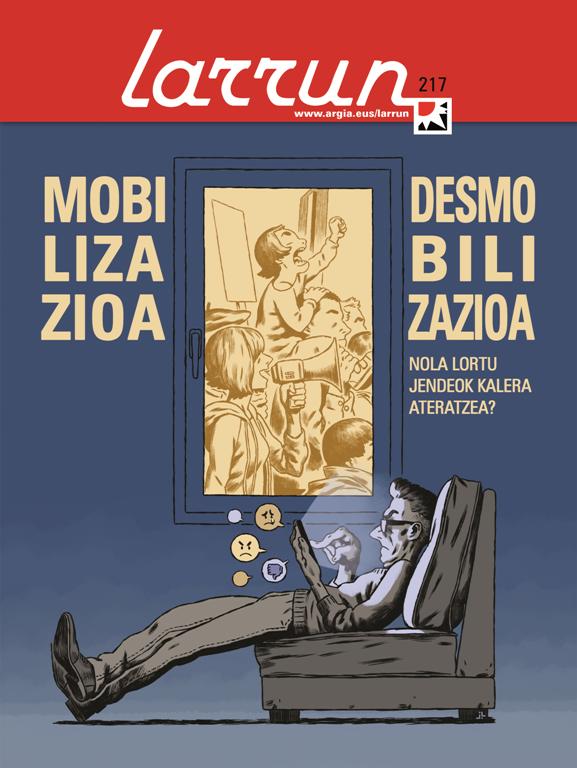

- We citizens are sometimes surprised by ourselves, despite seeing the world dance and our living conditions dance, with the patience we have. The casings are moving us, yes, but not enough to go to the street. In recent years we have visited the following members who are organizing mobilizations in search of keys: We met in Donostia with Kattalin Miner of the feminist movement. We have received Zigor Olabarria in Vitoria-Gasteiz, who has spent the last years in the Eleak/Libre movement, in the Free Territory project and in the okupado fronton Auzolana, which has as its axis the community work.And in the headquarters of Bizi! by Baiona have explained to us how the fight against climate change is conducted, these four members: Equipment: Xabier Harlouchet, Anaiz Aguirre-Olhagaray, Christian Detchart and Elise Dilet

It's not easy to feel with your legs on land when the world is dancing. This is how Zigor Olabarria sees the context: “We are in a process of changing the social model, in one of those that is repeated once for centuries. It is a change at the global level, related to climate change and the physical exhaustion of the energy model, we talk about the collapse...In addition to the global ecological crisis, in the West the welfare paradigm (which, although never developed in its entirety, sets a minimum) is exhausted, or rather, they have decided to exhaust it and that also entails major changes in the social model. What I imagine for the coming years is an apocalyptic collapse in the most extreme case, and at best, it seems to me that we are moving towards Latin American society: towards much more violent societies, with many more economic and cultural inequalities among people, where institutions only care about security... In this situation of confusion, there is a risk that society will turn to fascism. And we also have a chance to go to more just things. And those global and western variables are crossed by another in the Basque Country: the end of a cycle of struggle.”

Disorientation, weaknesses, solutions and strengths

In the described context, and with

the legs in the mud of popular construction, Olabarria feels the “general sense”, the need to speak from the weaknesses and questions: “There is a great demobilization and it is not something we are now. From Lizarra-Garazi it was said that the popular movements were in crisis, on the decline. It's not just a question of Euskal Herria. It is a contradiction, we see that if we take into account the objective conditions (as classical Marxism would say), we are in a pre-revolutionary situation and, on the contrary, what social peace there is! It’s a shame.” He explained with humor that the main conclusion of the study of history is that in the moments before the revolutions there is little evidence that history attempts to logically understand the causes of the events. He took as an example 3 March 1976 in Vitoria-Gasteiz: “If we analyze the level of conflict of previous years in both Spain and the Basque Country, Álava was an island of tranquillity. The one from Álava was a young worker, from Extremadura, with no militant experience... and in a few months the dynamics began and burned down. So, even if it seems that nothing is moving today, don’t hesitate!” Even if you feel “the general demobilization”, you have no doubt that continuing to work on popular movements is worth: “One day a high level of indigenous people may emerge, and if we have a cultivated network, a culture in citizenship, habits of self-organization, etc., the benefit that can be obtained from the moment and the force generated in it will be different from where we can channel. In addition to some concrete experiences in Euskal Herria, in recent years I have found some of the most exciting in the north in some community movements and feminisms of the evicted people of Latin America, especially in the radicals (the evolution of feminisms in Euskal Herria over these years). When we try to learn from them, it's up to us to listen, ask and doubt ourselves and our privileges to white and Western men like me. That is easily said, but I have no news from any human group that has voluntarily abandoned its privileges.”

