The Navarro communist who led the biggest attack on Franco

- In October 1944, 3,000 guerrillas entered the Pyrenees Valley, with the objective of establishing a provisional republican government. The attack was designed and directed by Jesús Monzón Reparaz (Pamplona, 1910-1973) and paid dearly for his decision.

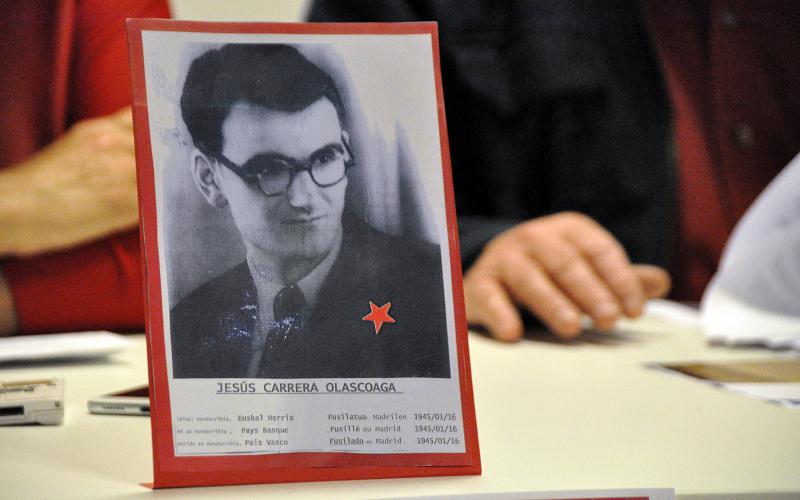

In Pamplona there are no streets, no houses of culture, no libraries bearing their name. Moreover, there are few Navarros who know the anecdotes of this man. However, this communist born in Pamplona, Jesús Monzón Reparaz, had in his hands the key to change the direction of our contemporary history. Thanks to him there was the most relevant attack on Franco during the dictatorship: Invasion of Aran Valley. For reasons that are still unknown, the initiative failed, and the Franco regime and the leadership of the communists, led by Santiago Carrillo, were thrown at it.

A pact between friends

Very easily, Jesus Monzón could be the protagonist of an adventure novel. The Navarro historian and journalist Manuel Martorell (Elizondo, 1953) has been one of the few researchers who has analyzed in depth the rugged biography of this shareholder. We met him in the Plaza del Castillo, a place where the importance of life or life on the Monsoon route would have been important: “Pamplona – says Martorell – would then have about 40,000 inhabitants, which currently has Tudela. As one might suppose, most of the young people who at that time participated in political issues would get to know each other. Well, these young people had the ability to put the personal and the affective before the political ideas.”

When he makes this statement, Martorell tries to reach an agreement that several young people from Pamplona of different ideologies reached an agreement. Among the attendees were Jesús Monzón himself, the lawyer and military Tomás Garicano Goñi, Republican Ignacio Usechi, CEDA member Ignacio Ruiz de Galarreta or the nationalist lawyer Estanislao Aranzadi. This agreement was based on the commitment to provide assistance to those who were in danger after the war that was about to begin. According to Martorell, those behind this decision showed “the highest intellectual attitude”: “You can often lose friends for political reasons and, paradoxically, over time, political parties can change their views on the issue that caused the discrepancy. Of course, politics is very important, and what happened at that time, very serious; but those young people saw the need to maintain friendship, because they didn’t know how things would end.”

During an investigation into the Carlist movement of Navarros journalists, his passion for investigating the past of Monzón manifested itself in full effervescence. Among the thousands and thousands of pages that passed through his eyes, an anecdote stood out. The protagonist, the father of the Navarro politician Jaime Ignacio del Burg: “On July 19, 1936 he saw Jesús Monzón hiding in a portal of Avenida Carlos III de Pamplona. From Burg he did not intentionally denounce Monzón.”

Before the outbreak of the war, the construction of the Ensanche and the works of the new Navarros railways, in neighborhoods like the Rotxapea, was giving birth to the left movement of Pamplona, and Monzón, as soon as finishing the studies in Madrid, became the leader of this movement. The war began and left Pamplona and occupied the post of government delegate in several cities, until, with the victory of the nationals, he took the plane in Alicante and fled with Dolores Ibarruri to Orán (Algeria).

During all these years, the chain of favors among friends was not interrupted. Dressed in Capuchin friars, Monzón was helped to flee from Pamplona, in the hands of the Francoists. And conversely, being the government’s delegate in Alicante, Monzón helped Antonio Lizarza, creator of Leitza’s requetés, leave Valencia.

