Funeral Chronicle

- After 40 years of dictatorship, Franco expired in 1975. It was undoubtedly a symbolic year, because the form of the constitutional regime that would be fertilized in 1978 marked the pulse of the apparatus of Franco (police, oligarchy, justice...) and society from then on. More and more people think that the political system that emerged in that period called “Transition” has huge borders, that a state cannot be built from fear, amnesia and imposition. After 40 years, what better than looking back.

Carrero Blanco's murder changed everything. In fact, the change came from before, but when on December 20, 1973, on Claudio Coello Street in Madrid, the admiral's car flew out, everyone observed that it was a Franco without Franco. The magnicide was claimed by the Txikia command of the V Assembly of ETA, but no one believed it, neither the police nor the opposition leaders. Until at a press conference ETA members unveiled all the details of this action. “When he reached the height of our car I told Txabi: ‘Orain’. I didn’t see the car, but I saw the land going up.” Jesus Zugarramurdi, supposedly behind the pseudonym Jon, told Eva Forest in his book Operation Ogre. The conspiracy theory has extended its black hand to this day, but a couple of things are certain: there were many anti-francoists who rejoiced at that murder and those who strategically criticized it were not few. However, the one who cried was the bourgeoisie that was in the strongest apparatus of the dictatorship and that was orphaned.

Those who regard the transition as a model, those who praise the action of Suárez and Juan Carlos de Borbón at the time, are often forgotten – or it is not worth remembering – that Carrero’s death was one of the most important factors that allowed the change, and that it was the result of an attack.

However, the idea that regime change was not a matter of concrete facts or a few protagonists among the historians and the opinion leaders who have investigated that time is becoming increasingly widespread, not because of the “goodwill” of the reformist assumptions, nor because of Franco’s death. With the dictatorship the workers’ movement and social mobilizations ended: “Contrary to what most traditional stories,” says Catalan historian Xavier Domènech, “the Transition remained that way thanks to the mobilizations: they hindered the project of continuity of the regime and conditioned the agenda of political change. The change started when the King or the young man named Suárez, with the blue shirt, still didn’t think the Sicario was going to come to democracy.”

During the Franco regime many strikes were carried out, usually due to labor conflicts – in 1966 the one carried out by Lamination de Banda de Etxeberri has been stuck in the imagination of many – and since the 1970s the Burgos process aggravated the political crisis. But surely the turning point was brought by the mobilizations of December 11 1974.Ese day a great general strike took place in Hego Euskal Herria, being Navarre the epicenter: 223,000 people stopped the machines. The troubled political environment was compounded by the discrepancies in many of the factories with the bosses, following the temporary abolition of the shameful wage border imposed by the Government.

The oil crisis of 1973 led to an increase in prices and workers saw their low wages sink even further. In that "hot fall" of 1974, demonstrations began in Navarre in favor of the agreement, the result of the labor conflicts of previous months in Laminaciones de Lesaca, Poprecios de Navarra, Authi and other places. A strike was organised on 11 December last, involving the ORT, MCE and LCR-ETA (VI) organisations, which were already chairing the staff committees. As the day approached, the arrests and protests spread to numerous factories and, of course, police repression.

The Navarros businessmen did not remain silent. On 9 December it was threatened from the Diario de Navarra speaker: the demands of the workers were political, and if those who were unemployed did not go to work the next day, their offer would be withdrawn. Of course, they did not ask for trade unions to be banned because they were already illegal, but 40 years ago the Basque employers had the same argument as in a report: workers can only protest about labour issues. That says a lot about what they call Transition.

After the murder of Carrero, Arias Navarro took power and promised a new state of mind. He rushed to eat his word and spread wood like his predecessor. When they gave the "garrotte" to Puig i Antich, it was seen that the venom of the persecution of 36 by the Franco had still sunk into the bowels. At that time there were more political prisoners than ever dispersed in Spanish prisons – some 245 in December 1974. The prisoners began a hunger strike in November and there was a growing number of demonstrations in solidarity with them on the street: general strikes took place on 2 and 3 December, particularly in Gipuzkoa.

