This has not happened in Madrid

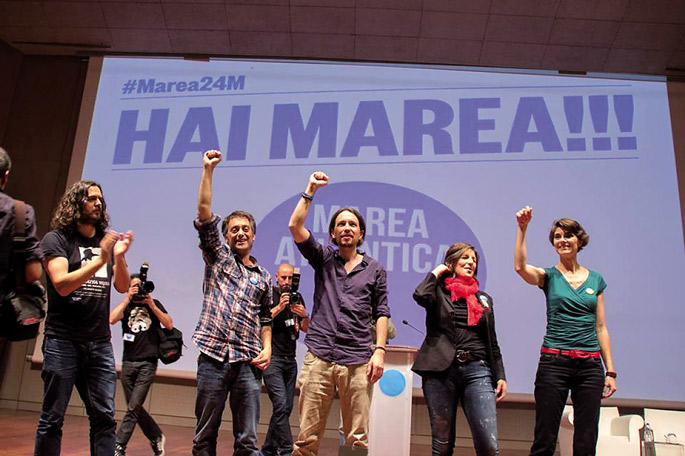

- The candidatures that have subsequently been proclaimed with the generic label “tides”, in general, were very successful in the municipal elections of May in Galicia. The coup took place mainly in the three main cities of the province of A Coruña, where the city’s mayor was obtained. The leftist parties and numerous citizens’ movements now want to use the strength of that wave to repeat the formula in today’s Basque and Galician regional elections. But unity is not that easy.

In the last days of January 2012, a significant part of the politically organized Galicians crumbled the schemes and crumbled the heart of a sector. After years of intense tensions, the national congress of the BNG held at the fairgrounds of Amio (Compostela) paved the way for a break-up in the sovereign party. The split occurred shortly after, when the Encontro Irmandiño group, led by Xosé Manuel Beiras, left. Other groups and militants were soon to go down the same road. It would be wrong to think that this fact is the origin of the municipal applications called tide that obtained unexpected results on 26M, but it would be equally wrong not to realize that one of the starting points of this political event is the Blocking division. The tides have given a great surprise to much of the Galician political ecosystem. Although some analyses have suggested this, it is difficult to explain them as a mere reproduction of the Madrid political dynamic.

Half a year after the BNG broke up, the president of the Xunta, Alberto Núñez Feijóo, decided to bring forward the elections scheduled for spring 2013. Among the factors that led the popular to bet on this advance, the main one was that the opposition was virtually annulled: The PSdeG-PSOE did not have its candidate for re-election, while the BNG did not have a complete digestion of what happened in Amio.

Meanwhile, the groups away from Block, as well as the people and organizations that approached them, were in full boiling period. Part of the provisional inscription Novo Proxecto Común had become a Nationalist Anova-Irmandade, led by Beiras, and other small groups, along with individual militants, had begun to launch the centre-left Galician party Commitment for Galicia. They all rushed to find meeting points for the elections that had been called by surprise.

Cometa AGE

Another of the tidal germs was born in this context. In several forums it was certain that Galician voters would have to choose between the union of the three parties that formed Parliament for more than a decade – the PP, the PSOE and the BNG – and those that had left Blocks, but then started to change the script.

After several years of contact with the Altermundane movement at the World Social Forum and similar spaces, and after watching carefully what happened in the M15 and its explosion, Beiras and its environment intensified calls to form a “broad front” against the right. On that front, as they explained, there was not only room for the sovereign left, but there was room for other forces, such as the Esquerda Unit (EU). Finally, the EU joined Anova and together with Espazo Ecosocialist and Equo created Galega Alternative of Esquerda (AGE).

Journalists Anxo Lugilde De Beiras a Podemos: As explained in the essay A política galega nos tempos da troika (from Beiras a Podemos: Galician politics in the troika era), the historic Abertzale leader assumed the leadership of an electoral instrument created to channel on the left the indignation accumulated during the years of crisis and severe cuts. Its charism, together with the main motto to end the mandates of the troika, in this case identified with Núñez Feijóo, was sufficient for the AGE to receive votes from both nationalism and the disappointed sectors of the PSOE, as well as from the small United Left electorate in Galicia. Thus, in just one month, the coalition chaired by Beiras managed to become the third force of Parliament, with nine seats, two more than the BNG.

