A smile of solidarity and commitment

- On August 3, Pedro Berrioategortua Murgoitio died (Apatamonasterio, 1928 – Amorebieta-Etxano, 2018), a relentless wrestler who, during the Franco regime, faced the regime. When she handed out soft drinks with the truck, as when the Civil Guard harassed her, both in Derio’s confinement and in Zamora’s priestly prison, she never lost her grin of firmness.

“Those of us here today are well aware of the human condition of Periko Berrioategortua. He was a revolutionary exemplary in favour of the Basque working people, and that is why he suffered the misunderstandings, the arrests, the prison and the dirty war. It was always Basque, Basque, Independence, Socialist and Solidarity”.

These words were offered by his classmate and combat partner Juan Mari Arrangi at the civil farewell event held at Amorebieta-Etxano on 8 September. In addition to family members, the imprisoned prisoners Xabier Amuriza and Miren Amuriza, alias of Periko, their friend Juan Mari Areitio and former priest Juan Mari Zulaika, as well as representatives of the Abertzale Left and the association of prisoners and retaliation of the Goldat Franco regime came. One of the relatives sang with the guitar Txoria TXORI by Joxean Artze and Mikel Laboa, and in the documentary about the priestly prison of Zamora that is yet to be released they also read excerpts from the last interview of the abbot zornotzarra.

The son of the dwelling, from the moment the fountain was laid, was forced to change the Church inside and break the chains of the dictatorship. He began his work at the Abbey of Amorebieta-Etxano in 1960, when 339 Basque priests published their well-known letter. First fine, first warning. Berrioategortua decided to tread the same ground as simple people, either next to the strikers of the Bands, either creating consumer cooperatives – La Zornozana was one of the roots of Eroski – or working as a slave. The priest resigned from the state's pension and, like others, was forced to do so, to the surprise of the parishioners.

The year 1968 was special. The death of Txabi Etxebarrieta in Benta Berri (Tolosa) caused a shiver and showed that the regime would not respond with candor. The civilian governor banned funerals by the ETA militant and sent the people to the Civil Guard officers. Berrioategortua did not repent and the church of Amorebieta remained open. He was one and a half months in the priestly jail of Zamora; his bones then knew what the humble walls of the prison are. It wouldn't be the last time. He left his testimony at the priestly prison of Zamora (Txalaparta, 2011): a small patio that during the summer burned the sun and was terrible cold during the long winter showed them “the climatic cruelty that hid the prison of Madrid and the Vatican”.

According to Periko Berrioategortua, when they were in prison, they felt more weakness than strength, but that weakness “managed to gather”. In November 1968, the closing of Derio’s seminary was a collective empowerment among the Basque ecclesiastics, including him. For half a century, 80 priests claimed a poor, free, dynamic and indigenous Church through direct action. The threat of José María Cirarda was also entirely correct: “With all the weight of my authority I tell you that it would be very serious to sow the sin of discord,” he said as soon as the Francoist bishop became manager of the apostolic headquarters of Bilbao. The excuse of Concordia to deaf ears to Francoist repression and torture.

Berrioategortua suffered persecution on his own skin: he was taken from the motor, his car was burned, he was often arrested and given firewood. “Captain Hidalgo did what he wanted with me, in part,” recognized Miel A. Before the death of journalist Elustondo (Berria, 02-09-2018). Because Manuel Hidalgo Salas, the head of Gernika's civilian guards, was always in jail: “There is no one in Bizkaia who does not know Abate Berrio,” he once told one of the detainees.

In 1975, in a state of emergency, the clandestine newsletter Noticias del País Vasco began to be distributed during the state of emergency thanks to the support of many militants and committed citizens. Hidalgo believed that the editorial center of the magazine was in the Duranguesado, although it was in Madrid, and had in its sights the house Garage in the Astepe district of Amorebieta. There lived his partner Periko and Txaro Aranbarri, who had already left the Church, who died a year ago. This house of Astepe, besides being a source of information, was a support center for the priestly prisoners of Zamora, where the contribution of Aranbarri was essential.