In this atmosphere of outrage, the general strike of 11 December took place. In Álava, Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa 200,000 people participated and in Navarre about 23,000. In the region of Pamplona/Iruña 70 companies stopped production completely and the university also had a great impact. The success was acknowledged by the Police itself, which counted only over 76,000 strikers in Gipuzkoa. Mass redundancies and fines will be the employer’s response to the closure of the market. So far this year, 16 companies are still not returning to their jobs.

That general strike of December 11, 1974 was the most successful of how many have been carried out in the Basque Country. Despite its work origin, the overall political context had much to do with this display of strength. Qualitatively there were also novelties: on the one hand, it was possible to measure for the first time the great impulse of the minority sectors that were on the left of the Spanish Communist Party; on the other, in the four provinces of Hego Euskal Herria the same socio-political concern was increasingly evident; and, finally, the reaction of a concrete fact that was not the general strike, society had already gone through the attack.

In fact, it was clear that with the murder of Carrero Blanco the cabin was going to fall before it arrived late, and since then the anti-francoists pushed and pulled to destroy it.

Lockdown in Posistemas de Navarra

The echo of the protests of the last general strike was still heard aloud on 7 January 1975. On that day, the heads of the company of Potarifa in Navarre condemned to another 2 months hundreds of workers, without pay or employment. The company management showed the workers the most intransigent attitude of the employer. No wonder, because the government itself was behind it. Potas was the largest company in Navarre, with almost 2,000 workers and state-owned through the National Institute of Industry.

As soon as they received the sanction, many workers went directly to the mines of Undiano and without thinking twice they entered the enclosure, starting one of the most famous enclosures of Euskal Herria.

The Maoist training ORT (Revolutionary Workers’ Organization) published a kind of calendar in which a member of the workers’ commission commented on the experience during the 15 days of the lockdown: “We have put in the chariots all the food we can and the lamps we have at our disposal; and by the time the Civil Guard has returned 47 volunteer miners we have begun the journey downhill. This is how our lockdown has started, forcefully. We have the feeling that it will be very important, we are not willing to give in as easily as the employers would like.”

The pressure exerted by the workers in the mining chambers was enormous, cuts of light, shouts from the civil guards, hunger, cold, fever... and above all, the lack of news of what was happening outside: “It presses us to think that maybe they have returned to the routine outside, there are so many factories on strike! And ours is just another...” Outside, however, a real revolution was taking place. On the 15th there was a general strike that paralysed the whole of Navarre in solidarity with the closed workers. Protests took place in Pamplona and many neighbours tried to reach the area where the mine well was located. In the papers guarded by ELA's historical militant, Ramón Agesta, there is a communiqué from the union in which the facts are gathered: “Yesterday, 14 January, 8,000 workers met in Zizur and from there we headed for the mining area of Undiano. (...) They attacked us, threw machine guns, crushed crying bombs and fired rubber bullets.”

The miners left the well on the 21st day by their own will, without causing injuries. They were dismissed and tried. But in that trial, lawyers defending the fracture, it was the company Potas that was sued, and in part the state itself. José Luis Díaz Monreal, who started working as a young person at Porates, has also investigated what has happened in recent years. In an interview for the UEU he tells what he has lived: “Since 1974 there has been a tremendous labor dispute in Navarre, but the ultimate goal was to bring down the regime and achieve democratic freedoms. During the mining lockdown there were at least 15,000 daily workers on the street, we appeared in newspapers all over the world and in the councils of ministers there was talk of the whole time of the Navarro case. It was a milestone of solidarity. (...) I remember that in a 1968 strike some CCOO pamphlets appeared for the first time calling for ‘solidarity’; we did a couple of hours at Potas. From that moment on, solidarity extended to infinity: To the dead in the 1970 Granada construction strike, to those of Ferrol in 1972 and also to the events of Vitoria in 1976.” One data summarizes the above by Díaz: In 1971 there were only 5 strikes of solidarity in Navarre, while in 1975 they were 125.

Staff Commissions

On the night of February 1975, the Abertzales Workers Boards (LAB) held their first meeting under the shutter of a pastry shop in Biarritz. The union was more than the Basque translation of the COA (Abertzales Workers Commissions), created by LAIA. The assembly movement was born with the objective of uniting all the personnel with a little Basque identity and “responding from the class perspective to the national problem of the Basque Country”, as can be seen from the first handwritten statement.