The AGE election campaign was very intense, almost insane. Beiras, about to age 80, was in his second political youth, getting all the halls to be full. Behind her, many members of the newborn organization wondered “what’s going to happen” and what the size of the success would be if the campaign could last a couple of weeks longer. Among these people was an anonymous collaborator, a professor at the Complutense University of Madrid, Pablo Iglesias. A year later he launched his AGE: We can.

And then We Can

As you have pointed out on more than one occasion, Churches had very much in mind the experience in Galicia. She was an advisor to Yolanda Díaz, EU coordinator, in this Beiras campaign, and that experience was one of the keys to Podemos’s design. In the Galician laboratory, Iglesias realized that the indignation in the elections had good results, and he did so in the European vote of 2014, with the same role as the AGE had played two years earlier in Galicia.

In Galicia, the formation of Churches drew many votes from the fishery that had opened the AGE. The AGE itself began to suffer some of the hakes of the so-called “old politics”. For example, the bitter inner ridge caused the march of a Member. Like the fragmentation of the BNG, these facts are insufficient but necessary to understand the onset of the tides.

The Atlantic Tide and its explosion wave

Almost without time to breathe after the earthquake of the European elections, in mid-July, the Atlantic Tide, initially signed by 99 people, began to appear dispersed in A Coruña. “We are born to return 99% to A Coruña,” they said in their first public act. Among the more than 300 people concentrated on the site were known faces of left-wing forces and Basque forces. “This is a process of addition and not a dialogue between leaders,” they explained. His goal was to build a network across the city, a year later, as was said, to fight PP for government. At that time, the people held there the absolute majority they held.

The Atlantic Tide process continued through countless sectoral meetings and the creation of enthusiastic neighborhood tides that looked at him curiously and, in some cases, with envy from other Galician cities, especially those ruled by the PP. In the mirror of A Coruña, for example, the people who decided to push the Compostela Aberta platform in Santiago de Compostela looked at themselves. Something similar happened in Ourense and the result was Ourense in common. The same is true of other cities and chiefs of the region. These births occurred in a sea of uncertainty, one of the main ones, about the relationship of the new movements with the BNG and vice versa.

Single reading, impossible

It is very difficult, or simply impossible, to analyse the tide phenomenon as a unique phenomenon, as its realities are very different, almost as much as the results obtained in the elections. In the Atlantic Tide, for example, from the beginning, people with a long history of nationalism and sovereignty participated, as well as members of the leftist political forces of the State (EU, Podemos) along with the popular movement of A Coruña. The process was quiet, lasted months and the result was a list headed by a consensus candidate: Xulio Ferreiro, magistrate and professor of law, with experience in basic nationalist movements, but without prior experience in the front line of politics.

Although the process was much faster, so did Compostela Aberta. The platform, in any case, did not start at all until Martiño Noriega, Anova’s second, elected mayor of Teo with BNG in 2007 and 2011, agreed to be the list leader. Thus, it became the “tractor” of the political work carried out in the previous months. At the same time, in some municipalities two ‘tides’ were created. In Ferrol, for example, it was Ferrol in Common, mainly composed of people from the AGE area with some from Podemos, and Marea Ártabra, which brought together members of the party of Pablo Iglesias and other sectors. In Orense, on the other hand, what initially resembled the processes of A Coruña and Santiago de Compostela, was bankrupt, as the internal elections were very confusing and generated a violent conflict between its members.

Results

From these elements, in 26M the Galician tides were very successful in the three cities of A Coruña. The Atlantic Tide, Compostela Aberta and Ferrol in Common got the mayor, the first two with sovereign heads, while in the case of Ferrol the new mayor, Jorge Suárez, is a member of the EU. Some 70 candidatures made in the Galician territory come from different backgrounds, some of the sum of those that have left the BNG, others from the local versions of Podemos… In this context, it is difficult to explain what happened as a mere repetition of the phenomenon of

Podemos – what happened in Galicia is prior to the formation of Churches – or as a simple consequence of the rupture of the BNG. In the forthcoming Spanish elections, and especially in the Galician elections in 2016, it will be known whether a new political space is being consolidated, arising from the confusion between sovereigns and the rupturist and federalist left, or whether these alliances will remain in a mere anecdote of a few municipalities.

Galician tide?

After the good results obtained in the municipal elections, the demands to create a Galega Tide began almost immediately. It would be a candidature for the Madrid Congress, which would serve as a test for next year’s Galician elections.