.jpg)

Kattalin Miner, coordinator of the World Women ' s March, does not mention the direction: “Since feminism we have been saying for years that we have another social proposal.” There is no talk of weakness or demobilization, perhaps because it works in a feminism that is becoming stronger: “In the mobilizations of 8 March and 25 November, in recent years, we are growing remarkably. And that's because feminism is stronger, because there are more young girls organized, and there are a lot of people who are not organized but who are going to the demonstration." It says that it is the result of basic work, because it is working in the centers, in the media, because it has never ceased to claim on the street... He has reported that the armed struggle strengthened the hierarchization of the fights and that today the fights have become more important: “Before it was the only issue, in feminism we are very accustomed to being third or fourth in the hierarchy. In the current situation, the left-wing movement is becoming a polyphony. What I don't know is whether those movements that took precedence during the armed struggle are willing to listen to that polyphony and make it their own. That we were very willing to have this moment come? Yes. That when others have run out of that compass are lost among all those voices? Also.”

.jpg)

Xabier Harlouchet created Bizi! with the aim of preventing climate change speaks for the movement. Since its inception seven years ago, it has grown from 20 members to over 440. They have proudly told us that their actions have a great echo and social commitment and are therefore bringing about changes in reality. They are also an example of this in the French State and are building an increasingly strong international network for joint action. Also Harlouchet speaks from the fortress and tells us that Bizi! not only has the north and the road very defined: “It is a challenge to deal with the ecological and climate emergency within the framework of social justice. We have 10 to 15 years to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the radical mold and avoid the frenzy of irreversible climate. Therefore, the challenge is to see how to invigorate our militant networks and how to invite a new militant generation with a strategic vision of struggle and mobilization: to achieve broad alliances for a mass mobilization movement, bringing together reason and imagination, humor and seriousness, non-violence and determination... To change the relationships of force and achieve the decisive victories that we need and the profound change of society.”

.jpg)

Long live! movement is defined as “radical and pragmatic”. They are pragmatic, because they set objectives that are clearly defined and achievable at the time. For example, they propose concrete measures that individuals can take in their daily lives to deal with climate change, and all the Houses of the People have been given 50 technical sheets as a tool. “In the same way, these concrete measures are radical, because these goals bring with them the idea of a more global change in favor of the society we want to build.” Harlouchet says that in this way they can set in motion the dynamics of a build-up of forces, “once we have achieved the goal, we are more, we are stronger and we can set other more ambitious goals. That’s what we call leverage a strategic goal.”

Olabarria has a few certainties about where to fight, “but then, in the movements I am, I don’t know how to carry out those principles.” He explains that his goal is desertion: “Desertion of the capitalist patriarchy and its parameters. Drop out economically, politically, physically, psychologically, emotionally -- and focus on alternatives. We're going to build our resources to make this world habitable. And if there is a collapse, it will catch us with networks, with community practices…”. You have made the following specification: “Desertion yes, but for the whole of society. The communal things are very nice, Errekaleor... but that’s not for everyone.”

.jpg)

There are two essential conditions for this desertion: “On the one hand, go with people who are really worse off. Those people have to be the protagonist. And on the other hand, we have to work with those who are not politicized, because we are used to the conversations we are convinced of.” The Brazilian Landless Movement has set an example: “They go to the suburbs, to the favelas with a very strong speech and invite people to occupy the land. People join them just because they need a piece of land. Without any kind of militant experience the most marginalized enter: the prostitutes, the ones chained in the drug... But thanks to the way they are organized, they are politicized, they are empowered in the process: everyone has a great responsibility, health, school, safety...”. Back to Euskal Herria, what gives him to think about where to focus? “We are talking and talking about a culture of coexistence, but seeing the panorama we may have to worry for a few years about the most earthly needs: housing, food...” Despite its clear objective, it points to a great weakness: “We don’t have a bridge to reach those people. Who is working with poor people and really meeting the needs of everyday life, but in a depoliticized way? Church, assistentialism.” That we have to fight with those who are really weaker, that speech is spreading, but it is critical in two ways: “We don’t know how to do it in practice, and on the other hand, we don’t want it. We are still looking forward to the return of those times that we were so critical of.”