One of the founders of LAB was the historic militant of the Abertzale left Jon Idigoras. This is how the son of Juanita Gerrikabeitia is remembered in his memoirs: “In the North we gave a lot of know-how and got a lot of money. In part we went to the ‘interior’ and with the rest we bought 20 multicopists, of those who were alcohol (...). It was the first time we bought something, but the material was falling short because the union was growing. There was no alternative, for once we became ‘honest’.”

The workers' committees (CCOO) were still a sort of coordinator in the 1970s and showed enormous dynamism, that is where the creation of LAB must be placed. In 1974 there was a division in the commissions between the ECP-controlled sector and the more left-wing groups. On the other hand, there was the Basque AOC – which would then be LAK – and the traditional unions – especially ELA and UGT.

In this alphabet soup, one of the great debates focused on whether or not he participated in the Francoist vertical union. This was the case in the June 1975 trade union elections: “Let’s close the way to the employers’ candidates!” the supporters said on the typed sheets, while the opponents “Let’s not give up!” In any event, after these elections, the CCOO lost its openness and began to adopt its current form. We can say that the current trade union and fighting model took root 40 years ago, when it began to emerge from the underground.

No, no, not nuclear power stations!

In many parts of Euskal Herria, slogans were shouted for democratic rights. At Deba, however, there were other concerns at the beginning of 1975. From house to house, a black book opened the march of the lightning, and he was subjected to a sling figure with a refrain that until then had heard very little: No, not nuclear power stations. The logo designed by the sculptor Eduardo Chillida has been widely used later.

Iberduero had already put its eye on nuclear power since the 1960s. In this way, he showed his intention to install 32,000 megawatts throughout Spain and to build four plants in the Basque Country: the works were already being advanced in Lemoiz, Tudela, Ispaster-Ea and Deba.

As was the case with the Lemoiz power plant, the electricity company bought in Deba the land and farmhouses in the area, near Mendata, Sakoneta and Aitzuri, to subsequently unlawfully start the works and get the permits more easily. “Basque nuclear coast: in the hands of Iberduero” was one of the projects most criticized by the owner of the weekly Cambio 16.

.jpg) In Deba's case, the opposition of the citizens and the local institutions was greater from the beginning, and surely that's why it didn't thrive. In 1974, the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa requested a report from the US consultant Daves & Moore, which consequently denied the license to build a plant in Deba. According to the report, the population in the perimeter of 50 kilometres around the plant would be excessive and irreversible damage to the environment would occur. The Society of Sciences Aranzadi also fully opposed the project, explaining to Zeruko Argia: “Because these plants will only be seen on the side of the sea, they will not drive away tourism. Bravo, boy! Since when is it necessary to see so as not to be harmful?”

In Deba's case, the opposition of the citizens and the local institutions was greater from the beginning, and surely that's why it didn't thrive. In 1974, the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa requested a report from the US consultant Daves & Moore, which consequently denied the license to build a plant in Deba. According to the report, the population in the perimeter of 50 kilometres around the plant would be excessive and irreversible damage to the environment would occur. The Society of Sciences Aranzadi also fully opposed the project, explaining to Zeruko Argia: “Because these plants will only be seen on the side of the sea, they will not drive away tourism. Bravo, boy! Since when is it necessary to see so as not to be harmful?”

Nuclear lovers argued that energy autonomy was necessary to cope with the ups and downs in oil prices and that the Basque coast was a suitable place to achieve it economically and efficiently. At the meeting of shareholders of Iberduero in 1975, its president, Pedro Careaga Basabe, spoke to 8,000 ears of the “courage” that many technocrats would have today: “It’s a clear alternative: nuclear power plants or recession and crisis.”

On the contrary, more and more worrying news was coming from the international community about the safety of nuclear power stations. In January of the same year, there were a total of 23 reactors for radioactive discharges in the United States. The Three Mille Island accident had not yet happened, but there was already a panic about a catastrophe among the population. According to the 1978 CIS survey, 64 per cent of Basques wanted another alternative for not having to use nuclear energy.

In any case, all projects except Lemoiz were paralyzed between 1975 and 1976. Thus, the Pro-Costa No Nuclear Basque Commission was launched and the first major mobilizations began. The first anti-nuclear movement was born at Deba, but in the following years the question of Lemoiz was put at the center of Basque politics and armed conflict.

