- The neighbours of Usansolo are called to a referendum on 23 November in the Upper Chamber. At the moment they will have to say whether they want the Galdakao district to become a municipality. The result will not be legally binding, but it will be politically significant. The Provincial Council of Bizkaia is ready to amend the rule that prevents the creation of new municipalities since 2012 if Usansolo manifests its willingness to count on it. This would be the 36th anniversary of its founding in the Basque Country since 1983. In the meantime, what will happen in Igeldo?

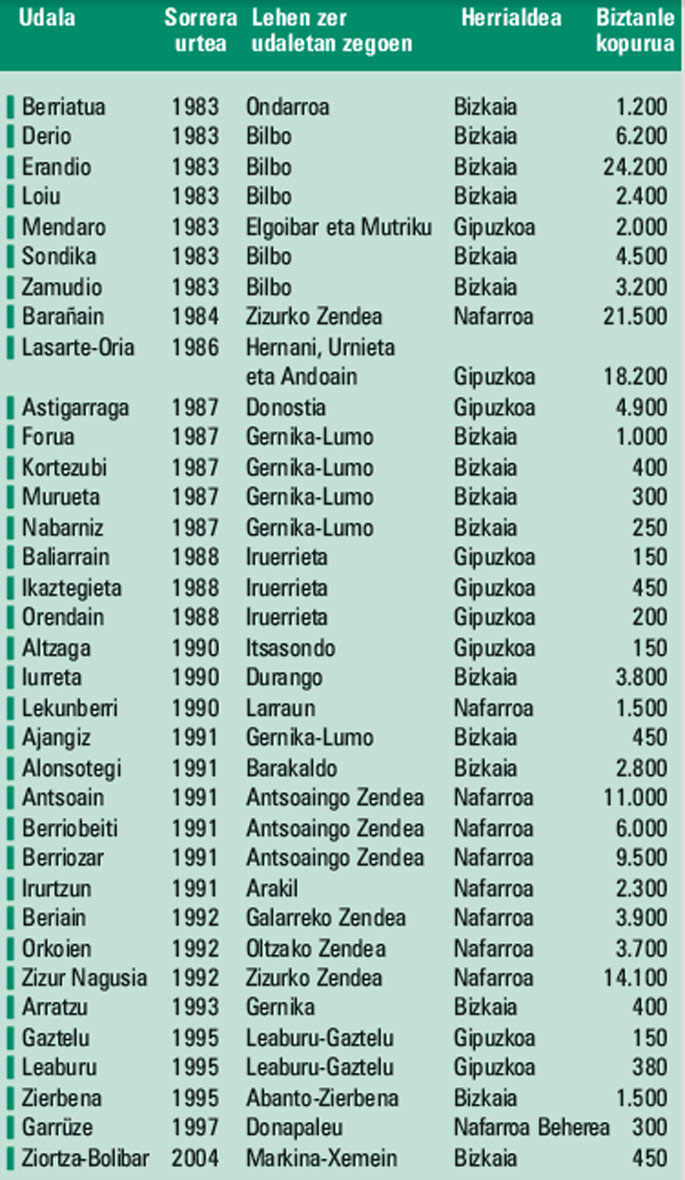

To believe in Wikipedia, Euskal Herria has 685 municipalities. Of these, 35 have been created in the last three decades, as explained in detail in the table that will show you after the page has passed. It's very likely that Usansolo, the Galdakao neighborhood today, will join the list next year, or maybe the next year. These procedures, you know, take time.

Without fear of being mistaken, it can be said that the will of the majority of Usansolo’s neighbours and neighbours, who must ratify in the non-binding consultation on 23 November, is the creation of a city hall. Proof of this is that the Usansolo Herria platform won the most recent municipal elections in the Usansolo district. His electoral programme focused on a single word: deannexation.

But the popular will is not enough, otherwise Usansolo would have had his council a long time ago. But on this occasion, it seems that the obstacles that for years have prevented the segregation from being carried out are about to disappear, given the provision shown in recent months by Itxaso Atutxa of the Bizkai Buru Batzar, the MP of Bizkaia, José Luis Bilbao, and the Mayor of Galdakao, Ibon Uribe. The substantial discrepancies between the City Council of Galdakao and the Usansolo Herria platform in terms of the procedure will hardly prevent Bizkaia from having another town hall if the above three keep their word.

Once Usansolo of Galdakao has been dismantled, it would only be a solution to the case of Igeldo, now in the hands of a judge, to close the municipal map of the Basque Country, at least until there is a profound reform of the administrative structure, which could happen in the French State, but that is another story.

The Outbreak of Exion in the 1980s

The Coordinadora de Pueblos por la Desanexión was born in the mid-1970s, primarily driven by the citizenship of Erandio. One of the founders of this movement, Txetxu Aurrekoetxea, has pointed out to us that the main promoters of the coordinator were the villages of the Biscayan valley of Txorierri (Erandio, Loiu, Derio, Sondika and Zamudio), and thanks to its initiative other towns of Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa joined: Iurreta, Mendaro, Lasarte…

The five villages of the Txorierri were forced during Franco to join Bilbao. For this, according to Aurrekoetxea, the dictatorship had two reasons. One, ideological: Great Spain needed big cities. The other reason also has to do with grandeur, but it is more prosaic: the need for land for the execution of urban plans. The case of Bilbao was not the only case in the Basque Country, but it was the most significant.

