The will of parents under the guardianship of Euskaltzaindia

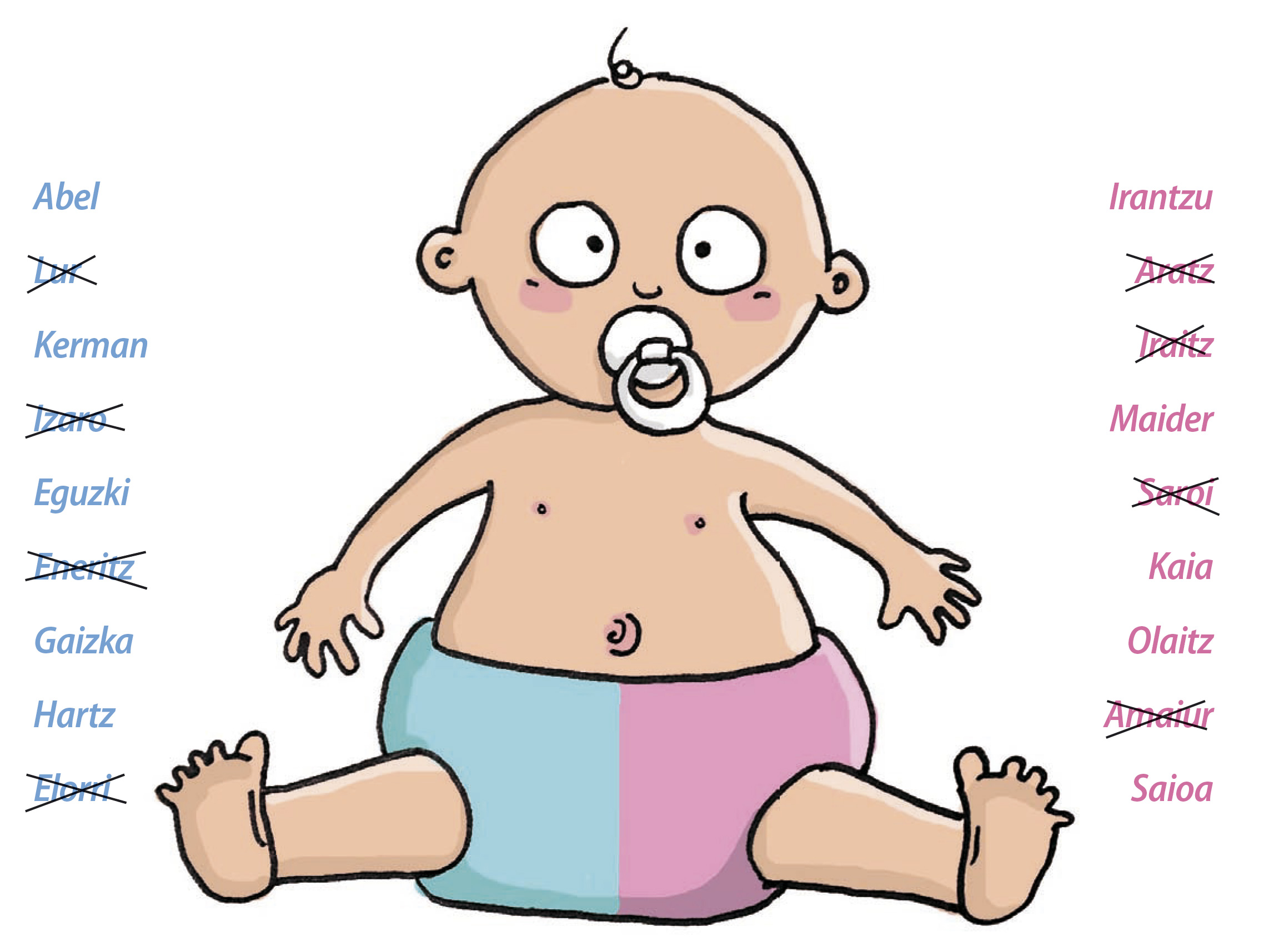

- The creation of names of people in Euskera has brought more speed than regulation. That's why we have girls and boys called Izaro, Amaiur and Eneritz. Euskaltzaindia, for its part, has consolidated the Basque nomenclature and, in her words, "advises and advises the civil registry". In the records in general, the references of this institution have their maximum expression. Now it's very difficult to put Izaro on the boy and girl Iraitz. However, the debate on gender goes beyond the incidence of certain mixed names. In the next report we try to expand the focus.