There have been many political steps in favour of unity, some very innovative. For example, the BNG’s rejection of its acronyms to facilitate the establishment of the “Galician national candidacy”. Demonstrations in favour of unity have spread here and there, and contacts between the political forces on the left of the PSOE have multiplied, with one exception: BNG and Podemos haven't talked.

At the same time, two movements – I find Cidadán for a Galega Tide and Pola Unidade – composed primarily of citizens but also with party participation, have worked in favour of a unitary candidature. A good election result can lead to the presence, for the first time in history, of a Galician group in the Courts of Madrid.

The actors involved in this intense process do not dare to predict what the outcome will be. No one wants to abandon a hypothetical unity beforehand. However, more than one has announced that the Marea brand will eventually integrate Anova, Podemos, the members of the municipal candidatures and even Esquerda Unidas, while on the other hand a sovereign base candidature will be created around the BNG.

Maiatzaren 24ak garaipen zaporea izan zuen Galiziako ezkerraren eta abertzaletasunaren zati handi batentzat, baina politikan ospakizunek labur irauten dute –begiratu Greziari– eta garaipen bakoitzaren ostean beste erronka batzuk iristen dira. Mareek ere badituzte eurenak, bai udaletako lanari dagokionez, bai euren eboluzioari eta nazio mailan egituratzeari dagokionez. Erronka horiek gainditzen asmatzearen menpekoa izango da haien arrakasta, eta arrakasta diogunean ez gara hauteskundeetan emaitza onak lortzeaz ari soilik, baizik eta –batez ere– jendartea eraldatzeko benetako gaitasuna izateaz. Hiru erronka erabakigarri nabarmenduko ditut.

Lehenbizikoa, inork kontuan ez duena, herritarren parte-hartzea mantendu eta handitzea da. Hautagaitza asko, funtsean, Anova eta Esquerda Unidaren (EU) arteko koalizioak izan ziren, baina beste batzuek gizarte eragile asko elkartzea lortu zuten. Etorkizuna bermatu nahi badute, bai batzuek bai besteek euren oinarriak zabaldu behar dituzte, eta ez dute utzi behar hauteskundeetako sukarraren ostean parte-hartzea apaldu dadin.

Bigarren erronka nagusia programa guztiz definitzea da. Ulergarria izan daiteke autogobernuaren gaia, Galizian berebiziko garrantzia duena, udal hauteskundeetan eztabaidaren lehen lerroan ez egotea, baina erkidegoko eta estatuko bozetan erabakitzeko eskubidea balizko Marea Galega baten zutabeetako bat izan beharko litzateke. Oraingoz, badirudi tartean dabiltzan ia eragile guztiek argi dutela Madrilgo Kongresuan talde galiziarra izatearen beharra, Konstituzioaren erreformaren aukera gerta daitekeenean. Bestalde, arlo ekonomiko eta sozialetan hartzen diren jarrerek adieraziko dute mareak beste PSOE bat besterik ez diren, edo 78ko erregimena benetan eraitsi nahi duen mugimendu batez ari garen.

Azkenik, beharbada Marea Galegaren erronka latzena izango da alderdietako buruzagitzek prozesua beren kontrolpean hartzea eragoztea. Benetako herri frontea nahi duenak ez luke burokrazien mugimenduen zain egon behar. Gauzak ondo eginez gero –A Coruñan hala gertatu zen– alderdiek bi aukera baino ez dute izango: gainerako eragileekin berdintasunean bat egitea, edo hauteskundeetan zartakoa jasotzea. Berdin dio Podemos, EU, Anova edo BNG izena duten.

Raul Rios

(Novas da Galizako

kazetaria)

“Galiziar mareak” esamoldea erabiltzen hasi ginen, maiatzeko udal hauteskundeetan herritar plataformek lortutako arrakastaren ondoren. Hala izendatutakoek ezaugarri komun asko dituzte, baina ez dira elkarren klona, eta espiritu berean oinarritu arren tokian tokiko dinamiken isla izan ziren.

“Marea” izendapen bera ez dago hain zabalduta. Sortutako 70 udal mugimenduetako –Galiziak 314 udal ditu– gutxi batzuek baino ez dute izen hori. A Coruñako Marea Atlantikoa izan zen lehenengoa, eta ezagunena ere bada, ez hauteskundeetako arrakastagatik bakarrik, alderdi politikoek haren barruan jokatzen duten rola bigarren mailakoa izateak erreferente “herritarzale” bihurtu dutelako baizik. Askok uste dute horixe izan beharko litzatekeela Marea Galega handi bat sortzeko eredu egokiena.