When do we move?

Let's go now to the moments when we mobilize, looking for motivational factors. Miner distinguishes three types: “It’s one thing that something happens to you or to someone around you and, therefore, you join a movement. In these cases, an injustice leads you to join the movement, identification is what leads you to join. There are other moments that are milestones. Society is getting a tough attack, let's say the abortion law, or the one we're seeing now with Trump in the United States -- if society reacts quickly, there's a huge mobilization and it's easier for people to join it without feeling involved or without feeling responsible. At that moment, people are part of something, but not organized. And, thirdly, there are campaigns that a movement organizes with a goal, in which only those who were already convinced can move, or you can do a good try and get the involvement of other people.” We

need arguments, data and reasons to mobilize, but to move, emotions move us. In Miner’s words, “emotional arguments must be given to mobilize. If we go to the issue of prisoners, we don't care much about what the law says, because we know they're not being complied with. But the injustice we feel before the law moves us. On the subject of violence we can also extract cold data to call mobilization, but a strong testimony moves us more… we are right, but we reach people through emotions”.

Elise Dilet underlines the importance of presenting a solution to mobilise people: “Bizi! It gets mobilized, because we give hope, we always give alternatives. You have to see a solution, if not, why move? In Bizi! We explain why you have to get angry, but also what to do with that anger. We give a direction, and that is hope. The engine is anger, and the steering wheel is hope. Positive emotions are also needed to mobilize.” He has also explained that humor is key: “We use humor, even if the issues are very serious. As a result, the issue is not weighed up.” Anaiz Aguirre-Olhagaray added that “the struggle is joyful.”

Olabarria

explains that the Popular Walls have defined “movement as emotional”: “They are very intense. You are next to a colleague and you know that you are going to jail two weeks a year. It is noticeable in the environment, if it is close you are fragile, touched, you live it all with great intensity...”. One of the great strengths of the Popular Walls is precisely the ability to collectivize and share emotions: “In our culture, the feeling that has been collectivized in the face of repression has been the strong side ‘I plan my face, with this I can, I encourage...’. But the sad and weak moments were for the bride, for the parents, or for those that you had to go through in silence. When all these emotions have been collectivized in the Popular Walls, when spaces have been created to share those emotions, potentiality has multiplied, both inwards and outwards. For years, we have believed that vulnerability weakens us and strengthens the enemy. And in practice, we've learned that it's the other way around, it humanizes us. It takes both, sometimes to teach the teeth, and at other times tenderness.”

Why don't we move more?

Zigor Olabarria: "We say the system leaves us out!" And it's partly true, but we know that we can be much more out, that we have a lot to lose and that that loss is the one that most worries us."

Olabarria has put his finger on everyone’s wound: “We are fully immersed in the mental parameters of power. I believe that in our lives there is no empty space that is not dominated by power. It forces us to work, to consume, to reproduce at home in a heterosexual way, to consume and to see things at home... we are receiving messages and values at 100% of the day. The system has colonized not only our ideology in sight, but also our desires, our sexuality, our most intimate aspects. It does it by seduction everything it can and by fear. Deconstructing from all this is very difficult, we are very identified.” In this sense, he explained that when it comes to mobilizing ourselves, we experience a double thought: "We say the system leaves us out!" And to some extent it's true, but we know it's not true. We know that we can be much more out, that we can be much worse, that we have a lot to lose and that we are better than in general. In Euskal Herria we are better than in the world, compared to the Spanish State... and there is a major contradiction: those of us who are in the popular movements and are concerned about the situation are not the low class of Euskal Herria. The people who work in popular movements are a upper-middle class. We don't make our daily choices on the path of building alternatives. We do so from the logic of not losing what we have and it is precisely that loss that concerns us the most. And it’s normal, we’ll also have to forgive ourselves.” To explain the effect this has on mobilization, he has brought the words of Frei Betto: “The mind thinks what they beg” and proposes to maintain honesty: “Yes, of course, the mortgage of our house and the future of our children conditions us and does not make us revolutionaries, because we are very united. Maybe we have to start from there, it would be more honest.”