Aberri Eguna in Gernika

Among the demands of the Aberri Eguna of the 1960s, that of 1968 in Donostia-San Sebastián reached its peak. But the repression was brutal and from that year on the PNV decided “not to play the regime.” In 1975 things changed radically, the regime was out of play and the Jeltzales once again promoted a unified appeal to “express the desire to free Euzkadi from a peace outbreak.”

Most groups joined the call and, above all, two great demands were made: unity of parties and freedom for prisoners. The amnesty petition erupted in 1977, but began to germinate in that 1975 Aberri Eguna: The PNV considered the call of Gernika as an opportunity to “offer a friendship of widowhood to all compatriots who are in prison or in exile for the freedom of Euzkadi”. The Communist Party of the Basque Country was more specific: “Amnesty! That hasty squawk is breaking the walls of the prisons...”. They did not imagine that a few months later the jails would be overflowing by the state of emergency.

In  March 1975, the journal of the association Baionako hitz published a special issue on the occasion of the celebration of the Aberri Eguna. It includes interviews with politicians and personalities from the world of culture (Lehendakari Leizaola, Telesphorus Monzón, Mark Légasse..). So I saw the environment Jose Luis Alvarez Enparantza, Txillardegi: “They say that all the Basque forces are going to do something together. Or, at least, it seems that the PNV and ETA are going to do something together. But I am afraid that those in Madrid, when they see that all the Basque forces have made a call, will take tough measures to prevent people from meeting Gernika or elsewhere. The police will do everything possible to ensure that this does not happen, especially at such a serious political moment as the present one.”

March 1975, the journal of the association Baionako hitz published a special issue on the occasion of the celebration of the Aberri Eguna. It includes interviews with politicians and personalities from the world of culture (Lehendakari Leizaola, Telesphorus Monzón, Mark Légasse..). So I saw the environment Jose Luis Alvarez Enparantza, Txillardegi: “They say that all the Basque forces are going to do something together. Or, at least, it seems that the PNV and ETA are going to do something together. But I am afraid that those in Madrid, when they see that all the Basque forces have made a call, will take tough measures to prevent people from meeting Gernika or elsewhere. The police will do everything possible to ensure that this does not happen, especially at such a serious political moment as the present one.”

The Old One guessed it. On March 30, Gernika woke up under siege and the police prevented any demonstration. Among them were several Flemish Members who exhibited an ikurrina and the correspondent of The Guardian.

For or against the people

In 1974 there was an umpteenth separation within ETA, giving rise to the two groups that will later be known as miles and poly-miles. Thus, the military ETA chose to “move away from the mass apparatus”. But paradoxically, in these months ETA was the politico-military force that carried out the most attacks on the police forces.

Also, ETA(m), after a temporary pause, began a tough campaign in mid-1975, especially against the delators: “For or against the people: you cannot be in the center today. To all those who work against the people, what has happened to Antonio Etxeberria can happen equally whenever he wants.” This is apparent from the ETA Motri command statement following the death of the mayor of Oiartzun. However, the monopoly of violence was held by the civil guards.

Gernika, 15 May 1975. At dawn, the civilian guards have surrounded the dwelling in which Iñaki Garai and Blanca Salegi live, local neighbours. You know that two ETA members are hidden in the same building. After a long shooting, the pickets will mercilessly machine-gun her husband and wife to ask for help in the window, while the etarras jumped out another window and managed to flee, leaving one of the agents on the ground. One of them, Josu Markiegi Motriko, will be captured in the haystack of a hamlet, where his hands were unarmed and with the shots received. Her naked body was exhibited for a long time at the door of the benign Gernika barracks. Experience. As Miguel Sánchez-Ostiz said, civil war is not a matter of the past.

On the back of the hand sheet that was published in memory of Markiegi's death you can read a well-known poem: “I will defend my father’s house...”

Death of Gabriel Aresti

Gabriel Aresti left us a few weeks later, for a liver disease. The Belarusian poet brought a new dimension to the Basque literature, more urban and more social, and it was Harri eta Herri that showed it. He was passionate about the debate, and the same week that Aresti died another poet, Xabier Lete, wrote Zeruko Argian: “He used to tell me and write that his vasquity had two limits: truth and justice. And I told him not to demand an utopian Basque Country.”