Professor at UPV/EHU Idurre Eskisabel has made a thesis entitled: Denomination and existence, Basque nomenclature and differentiation by sex. Naming a child seems to be a negligible task, but for him it is an important fact, both at the individual and social level. Names have a sociocultural identity, names are signs of identity. When they tell us about Rakeles and Ayora that we don't know, do we make the same representation of each? Do we think like similar crews Borja-Nagusia-Juan Mari-Verónica and Oihana-Aitor-Maddi-Iraitz? In Eskisabel's view, when names are selected, self-definition is being made. Those who name, today the parents, transmit why their child is Aitor or or Antoine. Individually, not so simple, but looking at the names as a whole, one can observe the social sector to which we refer.

The name revolution in

the 18th century, in Valcarlos there were five brothers from the same family, called Juan. Therefore, the importance was not the individual, but the family. Euskaltzaindia scholar José María Satrustegi was in charge of collecting the data. It does not occur to us today to give the same name to brothers or sisters. Some names, like Zipriano, Serapio, Mari Jose or Felicita, would barely use them. Now Aiora, Ane and Oihan are in fashion. There has been a major revolution in the names of people from the late 1950s to the present day. In this revolution, the names have changed, the meaning of the names has changed, and unlike before, now parents decide what the name of the newborn will be. Eskisabel believes that there has been no change in one thing: the gender difference. In general, society, and in so far as it is appropriate to regulate language, Euskaltzaindia prefers some names for boys and others for girls.

The name revolution is not only a matter for the Basque Country, but has also taken place in Europe and in the West. Another thing is that in Euskal Herria the linguistic factor has been decisive.

Until the early twentieth century, religion had great power in naming and corpus formation. At every moment and locally, the Gazetteer has been regulated by the most powerful institutions. So for centuries, religion has had a lot to say. It was then the State that took its place, although it has often been and continues to keep the church’s hand.

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, the Basque Nomenclature was established. Sabino Arana was the main driver. In Hego Euskal Herria, the time of the Republic was characterized by the rise of the names in Euskera, but there were also names that responded to the political moment, such as Freedom, Fraternity, Earth and Cosmos. The Franco dictatorship suppressed the names in Basque and those referring to the Republic. The record would erase Iñaki's name and include Ignacio. However, in the years 1950-60, along with the Basque Renaissance, citizens began to fight for names in Euskera.

To name Aratz, why do you have to be a child?In recent years, many

parents who lead the newborn to register are upset. I wanted to put the name of Earth on the boy and I couldn't. They reply that this is a name as a child, as mentioned in the lists of names of people from Euskaltzaindia. “But if I know guys and girls who are called Lur. How can I not give him the name of Earth?” That's what's happened to Axier Lopez with the newborn Earth. (Reports the incidences and their reflection on the last page of this report).

Such events have their explanation. We have already said that there has been a name revolution, new names have been created, but regulation has become slower than at the rate at which they have been produced. Thus, for years we have had ambiguous or mixed names, we have met Aratz and the girls, it has been common for family and friends of different sexes to share the same name.

Euskaltzaindia dictates standards for the normalization of Euskera and since 2001 has made a distinction in names according to sex, eliminating the ambiguities that existed until then.

Euskaltzaindia sets standards for the normalization of Euskera and since 2001 has made a distinction in names based on sex, eliminating existing ambiguities

Eskisabel in his thesis (In Jakin’s 202 you have a summary) explains in depth the criteria that Euskaltzaindia has followed to distinguish names according to sex. In summary, the author of the thesis has gathered three arguments: The obligation imposed by Spanish law, that is, that the name should clarify whether he is a man or a woman; that the Basque system has always distinguished names of men and women; that the common sense of the people be taken into account.

We have asked Euskaltzaindia herself and the Onomastic Commission has responded to us. According to the Commission, “Euskaltzaindia, like all language academies, analyzes the use of speakers to make proposals for decisions, and does not, of course, enter into political debates.” The article states that the documents researched contain names of different origins, some of them indigenous, some in Basque, and most of them external. And he clarifies: “But there is no name that serves to designate women and men, both.” He then refers to the law and says that in the South of the Basque Country, Portugal, Italy, Germany, and until 1996 in France, sex must be clearly distinguished in the names of people. In the opinion of Euskaltzaindia, “nowadays the names that generate problems due to sex are only a few: Aiuri, Maren, Amaiur, and to a lesser extent a few others. Sometimes people complain that this distribution is sexist, but we have also received petitions against it: those who believe that the name that has been given to their son or daughter should be banned from people who have other sex.” In France, the law does not say that the name has to say which of the two sexes is yours. This is what the Onomastic Commission says: “In any case, it must be made clear that most of the people who have used the Basque name in Iparralde have clearly differentiated sex and, for example, that all the Oihana are girls.”

