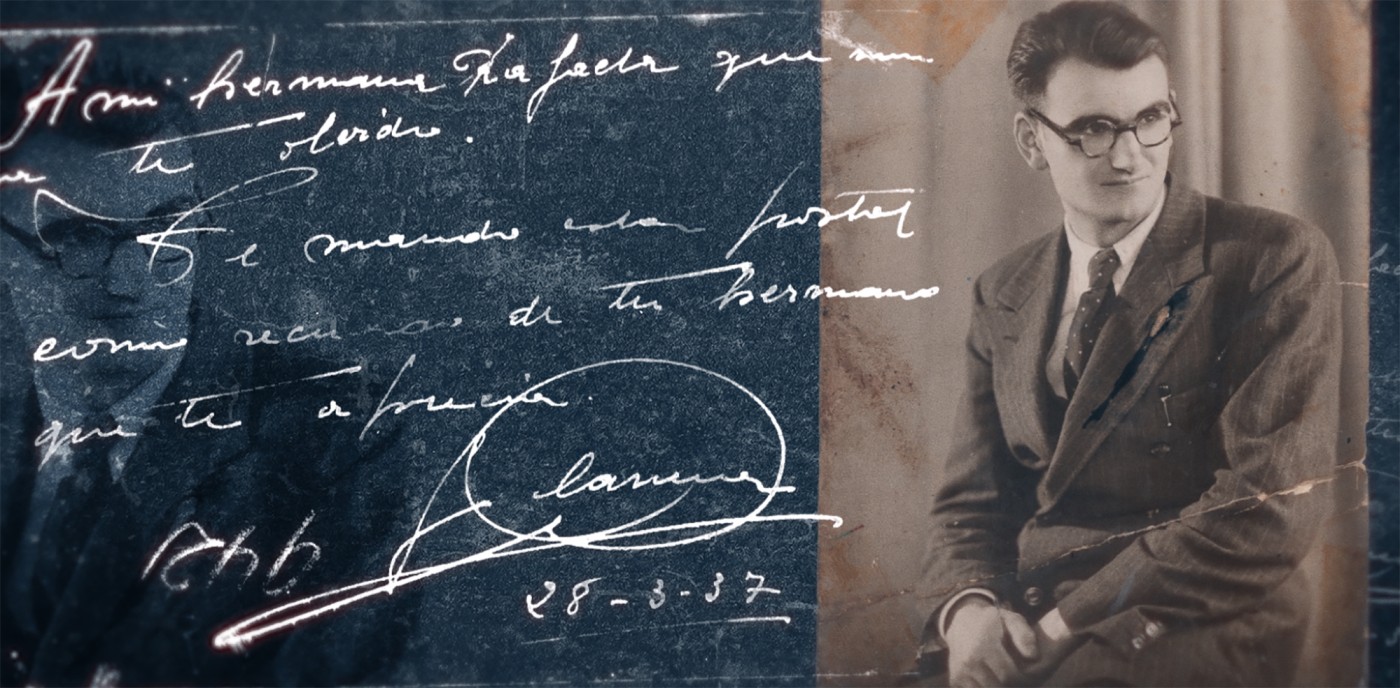

Lana finantzatzeko diru bilketa abiatu dute; ahalik eta gehien zabaldu nahi dute ikus-entzunezkoa, protagonistak sufritutakoa ezagutarazteko eta torturak salatzeko. Bi arnas kontatzen dira, torturaren eraginez itxi gabe dauden bi zauri: Sorzabalena eta haren ama Maria Nieves... [+]