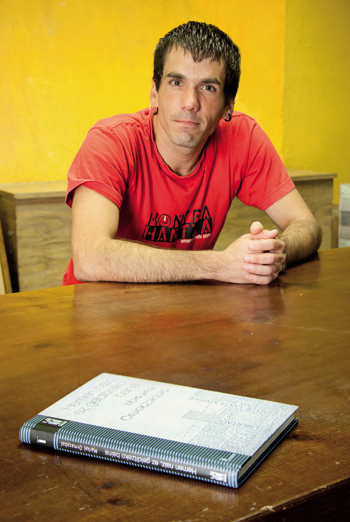

- Markel Ormazabal (Donostia-San Sebastián, 1982) has been imprisoned twice for his work in the youth eta movement. He has studied Sociology and has written his first book among barrotes: Here I am not to stop but (Txalaparta, 2014). The book goes beyond the prison chronicle, and it speaks to us beyond the book, the writing and, above all, the prison.

When did he arrive in jail?

I've been in two eras. First, in 2002, I was arrested in a police raid on street violence. After three days of incommunication and suffering from torture, I was received for a month at the Young Module of Alcalá Meco. The second prison was issued between 2007 and January 2013, in the summary opened by Jarrai-Haika-Segi. In the past, the father was also arrested in case 18/98.

You have emphasised that, even if this prison is present in our history, we know nothing about it.

In the presentation of the book I said the anecdote: one year after entering the jail, a woman appeared in the neighborhood that we know in every mess for the rights of the prisoners, with two bags of food in her hands, to take her to her son. The woman did not realize that since the time of Herrera de la Mancha, almost 30 years ago, it is forbidden to introduce food abroad.

He has taken advantage of the references and references of the prisoners. What are the collection work and the creative process like by the cell?

One prisoner said that the prison resembles the funnel. In the patio we often talked about the food, we got to jail and in the first days you want to eat a chop or a cod, but over time the funnel leaves getting thinner and in the end you have two dignified fried eggs. With creativity as well: when I got to jail I had great ideas, comic book, book of verses, poetry… But in the meantime I was collecting texts about jail and after years I realized I had a lot of information and I didn’t know what to do. That's why the book is more collage than chronicle. There are many references, but not all. The record, because of cell changes, I lost a lot of papers.

You also collaborated with Irutxuloko Hitza. Does writing help escape?

Inside the prison each can look for his or her disciplines, study, sport, writing… but the prisoner he or she writes puts his or her time in jail and practices that time to flee.

He previously collaborated in Irutxuloko Hitza. Continuing to write from the inside allowed me to continue devouring information about San Sebastian. I am very grateful to you.

Can you write from jail without ever having it inside?

Probably not. The best texts written in prison have been written by prisoners, both creative and academic. I remember Professor Pedro Oliver. Condemned in his day for injunction in the prison in Pamplona, he is currently probably the professor of the Spanish State who has carried out more research on the prison situation.

The book deals with what the prison penal system brings to society.

Yes. Jail is a social aberration, it serves as a rug: as long as we don't see the dirtiness of society, we're happy. That is why we need to make a deep collective reflection about prison. I have always known the discussion of whether or not prison is on the table. But it’s not the same to shout “prisons for their owners” as “break them.” Hence the eternal question: What will we do with criminals when we are once a free people?

Is a people without a prison possible?

I'm sure so, because Euskal Herria is a very small society. I believe in the capacity of small peoples to form community and Euskal Herria fulfills all the elements to work other experiences. We need people to think about it.

In the book, Iratxe Retolaza has written an analysis of the weight of prison literature in the Basque Country. Have you had more echo here than outside?

More than in the villages around. The prison literature has been able to put on the table a reality of the people, but also what has been written should give us what to think. These are very political texts. Sarrionandia makes a very clear line there, not so much because of the texts, but because he goes from being a writer to being imprisoned on the street. The same is true of Mikel Anza today, despite the fact that this is a different case for the years that went by.

However, the relationship between prison and the Basque literature is very old. If you look at the 1936 war, Jokin Urain did a great job in the book Ez dago etxean. Later, in the book Linguae Vasconum Primitiae of 1545, Bernart Etxepare published several verses written for the first time in Basque from prison.

More than a personal testimony, the reader reflects the collective experience.

Yes, and most of the prison literature that has been written here has been written from that perspective. There are exceptions such as the Days of Iñaki De Juana or the Kitchen Llave of Josu Urrutikoetxea. Even though they are texts written from me, they do not delve so much into the body or into the way each one is in jail; it is more the collective contribution.

Lately there are many books in which musical reviews appear. You have closed each section with a song.

The use of music, besides being a feature of the melomaniac, is an exercise related to the disability of the jail. Access to music in prisons has long been banned. I had the opportunity to buy music and listen to some of the works that had just been produced in Euskal Herria, but it is not usual. It's the songs I've been able to get in the last few years that I've been talking about in the book, older ones, that I couldn't even feel like I'm missing or listening to.

I've been lucky to buy, but I haven't been able to create music. I was rejected from all requests for instruments in the name of security. I've told in the book that The Clash's have done "A Prisoner, a Guitar" campaigns in London to put the instruments in jail, but the difficulties are enormous.

The title of the song by Lisabö, Hemen naiz, ez gelditu baina. But the shadow of the jail remains in the prisoner.

Yeah, that's what I mention with Sarrionandia's poem at the beginning of the book. “The mind of those who have been imprisoned not to go back to jail,” thinking about who will then be in the cell that you left… While in jail I read the poem over and over and said, “It’s impossible, out of here and what the hell is going to give you back your mind!” But I understood what Sarrionandia was saying, a year after I got out on the street. Being a prisoner cannot be extirpated, it remains there, even if we do not stay. n