Mareek hiru ezaugarri interesgarri dituzte. Lehenengoa da oraingoz hirietako gertakaria direla. Batez ere Galiziako zazpi hirietan eta beste zenbait gune urbanotan daude, galiziar gehien-gehienak bizi diren tokietan. Bigarrenik, inongo alderditan ez dabilen pertsona askok parte hartzen dute mareetan. Kasurik nabarmenena A Coruñakoa da. Eskuratu zituen hamar zinegotzietatik, zazpi ez dira alderdi bateko militanteak.

Hirugarren ezaugarria galiziar nazionalismotik datorren jende kopuru handia da. Horietako asko, noski, esparru abertzaleko alderdi handiena den BNGtik datoz, batzuk independente modura, A Coruñako alkate Xulio Ferreiro esaterako, beste batzuk militante izandakoak. Bigarren multzo horren barruan nabarmentzen da Martiño Noriega, Santiago de Compostelako alkate eta Anovako nazio bozeramailea Beirasekin batera.

Une honetan, Marea Galega baten sorrera Galiziako politikaren erdiguneetako bat da. Hainbat deialdi egin da herritarrek batasun hautagaitza baten sorreran parte har dezaten. Udaletako mareek ere ekarpena egin dezakete, hala nola PSOEren ezkerrean dauden eta Galiziaren nazio izaera onartzen duten alderdiek. Alderdi horiek izan beharko lukete prozesuaren “ordezko motorrak”, protagonismoa herritarren esku utzita. Ardatz horiek elkartuz sortuko da Marea Galega, eta hauteskundeetako garaipena lortzeko Alderdi Popularrarekin lehiatu daitekeela pentsatzea ez da zentzugabea.

Paulo Padin Alvarez (Politologoa, Galizaleak elkarteko kidea)

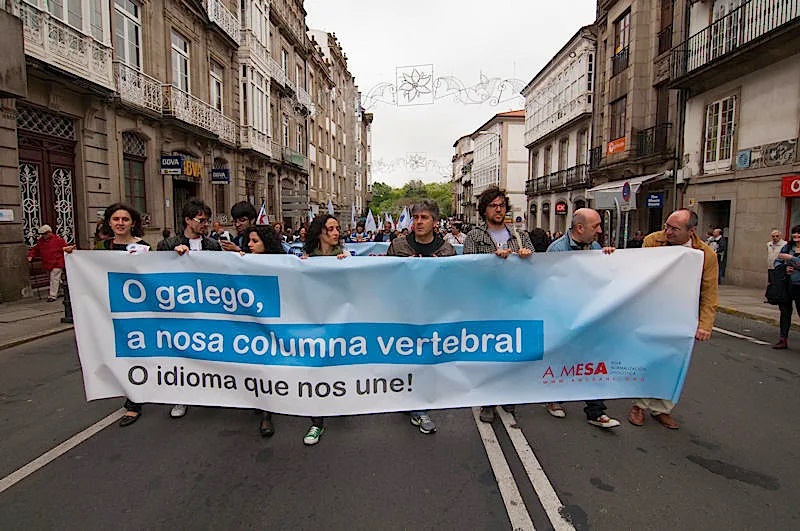

Hizkuntza bizia orain! egin dute oihu galizieraren aldeko milaka manifestarik Santiago de Compostelan (Galizian) joan den igandean. 2024ko hondarrean, azken inkestako datuek pozteko arrazoirik ez zuten eman: ezagutzak eta erabilerak, biek, egin dute atzera. Galera handiagoa da... [+]

A prestigious architect comes from London to a small Galician town. It is David Chipperfield, a building with offices in Berlin, Milan and Shanghai, and has a large team of buildings. An elegant, refined architecture, made by a Sir. The story begins in the village of Corrubedo... [+]

Matute wrote on twitter about statements by Feijóo in the Galician election campaign: “These people can’t win.” And they've won. BNG has risen a lot, everyone says. In TVE they say that nationalist parties do not have to be bad (they spoke of non-Spanish nationalism). They... [+]

"Sindikatuak enpresa zekenenak bezalaxe jokatzen du", salatu dute beharginek. 2014tik izoztuta duten hitzamen kolektiboa eguneratzea eta soldata-igoerak eskatzen dituzte.