From the traditional manifestation, where?

Olabarria explained that all mobilizations are rituals and that, in his opinion, the manifestation and concentration are exhausted as rituals: "I'm not saying they don't do it, but they can't be the backbone, because futures don't believe, because they don't excite us. How many years has it not been screaming in demonstrations? We are walking around, we do not hear what is said in the final communiqué... and all that is also conveyed abroad. When I'm on the street, I give it my own value. But we have to communicate differently with people and with each other. In our meetings we spent half an hour rethinking the format of concentrations, for example, making more than one banner, using videos, distributing brochures… but we were not able to provide anything extra."

Miner criticizes the tone of the current mobilisations: “I think mobilizations are a holiday today. It expresses very little anger, except in specific cases. On 8 March there is little noise, or on 25 November: while we are being murdered, we live a rather protocolous day -- I don't think that mobilisation looks as much as a battlefield. The attitude of the people has changed: we want to mobilize in peace, with joy, with humor... and yes, we have to make the revolution from humor and celebrate things, but we also have to go out into the street angry. Or dancing, but with strength. There's no cholera on the street. And outrage is good if it's channeled right." Olabarria has linked

this change of tone to the change of cycle of struggle in the Basque Country: “When we make changes, we tend to go from one end to the other. It seems that now everything has to be nice, it has to be a smile -- and of course we need to share joy, but also get angry. Because cholera is a fuel, like joy is a fuel. Being sensitive in today’s world causes outrage! If we don't get angry and don't move our guts when we see so much injustice ... It is healthy not to endure injustice. That will lead us to do something, maybe something that's not good about calculus but that's real, not a pose. Otherwise, it is not true. If we don't get the picture in the world,

it's over! In the words of Aguirre-Olhagaray, the events that most organize in Bizi! are: “And we take care of the pleasure, always have to have a nice time, eat and drink... the party.” Dilet added: “But with the background. We do not organize ordinary demonstrations.” The message could be that they would try to make themselves public more easily by organizing extraordinary demonstrations with music, with special slogans and ways of participating in a special way (for example, in the manifestation of rich disguised to symbolise the imbalance of the world’s wealth).

To reach more

Elise Dilet: "Do you have to see a solution, if not, why move? In Bizi! We explain why you have to get angry, but also what to do with that anger. Anger is the engine, and hope is the wheel."

Miner says that social movements must be ambitious, they cannot be content with their potential audience: “To reach more, I don’t think we need to lighten the discourse. People have to feel that when they move they are in favour of something radical, that is, that the message has strength. The feminist movement, on the other hand, always delegitimizes it. Therefore, if they have to delegitimize us, let it be for what we have said, not for free.” Prior to the mobilisation, he explained that it is essential to create an environment

and that the call is not limited to a poster. To do so, it is a way of obtaining adhesions, but asking for involvement beyond the signature, for example, giving each citizen the opportunity to express their adhesion through photos, videos, phrases. And he's also in favor of going to what's not the potential public of that movement and meeting face-to-face. “We have to move to places that are uncomfortable for us and where our discourse is uncomfortable for people. For example, an association of neighbors, which is not particularly feminist, and which may be almost all men. We have to surprise people when we tell them what we're doing. ‘We’d like your neighborhood association to attend this rally.’ It is clear that you have to reach people directly and that people have to feel part: “Where are the young people?” he says. Oh, it's young people who do things, eh! you should go see her. But not to take you, but to go and wait by your side, listening. The same as with migrants, they're doing a lot of things, go and see. It often seems to us that it is our real movement and that we have to assimilate others, that people are doing nothing. People are doing a lot of things, but they won’t have any interest in your movement if you don’t make this movement also stimulating for it.” In Bizi!

They also hold talks to warm up the environment before mobilizations, giving explanations and training on the subject, announcing the action and explaining its meaning.

