- In 1940, for four months, the production and consumption of drugs were free in Mexico, according to the decision of lehendakari Lázaro Cárdenas, a physician and expert. But the United States was plunging into drug repression: Cárdenas could not cope with the blackmail of the Yankees. Today's chaos in Mexico is the son of missed opportunity.

The Chapo was liberated by the government, because it is better for Mexico than it was liberated. This has been said by Don Winslow, the author of the black novel The Cartel, who has been so successful.

Winslowk tells you the most terrible violence. He confesses to a journalist that he should not be too tired of imagination. “I’ve told you how a 17-year-old, starting at 10, took the victim’s head off and shook his face to a ball. With that face I hit the wall! I’m not able to invent it.”

How has Mexico collapsed in that chasm? Produced in Mexico for $300, sold in the United States at $18,000. That money corrupts everything -- police, soldiers, lawyers, officials, politicians, young people ...

Winslowk shows through a few figures that the only solution is the legalization of drugs. Between the United States and Mexico, about 46 billion dollars a year is spent on prosecuting drugs and repairing health damage. Because it's not legal, plus, 47,000 million tax revenue is lost. The sum spent and unpaid amounts to EUR 93 billion.

“Let us use young people to provide good education, to create companies that bring decent work, to care for those who are under drugs... Now we would save the society that is wrecking!”

Several states in the United States have begun to take timid first steps in legalizing drugs, mainly marijuana. Experts who defend this option, as well as those who win medals in the War on Drugs, are increasingly heard more frequently. But if it were to be achieved today, it would have to be said that the terrible spectacle that the leaders have supposedly made for the benefit of society has lasted 100 years.

Two books tell how the opportunity was lost in 1940: La Cosa Nostra en México del reporter Juan Alberto Cedillo y Nuestra historia narcótica del historiador Froylan Enciso. Passages for (re)legalizing drugs in Mexico.

There are signs of drug repression at least since the 18th century, when the Spanish Inquisition prohibited the peiote, which people of Mexican origin used so loosely. In the 19th century, the influence of cocaine and other narcotics and the need to legalize drugs began to be studied.

In 1917, Dr. Venustiano Carranza persuaded members of Parliament to outlaw drugs: only three votes voted against banning “substances that poison our race.” On the contrary, other doctors immediately began to demand exactly the opposite, the legalization of narcotics.

With Leopoldo Salazar at the head of Dr. Viniegra, they managed to convince lehendakari, Lázaro Cárdenas. The Federal Drug Regulations were published by the Official Gazette of Mexico on February 17, 1940.

Brief Calm Before War

According to Juan Alberto Cedillo, the Mexican state wanted to assume the monopoly of prohibited drugs, thus preventing consumers from having to resort to traffickers. During the months of the decree, the State granted marijuana cigarettes free of charge to the prisoners who asked for them, just as it had distributed the substance at affordable prices to street heroin addicts.

“Cárdenas had introduced the law to the United States, explaining to their officials that it was impossible to interrupt drug trafficking, because he had purchased special agents as a police officer, the force of some traffickers was so great,” says Cedillo.

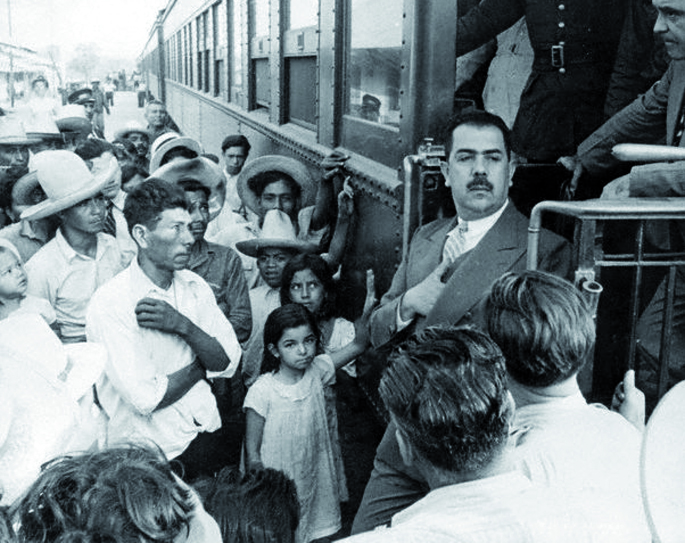

One of the main myths of the Mexican left is Lázaro Cárdenas, a man easily treated with the plain people, who took steps in the reform of agricultural lands, which opened the doors to those who fled the Spanish civil war. He justified the regulation of drugs in 1940 with arguments very similar to those still cited in the twenty-first century.

It wasn't an outburst of Cárdenas. Mexico enjoyed a great deal of influence at the time between international governments and the League of Nations, the predecessor of the UN, and other authorities also talked about eliminating bans and regulating drug use. They had realized that the alcohol ban only served to strengthen the Mafia.

The reaction of the United States soon arrived. Cárdenas met face to face with Harry Anslinger. Anslinger has been the guardian of the orthodoxy ban on narcotics in the United States, from 1930 to 1962, at the head of the Federal Narcotics Office, with Roosevelt, Truman, Eisenhower and Kennedy from President Hoover. 32 years of inexhaustible mandate.

In 1940, for four months, drug traffickers were in distress in Mexico, ravaged by drug regulation. But the United States, after a tough campaign by Anslinger against the documentation of Mexican doctors and narcotics, sent an ultimatum to Cárdenas: either the law would be repealed or Mexico would run out of drugs. At that time, as now, the United States controlled the drug industry, especially the production, so it now owns sufficient patents.

Soon Cárdenas could not overcome the pressure of the gringos. On 10 June the Regulations on Drug Addiction were suspended. In the autumn elections, in place of Cárdenas, although with the same PRI, Manuel Ávila Camacho came to the presidency. Ávila was clearly located in the trench of the veda. The world was at war and the United States was not kidding.

In a few months, Ávila sent an army in a military operation against heroin producers to Sierra Madrid, the region known as Triangulo de Oro. From there is Joaquín El Chapo Guzmán, the famous leader of the Sinaloa cartel, who had recently escaped from prison by a tunnel that a government contract would not have passed through better.

Always sinaloa. In the 1970s, when peasants in the region benefited from the expensive prices of heroin, the Mexican Army carried out violent operations due to the U.S. declared war on drug trafficking. War that has caused 100,000 deaths since 2006 and 26,000 missing worldwide.

Says Enciso, also from Sinaloa: “It has been the people who have been the laboratories of human rights inequalities and the victims have become the aggressors. The whole relationship with Mexico’s drugs is full of violence, corruption and pain, but it has not always been so, and it doesn’t have to be forever.”