After Franco's death, Berrioategortua immersed himself in the world of the press, participating and working on the creation of the Egin newspaper. In the last years of his life he focused on solidarity and commitment, on defending the rights of political prisoners, on the fight against the Boroa thermal power plant and on cooperation with numerous agents of the people, always with a smile in his mouth.

“During the last week at the hospital,” Juan Mari Arrangi explained in the farewell event, he was teaching his mobile phone to tell him that he was receiving many calls and messages from people concerned about his situation. And Perico always smiled with affection and gratitude.”

Kirola eta oroimena uztartuko dituzte, bigarrenez, mendi-martxa baten bitartez. Ez da lehiakorra izanen, helburua beste bat delako. La Fuga izeneko mendi martxak 1938ko sarraskia gogorarazi nahi du. Ezkabako gotorlekuan hasi eta Urepelen amaituko da. Maiatzaren 17an eginen dute.

Fusilamenduak, elektrodoak eta poltsa, hobi komunak, kolpismoa, jazarpena, drogak, Galindo, umiliazioak, gerra zikina, Intxaurrondo, narkotrafikoa, estoldak, hizkuntza inposaketa, Altsasu, inpunitatea… Guardia Zibilaren lorratza iluna da Euskal Herrian, baita Espainiako... [+]

Gogora Institutuak 1936ko Gerrako biktimen inguruan egindako txostenean "erreketeak, falangistak, Kondor Legioko hegazkinlari alemaniar naziak eta faxista italiarrak" ageri direla salatu du Intxorta 1937 elkarteak, eta izen horiek kentzeko eskatu du. Maria Jesus San Jose... [+]

Familiak eskatu bezala, aurten Angel oroitzeko ekitaldia lore-eskaintza txiki bat izan da, Martin Azpilikueta kalean oroitarazten duen plakaren ondoan. 21 urte geroago, Angel jada biktima-estatus ofizialarekin gogoratzen dute.

Bilbo Hari Gorria dinamikarekin ekarriko ditu gurera azken 150 urteetako Bilboko efemerideak Etxebarrieta Memoria Elkarteak. Iker Egiraun kideak xehetasunak eskaini dizkigu.

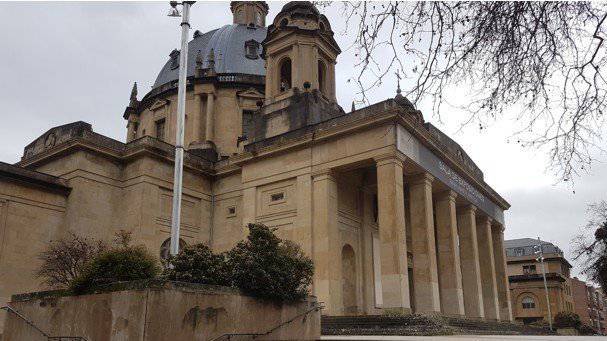

33/2013 Foru Legeari Xedapen gehigarri bat gehitu zaio datozen aldaketak gauzatu ahal izateko, eta horren bidez ahalbidetzen da “erregimen frankistaren garaipenaren gorespenezkoak gertatzen diren zati sinbolikoak erretiratzea eta kupularen barnealdeko margolanak... [+]

