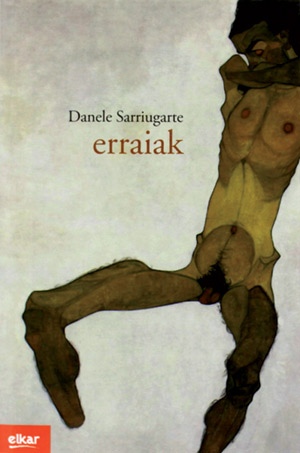

This book, as you can read in the back cover, “part of a painful couple rupture.” The protagonist, through the inner monologue, throws his thoughts and feelings to these pages in a long vomit. Then, if we look at what has been thrown away, we will find some reflections on the power relations, both within the family, with the crews and friends, as well as on the personal situation with the people and the community. The weight of romantic love, affective dependence and sex and desire games and fights will also be spread here and there. Ties, chains, loneliness and need to flee. Parral, Zuloa, Berlin, Denver, Beefeater, Toblerone, Nirvana or Anari are also there. Charles Bukowski, of course.

“If Hank Txinaski (Euskal) emakume (gazte)a?” This question could be the title of this critique, and also the guiding thread of this book. This reading reminded me of an interview that took place a few years ago in a bar in Ea one night in July. How can a feminist Bukowski like? How can a feminist read and enjoy the scrolls of a misogynist? I believe that this book can be an attempt to answer that naughty question (even to the one that was launched at the beginning of this paragraph).

Iban Zaldua said in the preamble to Uxue Apaolaza’s first work (I refer to himself) that there you could read that penes got hooked. However, at the beginning of Danele Sarriugarte's first job, the little one softens and becomes wet, and when she approaches the end, the protagonist says she enjoys looking at her lover's face when she drills the anus. This criticism could also have the title of “Knitting Letters”. In recent years Basque writers are moving their bodies to the foreground and Sarriugarte’s work gives continuity to this trend. You bowels. The protagonist listens to the heart, the liver, the casings, the muzzle. We can read “the body is the end and the tool.” The embodied subject brought here by Mari Luz Esteban speaks to the reader. The social role that has touched him leaves the narrative pages open, between the present and the memories, and you can read the sounds of those who look at the torn skin to break those chains.

Joan Tartas (Sohüta, 1610 - date of unknown death) is not one of the most famous writers in the history of our letters and yet we discover good things in this “mendre piece” whose title, let us admit it from the beginning, is probably not the most commercial of the titles... [+]

ilbeltza-(1).jpg)