In his youth, Gabriel Aresti learned Euskera on his own when the slope descended. Then he was one of the creators of the unified Basque. “I see a people in agony, in their last terrible agony,” he wrote once. But in 1975 Euskaldunization-literacy had already taken many steps and many more in that year (see table on the next page). Again they began broadcasting in Euskera on the radio for half an hour in the Telenorte program of RTVE; in the ikastola of Zumaia they organized a bertso-eskola at the initiative of Joanito Dorronsoro; they started the exams to obtain the title of Basque professor...

The Wolf

Miguel Lejarza El Lobo infiltrated in early 1975 in ETA(pm). Confidences to the Spanish secret services led to the arrest of dozens of people, some of whom were killed by the police at the time of arrest. Months later, the polymilis announced the betrayal in Hautsi magazine and condemned Lejarza to the “death penalty”: “We thought that with the degree of marginalization of the repressive forces in the Basque Country such maneuver was not possible,” says the page that shows a great photo of it.

That summer, the current of ETA intended to carry out significant actions. Among other things, it organized the escape of 56 ethnic groups in Segovia prison, among others. But on 30 July, thanks to the information provided by El Lobo, the police carried out operations in Madrid and Barcelona against the groups that were to cooperate in the flight. In Barcelona, Iñaki Pérez Beotegi Wilson, one of the main leaders of ETA in the Catalan capital, was arrested. John Paredes Manot Txiki accompanied him. A month and a half later, the name and life of this Basque Extremadura extended to the four winds.

Rekalde Black Book

On July 7, 1975, the Franco mayor of Bilbao, Pilar Careaga, resigned to pressure from neighborhood and family associations. The lack of urbanisation and services in Bilbao had serious problems, and of course the least affected were the most affected.

That year, the Rekalde District Families Association published Recalde's Black Book: “The entrances to schools are full of dangers, the neighborhood is embarrassed every time it rains. It has no church, no outpatient clinic, no retired house, no sports grounds, no vocational school, no nursery...”.

After several attempts, they met with Careaga on 4 March 1975. So that's when for the first time a neighbor from Errekaldebiri tells the powerful mayor in his face: Tell me! In the coming weeks, 50,000 Bilbaïs will sign a letter with the same request, as Europe Press reported. Response from Careaga: “My resignation is above the people’s opinion, it would be good if the mayor submitted us to these things!” In the end, however, he had to resign.

Last state of emergency

“The need to protect citizen peace from disturbing attempts of a subversive and terrorist nature ...”. Thus begins the state of emergency set by the Decree of 26 April 1975 in Gipuzkoa and Bizkaia for three months, the sixth and final of the Francoist period. “The state of emergency brings us back to the war environment of 1940,” said the chronicle of the anti-Francoist magazine Cuadernos del Ruedo Ibérica. In fact, fundamental rights were cancelled and the new lands were “reserved”.

4,000 people were arrested while the state

of emergency was maintained. (ARGIA file)

They tried to break this incommunication with News from the Basque Country. The arrests, killings and police assaults that were taking place – the newly created ultra-right group ATE and countryman police attacked dozens in the South and the North – the newsletter that was issued daily and thousands of copies were opened clandestinely. The manipulation of official information agencies and what really happened could be read in parallel. Thus, the case of the young student Luis Arriola, killed by civil guards on 23 May in Ondarroa is one of the most significant. According to the agency Europa Press, it was an accident, as the agent had fled the shot when the student threw himself on it. On the contrary, the newsletter provided very specific information on what happened: “On May 23, several UBI students from Ondarroa were at party with their teachers (...) As they passed past the barracks, the civil guards dragged Luis Arriola into the interior, while the latter shouted “I have done nothing!” (...) Only the Civil Guard knows what happened that Sunday morning inside the barracks. Around eight, when the court officials showed up at their parents' house, they told their mother: ‘Your son is dead. The body is already in the cemetery’s warehouse.’

According to various sources at the time, some 4,000 people were arrested during the duration of the state of emergency, especially in the first month of operation. In the bullring in Bilbao, hundreds of people were detained in the early days of May.