Have names for women and men always been differentiated in Basque?

Today, the Royal Academy of the Basque Language says that there is no name that serves to name women and men, both. However, Eskisabel maintains that the discourse on sexual discrimination of the names of Euskaltzaindia has not always been the same, and gives the example of José María Satrustegi, who did a great research work on them. Satrustegi started creating the first Euskaltzaini-led nomenclature in 1972, and concluded that the old documents indicated that the names were the same for men and women. Despite this, it did not follow that path, that is, to use the same names for both sexes, using as an argument the law and the desire of the citizens. Another example that questions whether Euskera has an intrinsic sexual difference in the names. Satrustegi presented many names based on toponymy such as that of the virgin, to circumvent the legislation of Franco. So these toponyms became women's names. Later things are as follows. At the time when the same names have been used for both sexes, three nomenclatures were published, emphasizing that among the names in Basque there are some that are mixed. These appointments were made by Mikel Hoyos, Urtzi Ihitza and Xarles Bidegain.

Euskaltzaindia:

“In the documents researched there are no names to designate women and men, both”

Currently, the Euskaltzaindia

criteria have established the following differentiation criteria, with the exception of exceptions.

→ Toponyms and common words ending in -a and -e are considered feminine names; those ending in -i, -o, -u and consonants for men.

→ Add -to a name of man turns into a name of woman. Therefore, the common names ending in -i, -o, -u and consonants -a are added the feminine names (Haritz/Haritza, Amets/Ametsa..). In addition, two other ways are proposed for the training of women on the basis of men's names: that of Andre or Mari (Andregoto or Marimartin, for example).

→ There are historical names ending in -a. These are maintained.

→ In the case of toponyms, if there is a shrine of the virgin in that place, priority is given to it, and it is considered as the name of woman, abandoning the other rules.

→ The names of the Sabino Arana nomenclature are maintained despite the fact that the criterion of segregation is considered to be contrary to that of the Basque language, as they have been widely acknowledged.

The lost option

Eskisabel would say that it has been a missed opportunity, that Euskaltzaindia had a solution to lay the foundations of a new model: I could say that it dictates linguistic rules for Euskal Herria and therefore does not have to conform to Spanish legislation, especially when that of France creates a very different context. I could also say that in our tradition, mixed names have been born, which have been born.

Professor of the UPV/EHU, Idurre Eskisabel, says that it has been a missed opportunity, that Euskaltzaindia has a solution to lay the foundations of another model: she could say that it gives linguistic rules for Euskal Herria and that on this subject French law has followed.

However, Eskisabel does not believe that Euskaltzaindia is more conservative than other institutions and society itself because of the discourse it has made in recent years: “Euskaltzaindia has done all this to reproduce the gender system that exists today, because it coincides with the majority of society, because, ultimately, it enters into that hegemonic ideology of the sexual gender”.

When society says it reproduces the same system, it sets an example to understand behavior. When the woman becomes pregnant, the reflection of her father or her parents is as follows: if the child is born, Lorea and if Ander is born. I mean, we have some names on the head for the girl and others for the boy. Those who disagree with the sexual gender system, who want to question these differences, make a different reflection when the child arrives. Some have made an effort to invent new mixed names. Others have tried to use names that until recently were mixed, be it a boy or a girl or a boy. These fathers and mothers have become angry because Euskaltzaindia has opted for a distribution based on sex and the problems to name taste. In Eskisabel’s view, both examples are rare, although in recent times these types of tendencies have multiplied.

Continue reading Article "When Euskaltzaindia Made Penis A Linguistic Problem"

Izena eta izana ezbaian. Euskal izendegia eta sexuaren araberako bereizketa gida praktikoa udaberrian aurkeztu zuten Euskal Herriko Bilgune Feministak eta Emaginek. Euskarazko izendegiaren binarismoaren inguruko gogoeta piztu nahi dute.