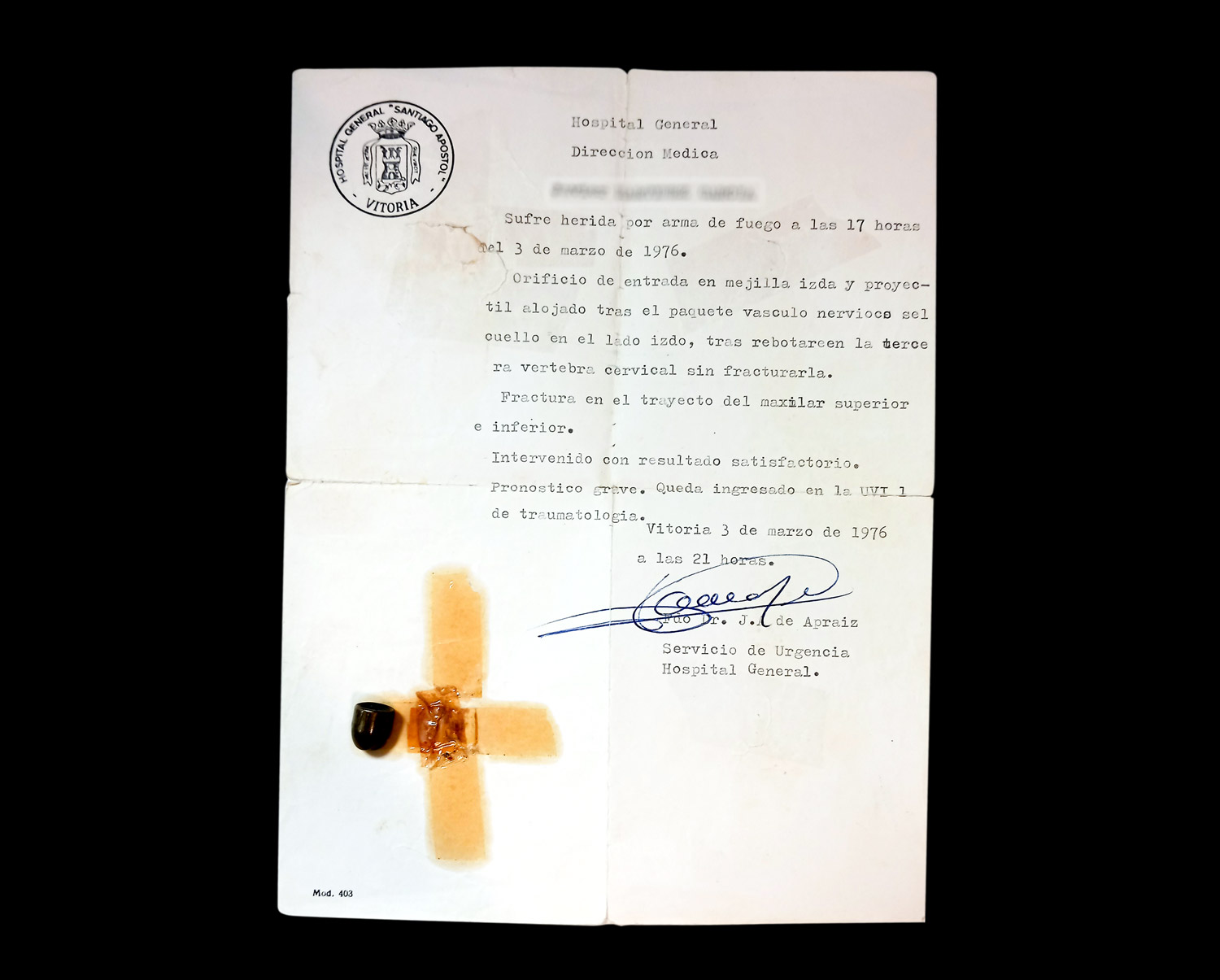

1976ko martxoaren 3an, Gasteizen, Poliziak ehunka tiro egin zituen asanbladan bildutako jendetzaren aurka, zabalduz eta erradikalizatuz zihoan greba mugimendua odoletan ito nahian. Bost langile hil zituzten, baina “egun hartan hildakoak gehiago ez izatea ia miraria... [+]

Memoria eta Bizikidetzako, Kanpo Ekintzako eta Euskarako Departamentuko Memoriaren Nafarroako Institutuak "Maistrak eta maisu errepresaliatuak Nafarroan (1936-1976)" hezkuntza-webgunea aurkeztu du.