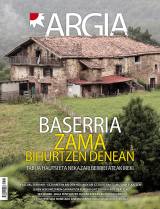

What will we do with the farmhouse?

- “When Grandma was little, she talked a lot about the last judgment, that the streets would be filled with shops and roads, the antichrist came and said that the world would end. I think he was referring to the end of the house. It was his way of saying that the dwelling was in danger.” It is told in the film Amama by Asier Altuna: if the caserío transmission is maintained, it is time to start talking.

Amama focuses on the conflict that the traditional rural world generates in today's society. This is how the protagonist's voice diffuses: “The dwelling will never be separated. By no means. It's the most sacred law of the farmhouse. The dwelling shall be entirely in the possession of a single child. Others will have to leave the farmhouse. Long ago, it was the eldest son who took the responsibility of staying at home. Today the heir is chosen.”

That is the question and that is the concern. Traditionally, to ensure the transmission of the dwelling, the eldest son of the house has remained, with the responsibility of cultivating the land and caring for his parents. Today, instead of choosing the only person who will give continuity to their work, the separation between several heirs has become commonplace. This is confirmed by the notary and professor at the University of Deusto, Andrés Urrutia. From Notaria it has been found that the dwelling was previously a complete economic unit and that nowadays it is becoming a dwelling of two or three families. And that, as far as its role to date is concerned, says that it is that of the disappearance of the dwelling. “It can be said that at one time the family was for the dwarf and that now, by losing that collective meaning, it is a dwarf for the owner”.

Maite Aristegi, former Secretary General of EHNE, Basque Agricultural Union, is currently working in the Rural Development Association of Debagoiena, moving the responsibilities of the transfer of the farmhouse. As Asier Altuna is from Bergara, and in the film he says: “Amama relates the work of the farmhouse with the hardness and we have to do work, but today we have to find other ways, new models, to keep the work of the farmhouse.” Aristegi shares with her brother the farmhouse and the cottage. It says that it is an opportunity that many have taken to ensure economic viability and that it has its risks: “Agrotourism emerged as a complement to the farmhouse, but on many occasions it has been done with it. If we do not work agriculture with tourism, the landscape and culture will be lost.”

Change of law in favour

Urrutia considers that the transfer of the dwelling is well organized from the point of view of legal remedies, it is only a problem: “What is at issue is the economic and cultural model of the farmhouse, we have moved to new and mechanized ways of managing empty dwellings and animals and land.” According to Urrutia, the transmission is legally guaranteed above all by the modification of the law, since in 2015 the Law of Basque Civil Law regulating successions in the Basque Country was approved.

When it comes to testing, the new law has lessened the obstacles. According to Aristegi, the best difference is that it expands the possibilities and leaves the hands "freer" to the owner of the dwelling. Before, the offspring inevitably had to be given four fifths or two thirds. Now, the legitimate (the share of each relative of the set of assets that parents have given to their children) has been reduced to a third and has left a larger amount for their free disposition. Similarly, the amount to be given to the offspring can now be distributed to the letter; it can leave everything to one and nothing to others. “Someone may think that leaving everything to one is not fair, but it must be understood that whoever takes the dwelling does so with the responsibility of cultivating the dwelling and the land. You don’t have to look at everything speculatively,” he stressed.

In the Basque Country there is an old concern for the integral maintenance of the farmhouse. As Aristegi explained to us, in this non-fragmentation effort different systems have been given in each territory: In Bizkaia, the trunk – inevitably the legacy of property inherited from its descendants – has been very important for its integral maintenance. In Gipuzkoa there has been no such thing, but Spanish civil law, and the loopholes of the law have been used not to divide it, as the figure of the stewardship”. Urrutia added that in Navarre the importance of the house has always been recognized, and that the new regulations have overcome the separation between the territories of Hegoalde. He explained that in Iparralde, over and above the distribution trend established by the French Civil Code, the landlords and notaries have maintained the estate in its entirety for long years, mainly through marriage contracts. However, he warned that in the same "there is a contrary trend".

Incommunication is one of the cross-cutting themes of the film Amama and, precisely, that is one of the main problems for Aristegi when the future of the farmhouse is questioned: there is no talk of the next day of the family farmhouse, at least until the beneficiary dies and the inheritance comes to the table. The successor pact, which includes the new law, is the instrument that allows us to speak before the death of the owner. Aristegi has been convinced that it is a step forward to give the voice that the owners of the farmhouse are alive.