The Exile

It is 75 years since the beginning of World War II. The struggle was the failure of fascism. Along with this, the hope of overthrowing the dictator Franco took hold. After Jesús Monzón assumed responsibility for the restructuring of the Communist Party, in order to take advantage of the situation that had just been born, he drafted a plan to invade Val d’Aran (Lleida). Thousands of guerrillas who fought in France with the allies would have taken this isolated valley, sowing on the peninsula the seed of revolt, in order to receive the support of the allies.

Contrary to what most members of the Communist Party thought, Monzón saw differences between the ideas of Carlists and fascists. He was convinced that in the Basque Country and in Catalonia many Carlists did not see Franco with good eyes: “For Monzón,” says Martorell, “II. The end of the World War offered an unbeatable opportunity for the countries that dominated fascism to join the anti-Francoist movement. For this movement to succeed, however, it was necessary to reconcile the victors’ democracy with the criteria. In the new unity government which would be set up, there would be Carlists which corresponded to the United Kingdom, for example, with Communists and Anarchists. As the writer Almudena Grandes says, the allies would have acted differently, without disillusionment, if in the valley of Aran a government had been formed that would take back the plurality of society then”.

The issue of the invasion of 1944 is still an unclosed chapter. What is clear is that: That Jesus Monzón was condemned to ostracism, and that Carrillo took advantage of defeat to take command and clean Monzón's hobby. Shortly after the guerrilla stepped back from the Aran Valley, Carrillo called Monzón to meet in Toulouse. Monzón, on the other hand, made a stop in Barcelona. This resolution had certainly allowed him to keep his life, since the people he called in those cases did not come to the appointment, but had been murdered by his own party colleagues.

The Barcelona police arrested Monzón in the house of a member of the Joventut Combatent group, who supported the PSUC guerrillas. It is surprising the courage shown by Jesús Monzón, following the war, leading the invasion of Arán and restructuring the PCE in France, to travel underground in Madrid and Barcelona: “What they were fishing in Madrid was shot in a few months,” explains Martorell. You have to have a heart! As journalist Manuel Vázquez Montalbán said, Monzón was a ‘moral athlete’ of history. He risked himself to gain little or nothing.”

Monsoon was not sentenced to death. According to some testimonies collected by the Foral Police, Thomas Garicano survived death thanks, among others, to Goñi's mediation. Martorell, after 30 years in prison, also acknowledges the intervention of his friends: “Many of these young friends were in the army’s legal service. And they forcibly had to move the strings to avoid the death penalty. Perhaps they used the strategy of letting time go so that conditions would soften. The machine was still alive and there were executions, but the war had ended and the regime, little by little, was showing the will to open.”

After 13 years in jail, with the work doors completely closed, Monzón flew to Mexico to meet his wife. In the desert of France he separated from Aurora Gómez Urrutia, but they were left free and then reunited. Monzón was already an anonymous person, far from the front line of politics. Subsequently, numerous party colleagues would denounce their historical injustice in the history story, such as Manuel Azcarate or Jorge Semprún.Upon her return from Mexico, after residing in Mallorca, the

Navarre found death at her home in Pamplona/Iruña. Less than 30 people met at the civil funeral in the Berichitos cemetery. Santiago Carrillo participated in one of the last events, and Manuel Martorell approached him to ask him about Monzón. The response was lonic: “Yes, that’s what we should talk about.” But Carrillo would take everything he knew to the grave.

Jesus Monzonen bizitza gutxik ezagutzen badute, are ezezagunagoa da Badostainen jaiotako Uriz ahizpen jarduna. 1930eko hamarkadatik aurrera, Pepita eta Elisa Urizek hezkuntza sistemaren aldaketa bultzatzeko eta haurren eskubideak sustatzeko lan beltza egin zuten. Sarrigurengo Eskola Publikoak, bederen, Pepita Urizen izena eramanen du, Nafarroako Gobernuak izendapenari oniritzia ematen badio.

Bada, Manuel Martorell konbentzitua dago, Aran bailarako inbasioan, Pepita Urizek emaniko informazioa erabakigarria izan zela: “Bi ahizpak Magisteritza Eskolako irakasleak ziren. Pepita Urizek Batec (taupada, katalanez) berrikuntza pedagogikoaren aldeko taldean parte hartu zuen, eta García Lorcak ezagutarazi zituen ‘misio pedagogikoetan’ aritu zen. 1933an eta 1934an Pepitak Lleidako iparraldean isolaturik zeuden herri gehienak bisitatu zituen Célestin Freineten teknika pedagogikoa zabaltzen. Eta Lleidako iparraldean zer dago? Aran bailara”.