Increasing the base, one of the keys to mobilizations

Aguirre-Olhagaray: "Bizi! proves that anyone can participate and that anyone can contribute something, even if they are not a specialist in ecology or climate change"

The presence of more people involved in the movement in daily life has made more people join in the mobilizations, both in the feminist movement and in Bizi! The members of Bizi! They've figured out how they get new people to meet easily. Citizens know the movement through the “street decoration” that many people perform every morning at the Baiona festivities: “If there are queue shifts and we paste street signs, we make a communication adornment; then we pass the messages of the year or season, according to the campaigns. Many people have known Bizi this way!”, says Christian Detchart. Those who take the step of approaching Bizi! are in an open way to participate. In the words of Aguirre Olhagaray: “Bizi! proves that anyone can participate and that anyone can contribute something, even if they are not a specialist in ecology or climate change.” According to Harlouchet, the key is plural militancy: “People with different profiles can participate… making reports and research, climbing an action or organizing spectacular demonstrations, if it is a place for all... In Bizi! You can go on militating for themes, for areas, or for technical areas: some have an interest in a particular subject and have a thematic work to participate in. Others, by area, work with their neighbors and neighbors giving in practice the issues that Bizi! works. And thirdly, participation can be technical; for example, Detchart and I are on the translation team. We can work from home and at night.” One of the

keys to participation is the “social dimension”, Aguirre-Olhagaray and Dilet stressed: What attracts “Bizi!” is also a group atmosphere. We know how to be serious and meet both of us, but we also know how to take a drink and get to know each other. We know a lot of people, we become friends -- that makes good." The feminist movement Miner has emphasized the same idea: “We have to take great care of people. If someone has mistaken a couple of times call the meeting and ask if the agenda is for problems or if they feel comfortable in the group...” Olabarria is also clear: “It’s not the same that a group that has a good environment or meets only to make decisions and share responsibilities.”

Miner says that feminism has changed a lot in recent years: “I started 12 years ago and we were very few and it was a very lonely feeling. Poor fame in the people, very grotesque arguments, a lot of powerlessness, other social movements don't need us... Now feminism has another situation, we are more protected in the group, we are not alone, social networks collaborate, also the fact that the theme appears in the media, people do not say ‘it is the stone of that of my neighborhood’. A very high percentage of women know that we are or should be in depth, another thing is that we say that we prefer to say ‘I live well, I don’t feel oppression’... each one has its own ways of survival. But from the moment you feel injustice, you name yourself and face yourself there is no turning back, you become an active agent, because the others will put you in that function: when you go to the bar, you are the one who has been in the demonstration. That's where confrontation begins, or dialogue, or whatever. It is very important that there are these marked feminists in the neighborhood. That is what we must thank those who point out: those who make us ‘feminists’ without turning back, are the ones who label us from the outside.”

In Basque, without excuses

It is a debate that always emerges within the movements, speaking in Basque or going to Spanish “to attract more people”. Miner rushed to answer: “In Basque. No doubt. And there is no translation, that is, if we put the motto on top and big of the poster, 11 attacks 12 answered, that of Spanish your violence will have answer and that of small and lower, different”. He explained how the Basque Country worked with the collective Women of the World to organize the World Women's March: “We have to go see who doesn’t know Euskera and explain to him firsthand why it’s very important that the meeting be in Euskera and we have to make these people feel part of the Basque. We ask them whether they have minority languages in their country and how they live. And how they live their language in the Basque Country. And one afternoon, we'll change three key words. And they will participate in whatever language they want and it will be translated. You have to feel that the Basque people are claiming their situation: that we are marginal and if feminism is to bring all those corners to the center, that the Basque country is also that corner. And it works. But people need to explain themselves and feel part.” He says that the Basque Country, instead of dividing it into assemblies, unites it: “Because a Vascoparlant will talk to three friends who otherwise would not exist, will make a translation, and then complicity arises.” Key? “Do it with a great deal, with patience. One of the goals of the World Women’s March was that it should work in Euskera, and since I have demonstrated that it has been so in the two-year process I do not accept excuses for anyone. It is possible, it does not slow down, it does not change the content, and we do not lose people, we gain. People lived in Euskera as if it had nothing to do with him, as if it were something other than him. And when we make them feel that, even if they don’t know Basque, they become Basque, they understand how important it is and the next time they will ask for coffee in Basque.” Harlouchet pointed out that the participation of the