Open doors

“If we want to stay alive to the fullest of all remaining farmhouses, we have to open them to people from outside,” says Aristegi. It tells of the joy that some neighbors have recently felt when selling and restarting the farmhouse: “It was a burden for them; they lived on the street and from time to time they had to go clean the dwelling and keep the land well. Now, they are glad to get it back on track. Basically, that’s what it’s all about, whether it’s sold, rented or in an agreement, to put the start up to value.” Because, as in some cases there are no relatives willing to give continuity to the dwelling, there are young people who want to approach the dwelling, but who do not have access to the land. Aristegi, on the other hand, is very suspicious and reluctant to go home to anyone other than his family: “If the one who doesn’t have to continue in the dwelling, because he has lived in the street or whatever, would like to have a corner to meet with the family, it is possible, there are a thousand possibilities; but if he doesn’t want to work the grounds, he should give a third party the opportunity to take advantage of them.”

Two years ago in Ipar Euskal Herria they created the ‘Zurkaitza’ transmission network, with the aim of strengthening ties between farmers who are willing to leave the farm and the young people who want to go to it.

Aristegi sees a need to reformulate the model for recruiting new people. Another experience has been set out as an example: “In the people themselves there are acquaintances that have been organized as common. Our cottages are very large and working together can be an opportunity to improve working conditions and enjoy holiday days, for example.” He warned that if the road to new opportunities is not made easier, there will soon be a great change.

In Iparralde they are underway

“In the north three houses are left, two new ones are placed. In the French state, where three are left, one is held alone. Culturally, the succession of the estate has a lot of strength here. However, the situation is negative: over the past 12 years we have lost about 1,100 homes.” According to Daniel Barberarena, a member of the Chamber of Agriculture of the Basque Country (EHLG), the data clearly demonstrate the situation.

“60% of farmers over 50 don’t know what they’re going to do with their farm, that’s the concern,” he says. A new phenomenon is that more and more people are approaching the villages outside the family; in general, the neighbours, both of the neighbouring peoples and of France. These were 7% of the houses in 2007 and today they account for about 20%. “They want to bind to the crop but they don’t have land or houses,” says the EHLG member.

Along the same lines as Aristegi, Barberá says that the biggest difficulty in talking about transmission is that it is taboo. “It’s a painful issue, because the succession of the farm is the succession of your ancestors, but if your ruins don’t want to take it? If you see the movie Amama, there's a rupture of the transmission rope, and that rupture brings a lot of suffering."

Aware of the need to create a dynamic, the EHLG organises in the autumn a fortnight of transmission for the training of young people and “sensitize farmers to the need to innovate in the evolution of the farm”. Two years ago, a number of farmers set up the Zurkaitza transmission network, with the aim of strengthening ties between young people who are willing to leave the farm and those who want to go. They work in the interior in general, as speculation on land on the coast has created impossible prices for young people.

A farm, a victory

The EHLG member explained that young people who want to learn how to grow need to be "crossed" and have to meet with those who want to train. “We have farms where transmission has been very well carried. In Senpere, for example, a farmer has two daughters, but they do not want to follow the path of their relatives and three young people enter from outside.”

He also thinks about difficult experiences, those coming from outside are not always seen with good eyes and everyone can understand his project. “The young man who starts may feel that his house is always being controlled; we have some failed attempts in this regard. The debate also generates money; you want to rent my house, but at what price?” The union also works to set criteria.

The deepening of relations is, according to Barberena, fundamental and, sooner than later, the socialization of the theme: “We have to understand that addressing the issue is essential to think about Euskal Herria for tomorrow. We’re not going to replace all retirees, but when we save a farm, it’s already a victory.”

“With the heritage everyone wants to take their share of the cake, without worrying about other consequences”

Oihana San Sebastian Etxegarai is a lezoar currently living in Oiartzun. He and his partner have sought the baserritars without heirs, with whom they have learned the trade and have come to a transmission problem that concerns them. At the moment, their attempts have failed.

Do you have access to the cottage from the family?

My grandparents, as well as my partner's, have grown up in the farmhouse, but the two farmhouses have eaten the cities. The one of my grandmother, in Irun, is surrounded by the asphalt; the dwelling is just the building.

Where have you started the attempt to jump into the farmhouse?

I've always felt the desire to go to what the grandmother counted, and also the need to see that everything she had sown was going to be lost. We started looking at the internet and the real estate companies, and we realized it was impossible, because the prices are huge. Many of the hereditary children have been put on sale in very poor condition. We went to the City Hall to ask him what the situation was, if they knew someone who might be interested in receiving us in the house, but because of the private information they couldn't tell us anything. We also think about occupying a hamlet. The truth is, we didn't know where to go.

What were you looking for?

We started looking for mortgages and homes. It occurred to us that in some quarters there could be mature people, without heirs, who might need help, willing to receive us and transmit their knowledge. Even paying for the rent, we would live and take care of them. We would take it full of enthusiasm, despite the low level of training. I work in the tourism sector, so our intention was to work on a sustainable rural tourism model. In Catalonia we have known many cases which, in addition to the tourist offer, work in agriculture and are associated with other projects such as crafts.