Vichyren gobernu kolaborazionistaren eta alemaniarrek okupaturiko zonaldearen artean zatitua zegoen Frantzian, Uriz ahizpak Parisko Alderdi Komunistako nukleoan zebiltzan. Hauekin Manuel Azcarate politikariak kontaktatu zuen inoiz, bera bi aldeen arteko lotura baitzen. Bat-batean, ahizpek Frantziako hegoaldera egin zuten: “Monzonek berak –dio Martorellek– 1944 urteko nortasun-agiria zeukan, Foixen egina, Pirinioetan. Zonalde horretan prestatu zuten Arango inbasioa. Bada, Parisen sarekada bat izan zela-eta, Uriz ahizpek Frantziako hegoaldera ihes egiteko modua izan zuten. Eta ziur naiz inbasioa antolatu zutenek zonaldeari buruzko informazio zehatza bilatu zutela, baita horretan Pepita Uriz ibili zela ere, Monzonekin batera. Zoritxarrez, oraino ezin izan da halakorik frogatu”.

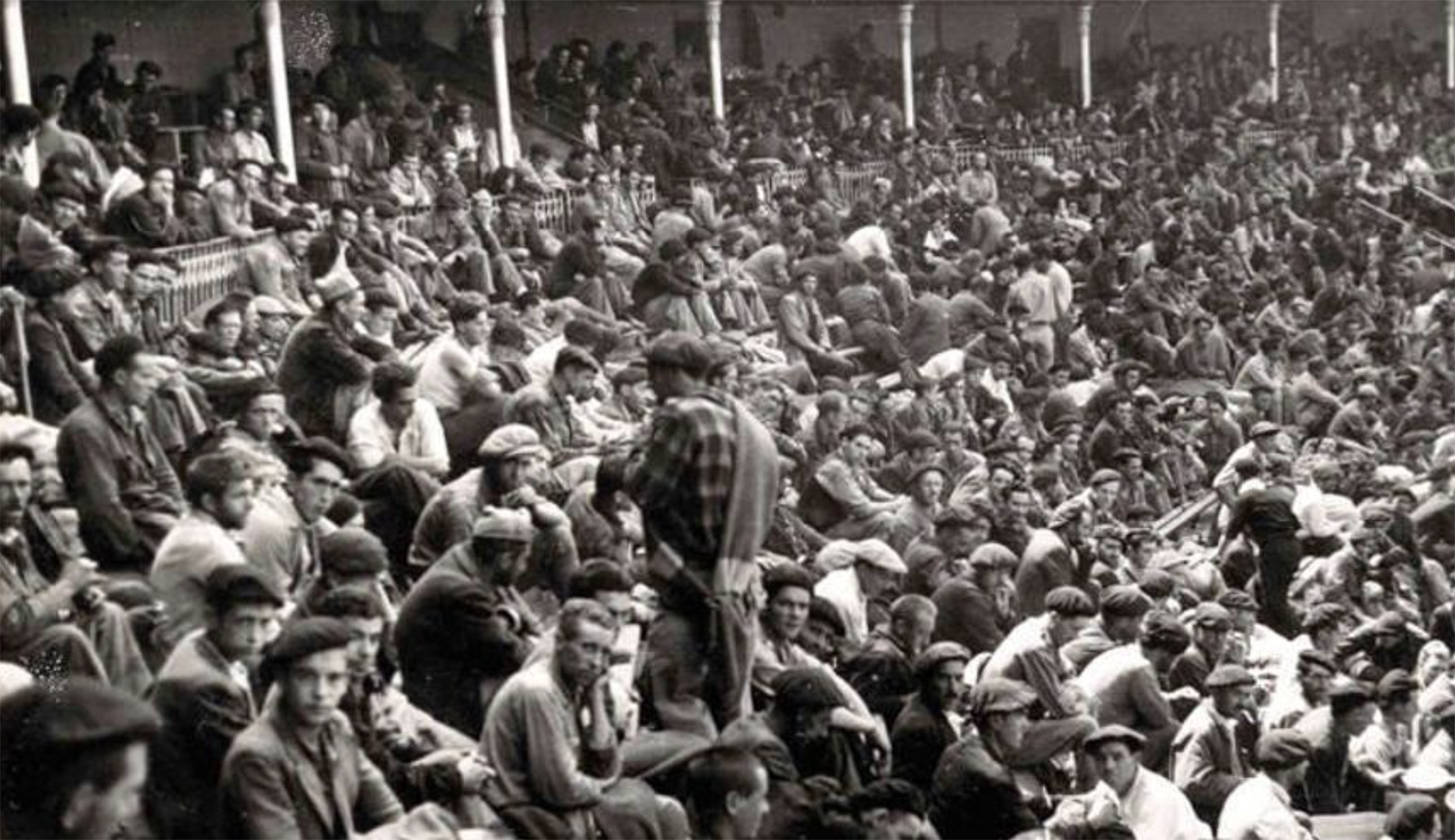

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]