Apirilaren 26ko aurkezpenean gidaren egileek adierazi zutenez, izenak gure izaeran eragiten duenez, gure izana eraikitzeko elementu bat gehiago da. Lorea izena duela esaten badigute iruditeria bat etortzen zaigu burura, besteak beste neska dela, eta Harkaitz dela esaten badigute berriz, bestelako iruditeria. Sexuaren araberako izenak ezartzea gainditzea proposatzen dute gidaren egileek, binarismoa azpimarratzeko modu bat gehiago baita. Hala esan zuen Libe Eizagirrek: “Mundua geldituko al da Hodei esan eta neska batek eta mutil batek bihurtzen badute aurpegia?”.

Gidan estrategiak proposatu dituzte sexuaren araberako izendegia gainditu eta jaioberriari gustuko izena jarri ahal izateko, hala nola, ospitaleetako inskripzioak baliatzea, ustez erregistroan baino errazago onartuko dituztelakoan Euskaltzaindiaren araua betetzen ez duten aukerak; froga gisa izen abstraktuak, fikziozkoak edo toponimoak erabiltzea; Espainiako Estatistika Institutu Nazionalean begiratuta froga daiteke lehendik neskarentzat eta mutilarentzat erabili direla Maren, Aratz eta Amaiur, adibidez; kontuan hartu erregistro batetik bestera aldeak daudela, alegia, erregistroko langilearen zorroztasunaren edo malgutasunaren arabera Euskaltzaindiaren araudiari men egingo dio edo ez; genero markarik gabeko izenak ere asma daitezke, gidan jaso dituzte batzuk: Ulia, Haika, Aske, Sen, Iraun…

Aurrera begira, sexuaren arabera prestatuta dagoen euskal izendegiari iskin egiteko estrategiak partekatzeko txokoa atondu nahi dute Emaginek eta Bilgune Feministak webgunean. Bitartean, gida praktikoa 3 euroren truke salgai dago bilgunefeminista.eus-en.

Euskaltzaindiak 2001etik aurrera sexuaren araberako bereizketa finkatu zuen izenetan baina IKAren Deklinabidea aplikazioa garatzen ari nintzela salbuespenak badirela konturatu nintzen. Badaude Euskaltzaindiaren gizonezkoen eta emakumezkoen ponte-izenen zerrendetan, bietan,... [+]

Euskaltzaindiak adierazi du aurki Ministerioarekin euskal izendegiarentzat “bestelako bideak asmatzeko” harremanak hasi nahi dituela.

Izenek egungo biko genero-sistema zelan erreproduzitzen duten azaltzeko, Saioa Iraola Urkiola Bilgune Feministako kideak akordura ekarri ditu Idurre Eskisabel Larrañaga kazetari eta antropologo beasaindarraren berbak. Eskisabelek esaten duenez, "egunerokotasunean,... [+]

Abuztuaren 1eko Teleberrian ARGIAren azken aldizkarian argitaratu dugun euskal izendegiari buruzko erreportajea eta analisia izan dituzte hizpide. Etxean semearen izenarekin bizi izan dugun kasuari buruzko albistean, Euskaltzaindiko kide batek aitortu du izendegia sortzeko... [+]

“Izena eta izana ezbaian” gida praktikoa aurkeztu dute Bilgune Feministak eta Emaginek. Euskarazko izendegiaren binarismoaren inguruko gogoeta piztu nahi dute.

When it was already a choir, we came up with the idea of the Queer theory, not so long ago, and it promoted debates among friends. Young friends told us that the sexes aren't just two, they're a blast. We, on the other hand, are two, from the point of view of their role in... [+]

Kontsulta jarri beharko dut martxa honetan. 2007ko urrian erreportajea idatzi nuen Hego Euskal Herrian jaioberriaren izenaren sexuarekin eta grafiarekin dauden arau zorrotzei buruz (malguagoak dira Iparraldean), eta oraindik zalantzaz beteriko iruzkinak jasotzen ditu... [+]

- "Euskal izendegia. Ponte izendegia. Diccionario de nombres de pila. Dictionaire des prenoms" liburua aurkeztu zuen ostiralean (14) Euskaltzaindiak, Eusko Jaurlaritzako Justizia Sailaren babesarekin. Bertan, 2.264 izen jaso dituzte bakoitzaren azalpen eta guzti... [+]