Debate that is always left for tomorrow

- The left is in the throes of inventing a new model, in the midst of a paradigm shift, what to rescue from the old model, what mistakes it had made before. And as often happens in such cases, you see more clearly what you don't want. The same goes for culture. What cultural model does the left claim here? What does culture mean when it talks about citizen and participant? We have talked to BEÑAT Sarasola and Ainhoa Güemes about a number of questions.

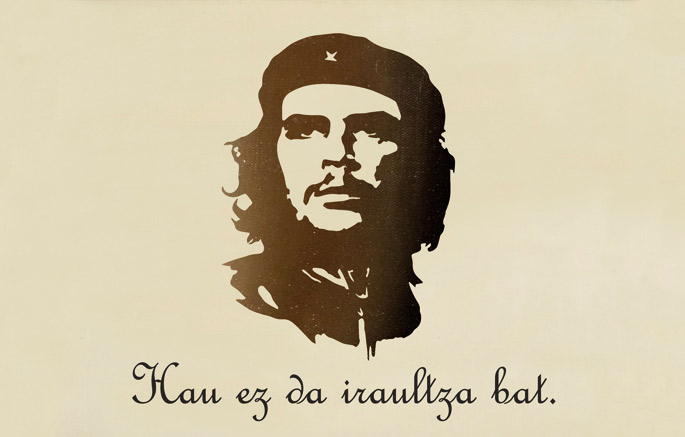

And what do you do with culture? This is the big question that has historically caused headaches to the left. Marx said that the revolution would come from the infrastructure and placed culture in the overstructure, so classical communism has considered for many years a secondary issue. Although it has subsequently been recognized a great transformative force from post-Marxism, it seems that in the movements of the left the debates on the cultural model, also in Euskal Herria, remain rather entrenched, and that in the few cases addressed, it is usually to repeat some clichés of the surface and move as soon as possible to the next theme.

Beñat Sarasola and Ainhoa Güemes have spoken about this and other issues, each from their field: from the point of view of cultural criticism – claiming, incidentally, that it is a plane that must operate with its own logic – from the national liberation movement, the second. Despite knowing that blueprints, and fundamental concepts like culture or art, don't understand them in the same way, it's clear that they're far away from each other.

Culture outside the agenda

Sarasola has considered that debates on the cultural model are outside the agenda of political parties and social movements. Bildu has set as an example what has been done in Donostia-San Sebastián: “To what was already there, only the Basque quota has been added. They have not made radical changes, they have not really risked, there has been no boldness in culture.” However, it does not seem to him to be an exclusive problem for Bildu. In general, he warns of the “lack of ideological support” around these issues. In addition, he considers that what can be done from the institutions has its limits, among other reasons, because at this moment in the Basque Country there is no cultural movement dynamizing, there are no groups of strong artists. “The things that are done are weak and very limited.”

Güemes, for his part, believes that the national liberation movement has demonstrated a tremendous level of creation. “We have constantly created those elements that make us as a people, from freedom and courage. We have managed to reconcile the whirlwind of politics with the sustainability of art. Our problem is not that we lack creative people, but that we are fighting state-wide war machines.”

For Sarasola, the left usually uses a concrete formula when it feels lost in cultural issues: to apply progressive and revolutionary models in other areas, political, social, etc. in culture. But in doing so, he believes that there is a risk of creating a conservative model, “because culture and art form an autonomous framework and have their own ways of functioning.” Güemes, for his part, for recognizing more autonomy to art than to culture, believes that the activity of creators is conditioned by cultural values and the political situation. “The importance of banners in our society, the naturalist references, the weight of this low-intensity war, the flags, the Pasadena... all this iconoclasm affects us deeply, both for good and for evil. It is no coincidence that when ETA handed over the weapons it left behind Picasso’s Gernika. Our strong imaginary is a mixture of political strategy and artistic expressions. We don’t know how to distinguish the art from politics.”

What is “citizen and participant”?

Sarasola says that the two words that have been mentioned so much lately about the cultural model can be stupid. “The citizen and participatory culture can be, for example, the one that moves the most, while the minority is not a citizen and participative. That's a perverse, culturally very conservative logic. Cultural and artistic transformation occurs almost always in minority areas”.