What has been teaching?

We have not succeeded, people are closed and they are not trusted. They're afraid of losing material, economic. It's hard to see further. It is part of our cultural heritage; we see many dwellings fall by Oiartzun and it is sad. With heritage, everyone wants to take their share of the cake, without worrying about other consequences. I also love my grandmother's house, but we also love houses that are not ours. They're part of our culture and they're losing in solitude.

And now what?

We got into a small credit and bought a small apartment that fell in Hondarribia. We get good at ourselves, and we have a little project in our head. In the end we have seen that the only way is to work and work, until we make enough money to buy a farmhouse.

“Access must be given to young people who want to come to the village”

Koro Artola is from Areso, but in Berastegi he has a farmhouse and a family, and is from Areso. He earns the work life of the farmhouse, cultivating the herd and the land, and is convinced that the family, which has two children, will not give continuity to the work of the farmhouse. Actually, he doesn't know if he wants his children to take their witness or not, unless the job doesn't "like it so much." This does not mean that you do not care about the future of the farmhouse: “With time you get tired and thinking: What will happen next? The baserritars are aging and they leave us all the grasslands around to use them, but when you leave it, what will happen? They're getting empty.

Lack of people in the villages, and at the same time, there are many young people who are drawn to Artola's willingness to approach his work. And if someone is interested in tackling the work of the dwelling, for him the real alternative is to give access to those people. “If young people like it, they will have to agree on the delivery of land for rent or whatever.” He looks forward to the dynamics of EHLG and tells us that he has also started thinking about it. “There is no other way,” he says. “When you take someone from outside you can’t know how things are going, but even if the one who comes is a stranger, a little accompanied and seen little by little, you can take steps to keep all this going.”

However, a young man endowed with spirit and strength will not be free from the distress in which the craft of labrador is found: “There’s a lot of work and a lot of people, so you have to put in a lot of machines, and for the investment to be profitable you have to take advantage of it somewhere.”

Txotx denboraldian eredu ekologikoan ekoiztutako Euskal Sagardoaren eskaintza izango da hainbat sagardotegitan, eta hura bistaratzeko, Jatorri Deiturak eta ENEEK-Ekolurrak kupeletan paratzeko euskarria aurkeztu dute.

Lurraren alde borrokan dabilen orok begi onez hartu du Frantziako Legebiltzarrak laborantza lurren babesteko lege-proposamenaren alde bozkatu izana. Peio Dufau diputatu abertzaleak aurkezturiko testua da, eta politikoa eta sentimentala juntaturik, hemizikloan Arbonako okupazioa,... [+]

203 diputatu alde eta hiru aurka agertu dira martxoaren 11 gauean egin bozketan. Higiezinen agentziak haserre agertu dira, eta bi salaketa aurkeztu ditu FAIN Frantziako Higiezinen Federazio Nazionalak Europako Batzordean. Bata, lege-proposamenari esker botere gehiago jasoko... [+]

Laborantzaren Orientazio Legea pasa den astean ofizialki onartu du Frantziako Parlamentuak. Ostegunean Senatutik pasa da azken aldikoz. Iazko laborarien mobilizazioen ondotik, aldarrikapenei erantzuteko xedea du lege horrek. Aldiz, ingurumenaren aldeko elkarteek azkarki salatzen... [+]

Zubiak eraiki Xiberoa eta Boliviaren artean. Badu jadanik 16 urte Boliviaren aldeko elkartea sortu zela Xiberoan. Azken urteetan, La Paz hiriko El Alto auzoko eskola bat, emazteen etxe baten sortzea, dendarien dinamikak edota tokiko irrati bat sustengatu dituzte.

Datorren astean Departamenduko Laborantza Ganbarako hauteskundeak ospatuko dira Ipar Euskal Herrian. Frantzia mailako FDSEA eta CR sindikatuez gain, ELB Euskal Herriko Laborarien Batasuna aurkezten da, "euskal laborarien defentsa" bermatzeko.

Euskal Herriko Laborantza Ganbera elkartearen hogei urteak ospatu zituzten asteburuan Ainhize-Monjolosen. 2005eko urtarrilaren 15 hartan sortu zuten Lapurdi, Baxenabarre eta Zuberoako laborantzaren garapena –hori bai, iraunkorra eta herrikoia izan nahi duena–... [+]

Departamenduko Laborantza Ganbarako hauteskundeen kanpaina abiatu da. Urtarrilaren 14an bozetara aurkezten diren hiru sindikatuen ordezkariekin bi oreneko eztabaida sakona antolatu zuten Euskal Hedabideek, osoki euskaraz.