- Journalism and literature. Literature and journalism. Although it’s been 50 years since Truman Capot wrote ‘Cold-blooded’, it’s a debate that is repeated from time to time: Where does one begin and where does the other begin? Are there undisputed limits that separate them? We start to look at the answers that have been given to these questions.

“Journalism is information, objectivity; literature is creativity, fiction.” It is still possible to hear in the Schools of Social Sciences the statements that represent one and the other as opposite ends. But at a time when the journalistic texts that go beyond mere cold information have multiplied, and when the frontiers between literary genres also appear a little blurred, it is common to question that absolute difference.

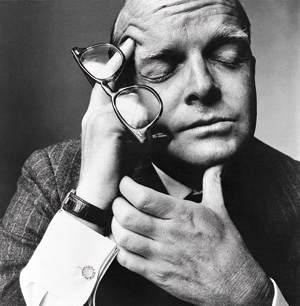

It's not a new account. In 1966, writer and journalist Truman Capote published Cold-blooded, a story based on the case of a family killed in Kansas (USA). He put the label “unfictional novel” on it, and since then it is a book that is necessarily mentioned every time the debate is approached.

It's not uncommon. Whether by the use of the same raw material – the word – or because they often see the light in the same format, the desire to define or question the boundaries between journalism and literature is regularly awakened. Yes, at least among those who act in one direction or another. In the Basque Country, the list consists of journalists and writers who in one way or another have worked as journalists: Garbiñe Ubeda, Juan Luis Zabala, Arantxa Iturbe, Lorea Agirre, Alberto Barandiaran, Laura Mintegi, Imanol Murua, Danele Sarriugarte…

Say hill to the hill

Iñigo Astiz is also a member of that long list. Besides being a cultural journalist from Berria, he has also published the book of poems Zenbat ere zabor (2012, Susa). In the interview, in addition to commenting on the border between journalism and literature, the anecdote narrated by the Basque writer and journalist Robert Laxalt will be discussed in detail. Laxalt wrote several articles for National Geographic Magazine, and he had discrepancies with the team of investigators who checked the data for all the articles he wrote for the journal. In an article Laxalt writes the following paragraph: “One day towards the end of the winter of 1539, the explorer monk Fray Marcos of Nice looked from a mountain and believed to see the fabulous city of Cibola in the distance.” The members of the research group called on the phone to protest this paragraph. “We’ve been reviewing the Nice newspapers. Even though there was snow on the ground, we are not sure that it was really winter, nor that such a view could be considered a century.” Upon hearing this, Laxalt made a proposal for disapproval: “Poned then he looked ‘one day between winter and spring of 1539’ from a ‘high hill’.” The researcher became angry: “I’ve worked for a week with four researchers, and you’re dismissing your effort with these poetic licenses.”

Astiz considers that this report shows the key to differentiation: “In journalism you cannot make the hill a mountain, and in literature it can be a hill; in journalism your commitment is to reality, and in literature to reality or the voice generated by the text.” In literary and free reports, he also believes that this is the key, to call hill to hill, even if the mountain is more beautiful. “Of course, not all realities are as likely as a hill or a mountain, and to give you an example, the difference between suspecting an interviewee that in an answer his eyes were filled with tears, to assure him that his eyes were filled with tears. In these cases there is always danger, but the important thing is to treat with respect the raw material it uses”. Moreover, when he is “lucky” to deal with a subject with a literary point, he says that he does a deeper dive than usual, as he needs more certainty to be able to access the license to be able to work more freely on the keyboard.

The director of Jakin magazine, Lorea Agirre, is of the same opinion as Astiz. At least this was stated in the article The journalist collected in the book Journalism in Euskera: present and future, published by the UPV/EHU in 2005, is not God, but was a journalist from Berria: “The writer can tell everything. And if there's a car at the scene of the murder that bothers him, he'll take him away without telling anyone. The writer is a god in his fictional kingdom. It can create, dress, shape, speak, die… anything. The journalist, no. The journalist is not a god, although many think so.”

Postfiction: when the limit is not so clear

Karmelo Landa, professor at the UPV/EHU, is one of the few professors who have participated in the debate. In his article Journalism and Literature in Collaboration, the writer collected some reflections that suggest that the border between the two is diffuse. In addition to some references that question the objectivation ability of the journalist, the concept of “postfiction” was put on the table. He explains that the texts that make up the label of “postfiction” are texts that connect the documentary work with the procedures of literature, questioning the limit of fiction and non-fiction. He said that they are characterized by the use of bold metaphors and comparisons, that although they are published in journals and obtain a fixed place in them, they maintain the specific resources of the literature.

The example of Alberto Barandiaran, current director of Hekimen, is significant. He has published several works developed in lands revolted between chronicle and fiction: We have not forgotten (Susa, 1998) Gaizkileen Faktoria (Euskaldunon Egunkaria, 2000) and Post-kronikak (Elkar, 2009), among others. In his speech on internal conflicts and knots in the drafting of the first two, he said: “These two books have emerged from journalism. They've been stories in their creation. Then they became books, because someone told me they could lengthen them, which was worth more than an article: but also because I saw that there was a story to tell.” Despite this point of departure, he argued in his speech that these books are literature and that there is no fear that the literary character of some journalistic works will be recognized. “The report gives you the freedom to write about whatever you want. To tell you what's amazing. I mean, to create. And literature is written creativity, isn't it? Why is there so much to stop giving the surname of literature to some works that are being done today? What is it, for paper? Why do they come out in the newspaper?” With this resounding assertion, Barandiaran ended his speech: “The report is undoubtedly a literary genre. That is, the emergency literature.”