The tortures were also the bread of every day, as suffered by the historic militant of the left Abertzale Tasio Erkizia, who was then a priest. Many of the people now being prosecuted by the Argentine judge María Servini knew all the secrets of those dark commanders well. This is the testimony of a young woman from Markina who passed through the hands of Captain Manuel Hidalgo: “After suffering all kinds of torture, they began to touch me morally, as if I were a lost woman, saying mischief with my intimate life and doing what they wanted, they touched my whole body.” These and many other facts have never been judged, but it is late.

The situation was untenable and most of the shadow political groups and parties, except the PNV and the PCE, called for a general strike on 11 June. In the memory of many there was the success of the strike on 11 December, but above all that day the trial against ETA members Jose Antonio Garmendia and Angel Otaegi was denounced: "Let's save them! ", pasquins were constantly repeated and carteles.En Gipuzkoa involved 60,000 workers, according to the staff commission coordinator. It was the precedent of the major political strikes at the end of the summer.

War Councils

Garmendia and Otaegi were charged with the murder of the civil guard Gregorio Posadas, arrested in Toulouse. At the time of Garmendia's arrest, a bullet in his head caused a serious injury to his head. He was incommunicado for three months in this situation. In a letter sent to the judge by his lawyer, Juan Mari Bandrés, said that his was "the most rigorous and prolonged incommunicado in the history of justice in the last ten years." A nun had to teach him to speak again with a book by Escrivá de Balaguer. Bandrés asked for a study by several experts to prove that Garmendia had the isolated senses: “In these cases, it is enough six days to completely change the human personality and achieve the closest collaboration, to the point of blaming actions that are completely unknown to him.” However, the prosecutor used alleged statements made during that period of incommunicado to seek the death penalty for him and for Otegi.

The War Council was held the day after the adoption of the Anti-Terrorism Act on 28 August. It barely lasted five hours, since the 1970s, it seems that the Francoist apparatus learned a lot. However, the mobilizations were tremendous and a strike took place for several days. In this case the PNV also supported the strike – the Governing Council of Gipuzkoa recalled in Erne magazine the past macabre of Posadas to justify the innocence of the courts. An unsigned report that is preserved in the archive of the Benedictine of Lazkao refers to the mobilizations of those days, seeing how the experience of Errenteria is reported: “On the 29th the people and the working class are worse. The step is total. There's tension on the street. The struggle has hardened. The grays enter the village and carry it wild.”

CAC

Although it later became one of the major organizations on the Abertzale left, KAS Koordinadora Abertzale Sozialista was created as a platform to organize protests against military trials. Natxo Arrangi of the EIA explained in his book Memoirs of the KAS how the emergence was:

“We are in the summer of 1975 and at the moment we have: ETA(pm), Y(m), LAIA, HAS, EAS, LAB, LAS and ELI. Shortly thereafter there will be a war council against Txiki and Otaegi (...). A gigantic response to this operation carried out by the ultras of the Arias Government must be mounted. It will start to move ETA(pm), and suddenly, we do not know very well who, I think ELI, it seems to him that it would not be wrong to create a joint action that would bring together all the Basque and Socialist forces. At the end of the summer of 1975 the KAS met for the first time and mobilisations were organised.”

to the preferences of the families (Archives of the Benedictine of Lazkao)