Basques in Bizi! is a reflection of Iparralde's sociolinguistic figures: 25% of the members are Euskaldunes. But it has the particularity that the Basques that are not usual vasophils approach: “In Bizi! are fewer people involved in the world of culture and the rest of Basque culture.” From the outset, all external communications are made in both languages, but their meetings are held in French. At the extraordinary congress held in November, they decided to accelerate the use of Euskera, reinforcing the spaces of immersion in Euskera that the movement has within it: once a month, Bizirik! issuing, regional meetings…

Alliances: direct relations, concrete actions

Kattalin Miner: "We have to move to places that are uncomfortable for us and where our discourse for people is uncomfortable for us and us. People are doing a lot of things, but they won't have any interest in your movement if you don't make this movement also stimulating for it."

There is more than ever talk of alliances between struggles. But how is this done in mobilizations to put it into practice? Miner explains that the important thing is the direct relationships between people: "We can't make a pact with a trade union, and then we don't know who we have to talk to. Alliances are made naturally.” Following the example, he explained that if he went to the unions to seek alliances, he would go to the feminist militants of the union. He says there is no reason for some struggles to feed each other, but there is still a great tendency to appeal to his own: “We will never weaken ourselves by making alliances. When we started working with racialized women, we thought that “now our priorities will be others?” and not. Each of you will organize yours, but it comes on June 28, and there are a lot of racialized women who otherwise couldn't come, and a lot of feminists Arrozes from the World will eat there. In your daily life comes the mobilization of the other, does not ask us to be involved in the other world, but we will participate in the things that others organize. If she comes running to our feminist group asking, “Don’t you have to take a feminist kilometer?” because maybe it wouldn’t have occurred to us, and if they propose it to us, of course it would have happened! And that's where we're going to put our claim. That strengthens the Korrika and strengthens the feminist movement.” He clarifies that the alliance does not mean that mobilisation should be organized jointly: “It’s important that everyone is fighting for their priority. Let everyone be clear about their priority. And ask for concrete things from other movements.”

The great result of Bizi's alliances! was the Village of the Alternatives: “One day we took the space off the cars in the plaza and organized it in 15 areas, showing practices that are respectful of people and the environment. But it wasn't just that, but it was a road that was thought of that day. Before we have met individually with several associations, we explain what the goal is, we explain to them the topic of climate change, even if they are not there, we have asked ourselves what form the spaces give to represent our links.. making one link and another, at the end 12,000 people come together that day, with one way of doing and we have won for another”.

Repression is legitimately overcome

.jpg)

Power uses repression to neutralize the most effective mobilizations. Asked about the current picture, Olabarria replied that “socialdemocracy does not come under current legislation” (e.g. banks have to pay more than doctors or teachers by law): “We always talk about democracy in parameters, but I am 39 years old and in Euskal Herria we have never lived in the welfare states of Europe what in theory are the freedoms of a formal democracy. I do not know if they have lived in the Spanish State, but in Euskal Herria we have a permanent state of emergency, linked to the fight against terrorism, with legislation and special practices. All this was argued in the need for the State to respond to the armed struggle and that there was a society that did not respect the monopoly of political violence. Is it over and what is the picture? Some things have calmed down in the application, but in the legislation they have not repealed anything and also tightened up some things in the penal code of terrorism: the tribute, in the use of social networks... and in the ordinary legal system: in recent years new forms of dissent and protest have been created, and a large ad hoc legal battery has been developed to deactivate them. Its symbol, but not the only one, is the Mordaza Law.” One of the

biggest risks of the Moorish Law is that it applies “invisible repression”, according to Olabarria: “That is, we see repression when someone is brought to court, imprisoned... and our solidary neurons are also activated in those moments. In Mordaza Law, there's no trial, you're not going to jail, but the damage is immense. This repression is very difficult to visualise. It's harder to ask for help and you eat the fine. And their ability to demobilize is enormous.” He explained that, selectively, many militants would prefer to spend between 5 and 6 months in prison before paying a fine of 20,000 euros: “Economic repression has been used for something, when and in times of crisis. All the links we have (credits, embargoes...) are very close.” In the words of Olabarria, if it is difficult to visualize the sanctions, the Mordaza Law does an even more invisible damage: “How many rights we stop exercising because of the threat. The Municipal Police tells you that you can't record what's going on in the street, and it's a lie. But the citizen stops recording, and how do we measure the damage that this entails, the force that we lose? It’s no longer about being punished, but about us refusing to exercise our rights.” It is common for a lawyer to be consulted