However, what is considered massive is not really massive. As an example, he has set an example of the Sortzen Cultural Association project, which has brought together various body builders. “Kursaal was filled with Basque groups and sold as if it were a great success. The merit of achieving this will, in any case, be in terms of production. But, artistically, this initiative is worth little. And that is that what is proposed there is dead culture. How many people who went to listen to him will create something else in some cultural expression? Nobody. Cultural value is not measured in figures, culture can influence exponentially.” Sex Pistols recalled the great concert they offered at the Lesser Free Trade Hall in Manchester in 1976 in England. There would be barely 40 people among the listeners, but not everyone: Morrissey, Ian Curtis, Pete Shelley... in part pushed the concert's fascination to create their own music bands -- The Smiths, Joy Division, The Buzzcocks. That night he's gone to books as one of the most memorable moments in rock history.

Güemes explains how he understands participatory culture: “With these words we claim that the benefits of art reach more people to innovate intellectually and initiate processes of change.” Art also recognizes an exponential value: “It has to pollute, extend that abstract wealth and make it available to people. Of course, for this it is essential that there are people who seek, who are committed to internal metamorphosis, who are involved in collective freedom, who want to create a more beautiful place.”

Art, a stimulating doubt or a tool of self-affirmation?

“When you claim that good art is usually created in minority areas, they accuse you of elitist,” says Sarasola. Cultural critic Greil Marcus has brought up a quote that has been launched provocatively: “In art elitism is revolutionary.” What did Marcus mean? “An artist has to question your ideas, supposed truths, etc. Art must shake up all the prejudices that are considered known in society. Not always directly, often indirectly. And those attempts are minority because they're not comfortable for people. People seek self-affirmation, push leads them to know what we are, what we have been, and that gets them in museums, in textbooks, in general, when art becomes heritage. But real art, when it is created, must get the status quo cracked.” Remember musical examples: “No Dok Amairu and the Basque Radical Rock, for example, do not have a revolutionary effect today, but are cultural mechanisms of self-affirmation. What do people have to know as a story? I do not deny that. But nothing new will creatively emerge from these movements.”

The status quo is described by Güemes as follows: “The capitalist machinery keeps repeating a fed reality to us, and that does not allow us to get out of this historic blockade. Capitalism is capable of reinventing itself, but not as an inexhaustible source of diversity and creation, but as a way of seriously producing its deficiencies.” In his opinion, if Euskal Herria does not want to be assimilated, he has to face a challenge: “Our artistic practice and our cultural manifestations must move away from the instruments of mass spectacle. We must escape stereotyped forms of commercial culture and advertising language.”

Deep down, Güemes and Sarasola have a basic discrepancy: what art has to get to be good. In the opinion of the first, “art is a militant element in its essence, it self-affirms us as people and as a community, and it makes our project last a long time”. The second, on the other hand, believes that art that doesn't question the status quo, affidavit art, is bad, de facto. With a more accurate idea: “Not everything that is minority is good, and everything that is massive is not bad. What I'm saying is that good art, insofar as it's uncomfortable, is usually a minority when it emerges. Then it can become something massive, but at its origin it has to be able to produce that effect.” In his opinion, patriotic art achieves precisely the opposite: instead of bothering, it creates a kind of relief for the receiver.

Sarasola believes that the Left has a historic problem with afémative art, and now, with this issue of “elitism,” it has turned around again: “How very fair and clear claims are made, there is a tendency to reward such artists. But that, artistically, is a very conservative thing. Many ideologically reactionary writers are much more revolutionary in their creativity than many on the left.” Güemes sees nothing of that around him: “It is true that our creative strength often seems exhausted, especially by repeating some messages, such as the refrains of manifestations. But I think it's just an illusion. It is the socio-historical reality that reduces our creative capacity.” However, it recognizes that in these times art archetypes are not particularly good for politics, however excellent the archetypes of a given culture are. “Mediocrity is what dominates, also in our party. Leaders are not always, but they are often mediocre.”

We have known Aitor Bedia Hans, a singer of the Añube group for a long time. At that time we were reconciled with BEÑAT González, former guitarist of the Añube group. It was at the university time, when the two young people of Debagoiena came to Bilbao to study with music in... [+]

Two years ago Urdaibai Guggenheim Stop! Since the creation of the popular platform, Urdaibai is not for sale! We hear the chorus everywhere. On 19 October we met thousands of people in Gernika to reject this project and, in my opinion, there are three main reasons for opposing... [+]

With this article, the BDS movement wants to make a public boycott of the event to be held on 24 September at the Guggenheim in Bilbao. In it, they will have the presence of the renowned Zionist artist, Noa, who will present his last record work.

When, in the context of the... [+]

Mende batean, Baionako Euskal Museoak izan duen bilakaeraz erakusketa berezia sortu dute. Argazki, tindu edo objektuak ikusgai dira. 1924an William Boissel Bordaleko militarrak bultzatu zuen museoaren sorrera, "euskal herri tradizionalaren" ondarea babesteko... [+]