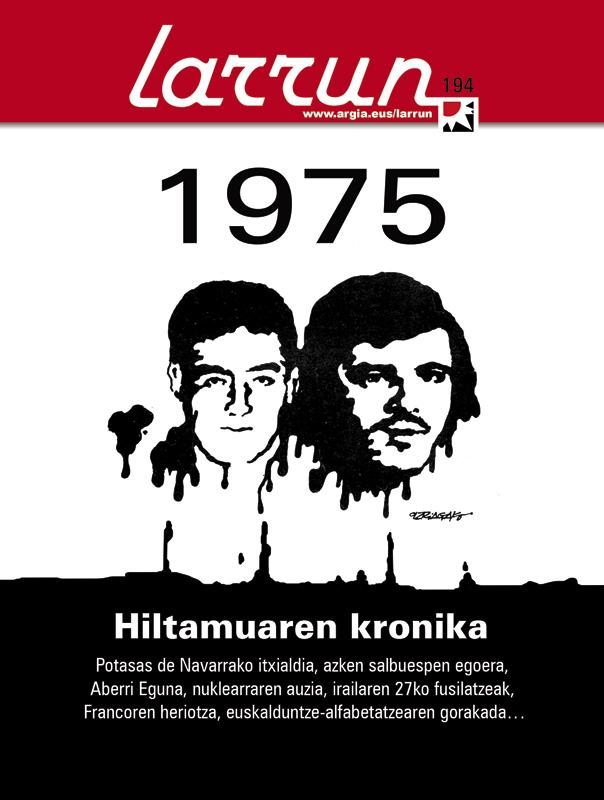

27 September

The trial against Manot, by Juan Paredes, was very quick, it only lasted a month and a half. His relatives say he was well aware that they were “going to search for him.” Born in Badajoz in 1954, he came to Euskal Herria as a child with his parents and began working very young to help the family. Txiki symbolized the same path as thousands of people, as well as leaving sweat and health, that of immigrants rooted in the culture of these territories. Many Basques of the new generations have there the origin of our being.

He was sentenced to death more for symbolizing than for convincing the government. By the characteristics of the case, by the tempos and by the political context. In fact, before Txiki there were other issues that were being raised as “sumarisimo,” but on this he was alone, so they brought him forward. In the documentary Haizea eta sustraiak, produced by Iñaki Agirre to recall the shooting of 1975, lawyer Manuel Castells explained this paradox: “The rebellion was being taken over and strong repression was needed, but it could not be disproportionate, because the international context was also there. That’s why this cause was brought forward and the rest was delayed, so that the death penalty was the only one, as there were many more people charged on other occasions.”

Magda Oranich and Marc Palmés were only four hours in preparation for the defence and on 19 September a war council was held in Barcelona against the Zarauztarra, with the aim of preparing the defence. On the 26th, the Government pardoned six of the 11 convicted on the War Councils, including José Antonio Garmendia, and ordered the killing of the others: Humberto Baena, José Luis Sánchez and Ramón García, of the armed group FRAP and Txiki of ETA.

Magda Oranich and Marc Palmés were only four hours in preparation for the defence and on 19 September a war council was held in Barcelona against the Zarauztarra, with the aim of preparing the defence. On the 26th, the Government pardoned six of the 11 convicted on the War Councils, including José Antonio Garmendia, and ordered the killing of the others: Humberto Baena, José Luis Sánchez and Ramón García, of the armed group FRAP and Txiki of ETA.

When they were shot on September 27 and later, there were protests throughout the Basque Country and abroad. In many European cities there were incidents, boycotts and high-level political accusations. Franchising was weaker than ever. “Isolated in the bunker and among political ghosts, the caudillo has returned to violence, the only weapon that has always been successful,” said a comprehensive report by the French weekly Le Nouvel Observateur.

Agur Franco, goodbye to Franco?

Many cartoons have been made of Francisco Franco Bahamonde, but it will surely be the best of all of them Autobiography of General Franco, by Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. In the Plaza de Oriente of Madrid the paranones of the elderly were brought to the literature, who was unable to pronounce two sentences in a row: “It was repeated. Again the Plaza de Oriente and along with me Prince Juan Carlos, protecting the challenge of Spanish sovereignty both in life and in death, as a straight tree that I have helped to grow well”.

Perhaps these words are the ones that best explain that on November 20, 1975 Franco died, but that Franco was still alive. This was written with the blood of the workers poured into the sidewalks of Vitoria in 1976.

Hilabete eskas Izarreko langileak gure esplotatzaileei (kapitalistak), bere zakurrei (diktadura, guardia zibilak...) eta sindikatu bertikalari aurre egin geniela. (...) Denok gara lekuko hainbat lankide postuz aldatu dituztela bizitza ezinezko egiteko asmoz eta beste langileentzako etsenplu izan dadin (...) Zertarako balio digu hamabi eta hamalau orduz lan egitea nekez bizi bagara? Ez dugu gutxieneko formazio kultural bat hartzeko denborarik, ezta gure emazte eta seme-alabekin lasai egoteko ere. Lortzen dugun bakarra da gure esplotatzaileak aberastea, baina bestetik, biziraungo badugu, ez dugu beste erremediorik orduak sartzea baino. Hala ere, denok ados gaude gizonak bizitzeko ez duela makina bihurtu beharrik. Gure borrokak izan behar du zortzi orduko soldata duina lortzeko, gure familiekin egon ahal izateko, eta ordu estrak sar ditzatela beraiek! Deia egiten diegu Zornotzako langileei adi egoteko, eta Izarrekoei prestatzen hasteko, honek ezin du horrela segi.