The development coordinator largely achieved the objective, which is obvious. On 22 December 1982, the Basque Government signed the decree for the disengagement of Bilbao from the five municipalities. It was the only such decree given by the Basque Government, and all those who have come from then on have been at the hands of the deputies. By the way, let us say that this massive deannexation was not the only one; in 1987, four peoples separated simultaneously from Gernika. The story is similar to that of Bilbao. The disengagement of many others occurred individually, and in some cases the City Hall was set up, but it could not be said that there was deannexation. Between 1983 and 1993 30 municipalities emerged in the Basque Country.

None in Álava, one in Iparralde

It is worth mentioning that in the period indicated, and later, there has been no deannexation or segregation in Álava, and that in Ipar Euskal Herria it has been unique. No distinctions, no requests. As far as the North is concerned, one problem must be taken into account by the French State: the tremendous municipal inflation. Almost half of the municipalities across the European Union are in France (about 36,000! ), and Paris wants no more. There is no law prohibiting the creation of new municipalities, but there is a general principle on possible lawsuits, the application of which falls to the prefects: to respond negatively to petitions.

The fact that the wave of dismemberment of Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa did not reach Álava has its explanation, according to the professor of Geography of the UPV/EHU Iñaki Moro: “Álava is the territory of the three territories of the CAPV that has maintained the most communal lands, which has allowed small entities to maintain their management capacity in different areas”.

No lack, no desire. Without going back a long time, the Scottish and Catalan cases have demonstrated in the debate on sovereignty that the right to self-management is increasingly important, along with traditional identity elements. If so in the case of whole nations, let us not say anything at the municipal level. As in Usansolo, in Igeldo, the attention given to them by the “metropolis” is scarce in the discourse of those who want to differentiate themselves from one of the main pillars. And yet, in the processes of deannexation there is an identity component, often given by physical distance or historical tradition.

Two steps to implement what started in 1983

The wave of desannexation and segregation of the 1980s would have brought peace in the municipal distribution of Euskal Herria, if there were no three cases to be resolved: Igeldo, Usansolo and Itziar. The third is on track, because the Itziar themselves, tired of the obstacles that had been put in place by the City of Deba and the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa, gave way in the early 2000s. Leaving aside the desire to obtain the City Hall, a few years ago began the struggle to turn it into a municipal district within Deba, and although it is not to everyone’s liking it seems that the goal is yet to come.

To understand the persistence of the conflicts of Usansolo and Igeldo to date, it is essential to explain some legislative changes. In the CAPV, the Deputies are responsible for the creation of new municipalities. It has rained a great deal since the first de-annexation of 1983, and a number of foral rules have been created to establish the conditions for carrying out segregations – the word “de-annexation” will not be found in these rules. In Usansolo and in Igeldo they complained that both in Bizkaia and in Gipuzkoa the rules have been created ad hoc to hinder this claim.

José Ignacio Galparsoro of the Itxas Aurre de Igeldo Association reminded us that in 1990 they began to study the possibility that some of Igeldo's neighbors would differ from Donostia-San Sebastián. Four years later there was a popular consultation in which the majority was in favour of setting up a city hall. “Shortly afterwards a new Foral Norm was elaborated, in an emergency act against Igeldo, which has two requirements that we cannot meet: one, having at least 2,500 inhabitants [has about 1,000 inhabitants], and the other agreeing with the City Hall of Donostia, but the City Hall has never wanted to accept the will of the Igeldotarras”. The rule currently in force is that of 2003 and maintains both conditions.

In 1995, Igeldo’s proponents of segregation argued that their procedure had been initiated prior to the creation of the standard, and the conditions prior to it should be imposed. In these years, both the High Court of Justice of the Basque Country and that of Madrid have given them the right, but that has not served them: In 2010, the Deputy finally dismissed by decree its request for disengagement, in accordance with the conditions in force in 1986.

Total ban in Bizkaia since 2012

Until 2012, the foral regulations of Gipuzkoa and Bizkaia were very similar, including the requirement of 2,500 inhabitants. But in that year, the General Boards of Gernika adopted a new rule, still in force. This rule prohibits the creation of new municipalities in Bizkaia. Monika Mena, of the Usansolo Herria platform (UH), believes that the aim of the change was very concrete, “since the only process of deannexation that is taking place in Bizkaia is ours.” The UH tried to have the rule include a transitional provision opening a deadline for the execution of procedures already initiated, but its objective was not achieved.

If this rule did not exist or the above provision was added, Usansolo would have the opportunity to separate from Galdakao as it complies with all the requirements set out in the previous foral rules. It has about 5,000 inhabitants, is far enough from the center of Galdakao and is economically viable, according to a recent study by the UPV/EHU. In fact, the most surprising thing is that it is not yet a city hall, given that in 1988 efforts began to achieve this goal.