before any action is taken. He says it is necessary, “but with an attorney who is a little entrepreneurial. An attorney must say, through the reading of the law and its interpretation, what margin of risk each action has, ‘at least this and maximum this’. If the lawyer is honest, he never tells us what's going to happen. And it can also make proposals, something very similar, but if you do it otherwise, you will take this risk margin away.” It is also a mistake for Olabarria to consider as clear limits the limits of what the law says: “In Herri Harresia, we committed a crime one after the other, massively and with a face. Imagine that we were facing the arrest of those accused of terrorists. And yes, they have punished people, but they have been far from what they could do, both in the anti-terrorist law and in the ordinary law. Why? Because it's a matter of strength of relationships. The key is what kind of social protection we do. And the support is very varied, for example, there are 2,000 or 200 differences in the plaza, but above all, the authorities feel that those who are not in the plaza also understand us. Depending on how we work, we get impunity.” So

what the law says is not an objective thing. Laws are applied some times and others are not. How do we overcome the repression with that gap? “Transforming the relations of force,” says Olabarria: “There may be a temptation to turn to clandestine logics of exercising rights in the face of existing repression. But the current clandestine tone weakens you and distances you from society. And I also believe that people can be more open than ever to listen, we have the possibility to reach out to people, and that's why the main line should be to continue to exercise rights visibly, showing the face and in the most massive way possible. Even with the face covered, when it is useful to hinder repression. But also then, for the purpose of advertising, without being left in the shadow: As we did with the masks in the Popular Walls, or as seen in the different activities that have been put on the net. To do so, and in addition, with color and humor, opens up the narrow margins of legitimacy that current society has. We must promote a culture of legitimate disobedience. You have to argue ideologically and do it in practice.”

.jpg)

The Bizi! They're working on civil disobedience by action. In the words of Aguirre-Olhagaray, “the actions we do are generally illegal, but what we do is legitimate. We are very calm and we know that what we do is right.” Harlouchet added 2-0 and is backed by an absolute majority of votes. When we explain the actions, people are in favour. This is the way to give the stamp of legality to legitimacy, because through accession each one has its goal, because he realizes that it is also for his own good.” He has insisted that it is precisely this strategy that manages power the worst that citizens, without violence, direct themselves towards their goal and legitimately, without respecting the law: "Because he doesn't know where to make the arrests and because he's not going to be able to play the role of victim. Violence is already depreciated and they can manage it. Not without violence.” Detchart has

brought as an example that the police went to Bizi's headquarters! in search of the kidnapped chairs in the banks. And that same repression was used to further reinforce Bizi's message!. Harlouchet explains in detail: "We took from the bank of the neighborhood nine chairs, which put faces of few friends and showed them in front of all the media: ‘these kidnapped chairs will serve better in the alterglobalist offices and to fight tax evasion, not in this bank, knowing that this bank has appeared clearly to expel a good actor’. The police came to Bizi's residence! And he drove into the car four of the chairs that were here, as if they were big pistols ... And meanwhile, the other five seats were adopted by well-known philosophers, and there began the flight and refuge of them. In the French state, the movement of the kidnapping chairs has intensified, kidnapping more than 200 seats in banks that facilitated tax evasion: For COP21, to make it clear that the money from the energy and ecological transition is in tax havens. This type of action deactivates the classic tools of state repression”. The risk was that a member of Bizi! He could be sentenced to EUR 75,000 and five years in prison for a crime of alluding to terrorism, according to French law. “But they have withdrawn in all the allegations: first they said they had stolen the chairs and then no, they didn’t want to give the DNA, and they’ve also left it innocent... Some 2,000 people met on a Monday morning to show their support and the bank has had serious image problems, as it was not a chair theft, but a tax evasion. We are confident that they will lose the pleasure of litigating the militants, seeing the ability at the moment to defend legitimacy even legally. Any demonstration is an excuse for fine. But it’s hard to give a fine knowing that both the message and the way to do so have great social recognition.”