1975eko udaberriko afixa anonimoa

(Lazkaoko Beneditarren Artxiboa)

Aurrera dijoakigu inoren eta batipat emakumeon gustokoa ez den «Emakumearen Nazioarteko Urtea». (...) Emakumezko askori lotsa eta amorrazioa eman dio gizonezkoek ezarritako urte polit honek. Hobe litzateke —dio zenbaitek— «gizonezkoen aitormen urtea» izendatu izan balitz, beren probetxurako eratu eta gordetzen saiatu baitira egoera hontaz. Damu dezatela eta hemendik aurrera saia besteen eskubideak arretaz errespetatzen.

Dena den, neure uste apala zer nolakoa den esatera noa. Hauxe da: Nahiz eta askok irrifar desitxarotsuaz hartu izan urte zistrin hau, bertatik emakumearen onerako zerbait ateratzea gerta daiteke. Esango nuke, urtearen haseran baino jende guttiago dela gaur, emakumearen egoera desberdinaz konturatzeke dagoenik. (...)

Ez egile, hartzaile eta jasaile baizik izan den emakumeak, oraindik ere puska batean jasan beharko ditu amodioa, legeak, familia, politika, gudua, lana eta beste eguneroko zenbait zapalkuntza, gizartea dezente aldatzen ez den bitartean behintzat. Bainan inor gutxik pentsatu eta esango du horrela behar duela izan eta hori dela zuzena. Zerbait da.

Esan dezagun, bukatzeko, gizartea bera dagoela atzeraturik. Ez dagoela prest pertsona den emakumea bere bizitza-maila guztietan onartu eta egokitasunez tajutzeko. (...) Horregatik gizartea erabili eta mugiarazten duten neurri berean dago gizonezkoen eta emakumezkoen eskuetan «Nazioarteko Urte» honetan egin behar dena egitea.

Miren Jone Azurtza

(Zeruko Argia,1975-04-27)

Bereziki 1975etik aurrera, ikasle kopuruak gorakada oso handia izan zuen. Gipuzkoan, konparaziora, 1974-1975 ikasturtean 1.607 ikasle izan ziren, eta 1976-1977 ikasturtean 11.454. Bizkaian ere gorakada oso handia izan zen, (12.144 1976an) eta motelagoa gainerako lurraldeetan –handia Araban eta Nafarroan (1.547 eta 3.338 1976an, hurrenez hurren), hala ere, batez ere hiriburuetan kokatuta–, han mugimendua bera beste tamaina batekoa izan baitzen. (...) Ikasle uholde horrek, ordea, arazoak, desoreka eta zailtasunak ekarri zituen, ez zegoelako eskaera horri behar bezala erantzuteko behar adina irakasle, azpiegitura eta baliabide.

Mugimendua gehiago egituratzeko saioak garai hartakoak dira, eta 1974-75 ikasturtean sortu zen, adibidez, Gipuzkoako Gau Eskolen Elkartea. Bizkaian ere Alfabetatze Batzordea eratua zegoen. 1976an bi herrialdeetako gune horiek Alfabetatze Euskalduntze Koordinakundea sortzea pentsatu zuten.

Dabid Anaut

(Euskararen kate hautsiak, 2013)

Irailak 27, krimenaren +42. urtea. Gezurra dirudi Bartzelona urrunean abokatu zahar bati eztarria korapilatzea, euskaldunok espektakulutan entreteniturik gabiltzan bitartean.

Tramitera ere ez dute onartu auzitegiek eskaera. Azpeitiko Udalak eta familiak frankismoaren krimenen kontrako Argentinako kereilara batuko dute kasua.

Haren hilketaren erantzuleak zeintzuk diren argitzea eta horiei ardurak eta erantzunkizunak eskatzea nahi dute. Horretarako, sumarioaren kopia bat eskuratzea nahi dute. Bidea "zaila" izango dela azaldu du Angel Otaegiren familiako abokatuak, baina "merezi"... [+]