Mena explains that in the early 1990s, three studies were carried out to measure the viability of an independent Usansolo. Both sides were in favour, but the third party’s refusal paralysed the whole process. The negative test was performed by a law firm, which has a close relationship with the PNV, according to the same source.

The result was a 15-year impasse. In 2011, the desire for development is strengthened and formed in the UH platform. In the municipal elections they obtained an unexpected result: two councillors and a large majority in Usansolo. The following year, the Council imposed a ban on the creation of new municipalities. At the moment, the UH has appealed the new foral rule to the Supreme Court.

Iñaki Lasagabaster, professor of administrative law at the UPV/EHU, has given us his opinion on this rule: “In fact, I do not think it is a bad thing that such a rule should be established if a request for disengagement is not foreseen. It also serves to rationalize administration. Another thing is to put an end to a process that is already underway, which would be a measure against citizenship. The Member has realised that the situation cannot go on like this and has announced that it will make adjustments to the regulations in order to respect the will of the usansolans”. Lasagabaster is right. In addition to José Luis Bilbao, the PNV and the City Hall of Galdakao have expressed their willingness to initiate a process that could lead to the segregation of Usansolo, in the case of the institutions, and to support it, in the case of the training.

The first step in this process would be the modification of the foral rule, and the last, the realization of a popular consultation. To do so, they will only be trained in the referendum that the UH has called for on 23 November this week. Question: “Do you want Usansolo to be a town?”

The results will have no legal value, but they will have political value. “In Galdakao, in Bilbao and in Madrid we want to hear what Usansolo wants,” says Mónica Mena. The Mayor of Galdakao, Ibon Uribe, said that he is not going to obstruct the referendum, but he is not going to support it either, because the procedure should be another. The confrontation between the UH and Uribe has given much to talk about in the last askeos, but it does not seem that this could hinder the creation of the 113 Biscayan municipality.

A town that was city hall for two months

On the road to Bizkaia 113.enera, and in Gipuzkoa 89.aren, birth has been interrupted. The events that took place in Igeldo last winter are well known: after the majority vote on segregation by popular consultation, the Provincial Council ordered by decree the creation of the new City Hall of Igeldo, but in February of this year the High Court of Justice of the Basque Country suspended that decree, under the recourse of the City Hall of Donostia-San Sebastián. Igeldo, who after two months as a city hall was once again a district, and the members of the association Itxas Aurre, as well as the majority of the citizens, are waiting with regret for the judge’s final ruling.

Why in the case of Igeldo the PNV does not have the same attitude towards Usansolo?, Itxas Aurre has been asked publicly. Response from Sabin Etxea: “In Usansolo and Igeldo it is clear that there are two models. One, the one carried out by the Council of Gipuzkoa, that of taxation, in violation of the laws that have been given in the JJGG and in misleading Igeldo with an invaluable consultation. And the other, the one proposed by the PNV in Usansolo: to hold a referendum within the law.”

1983ko urtarrilaren 1ean Bilboko bost auzo desanexionatu zirenetik, beste 30 udal sortu dira Euskal Herrian, ia denak 80ko hamarkadan eta 90ekoaren hasieran. 1994tik bost udal berri besterik ez dira eratu, eta bakarra XXI. mendean: Ziortza-Bolibar.

35 udalerri berrietatik, hamasei Bizkaian daude, bederatzina Gipuzkoan eta Nafarroan, eta bat Baxenabarren. Betiere bereizketa baten ondorioz sortutako udalez ari gara, ez elkarketaz sortutakoez. Bereizketa horietako asko desanexioak dira, baina badira zatiketak ere, tamaina bertsuko udalak eman dituztenak. Leaburu-Gazteluk, esaterako, erdibitzea erabaki zuen 1995ean; zazpi urte lehenago, hiru zatitan banatu zen Iruerrieta, Gipuzkoan ere bai.

Nafarroan, udal berri gehienak Iruñerriko zendeen zatiketaz jaio dira. Zendea esaten zaie Iruñea inguruan sortutako bost herri bilguneri (udal izaera dute): Zizurkoa, Oltzakoa, Galarrekoa, Izakoa eta Antsoaingoa. Azken hori ez da existitzen dagoeneko; 1991n, Antsoain eta Berriozarrek zendea utzi eta udal bilakatu ostean, geratu ziren gainerako herriek Berriobeiti eratzea erabaki zuten.

Bitxia da zendeetatik bereizi diren udal gehienak, behin sortuta, zendea bera baino biztanletsuago izan direla. Esaterako, askoz populazio handiagoa dute Barañainek eta Zizur Nagusiak euren jatorrizko udala den Zizurko Zendeak baino, hura ez baita 4.000 biztanlera iristen. Barañain, izan ere, zerrenda honetako udal populatuena da, Erandioren ostean. Aldea hain nabarmena ez bada ere, gauza bera gertatu zen Beriain eta Orkoienen kasuetan.