"Life can be interrupted if you remember too much the horror."

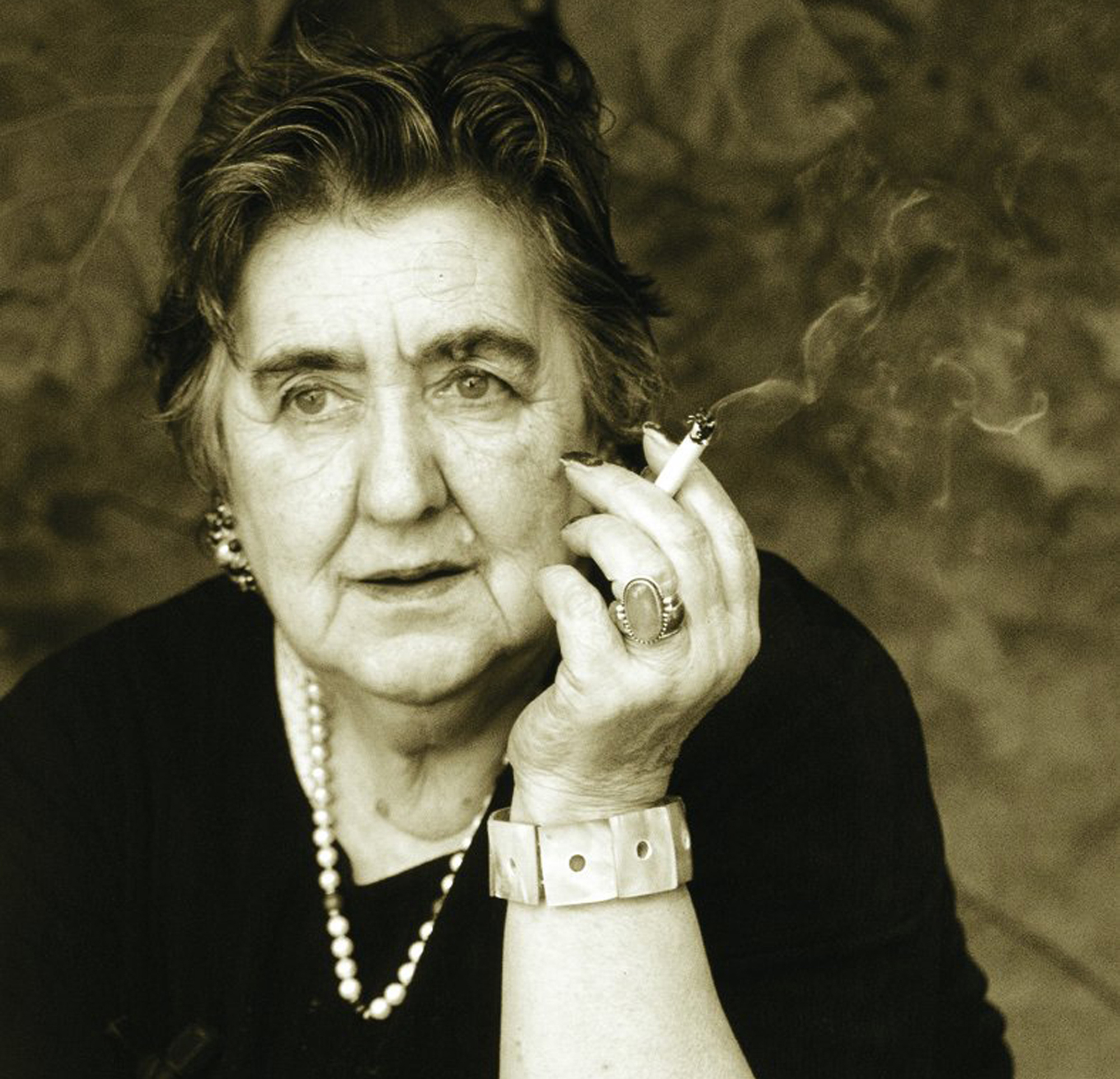

- The sky has collapsed since Igela Publishing House unveiled Lorenza Mazzetti, director of film and writer, among others. A simple and sweet woman who has just turned 86 is on guard and, after the terrible tragedy she has experienced, is still amazed by her mood.

The mother of both died in giving birth to the twins Lorenza and Paola. His father, by accident, a few years away. Having been orphaned for the first time, the two children were greeted by their uncles, Nina Mazzetti and Robert Einstein, in a village next to Florence, called Il Focardo. The Nazis, when they retired from Italy in 1944, went to search for their uncle and, upon learning of the flight, took their aunt and their two cousins to a room where they were shot to death. Uncle Robert committed suicide in 1945. Orphaned for the second time. Lorenzo and Paola were named heirs of all their property. Around 1954, Lorenza moved to London to continue his studies. The guardian of the twins wasted the inheritance that his uncle had left the two sisters and left them without a penny. After the film K and Together was released, it was one of the four signatories to the Free Cinema manifesto. Back in London in the 1960s, the psychiatrist ordered him to write down his childhood experience. For twenty days, with the French writer Guillaume Chpaltine next to him, he wrote a book that would completely change his life.

He lives on the last floor of a house near Campo dei Fiori, next to his sister Paola. It is believed that two years ago her husband, who had been a doctor of the relatives of the partisans, died. Books don't give it much. But he has not complained at all about it.

Campo is going to buy to the market of Fiori, the plaza where the heretic Giordano Bruno was burned. The statue of the heretic is erected at the center of a market of vegetables and flowers. The sky did not collapse before him, but instead was sent to the sky in flames.

When we asked Mrs. Mazzetti where we could see ourselves to interview the light, she invited us home. We're a little nervous, but nothing else goes into the house: “Baschi! Rivoluzionari!” welcomes us – as seen in her books, an older woman who did not have a revolutionary dream in her youth. Did you remember the time when Bruno Grieco, the son of one of the founders of the PCI, had a partner?

We have clarified who we are and we think that Basque youth has something to learn from their experiences and that is why we want to interview them. Hearing this before starting with the questions, he makes the following comment: “I also think they have things to learn, but I didn’t know you would think so.” And we started with the questions.

He has just published his last book, Londinese Journal. Can you explain why you've written it now and what will the reader find there?

These are very old things, because I've had a lot of time to look back and elaborate everything that happened to me. The Londinese Journal ends when I returned to Italy. I went back to Italy and there I had the decadence (“il patatrac”), which had to happen immediately after the tragedy, and which was eliminated, repressed in order to survive. Because life can stop if you remember too much horror.

Can you explain it a little bit?

Yes, because memory can block the heart, petrify the person and leave him as a dead person. So in order to survive, you have to suppress the memory, you have to delete it. That is why I fled from Tuscany to London. London was hell, and that felt good. I wanted to flee from the Tuscan beauty, from the joy, from the happiness of childhood, and especially from the crickets, from the peasants… from everything that constituted the happiness of childhood, from all that happiness these people had given me. So, London was so black, gray -- people didn't speak -- I felt in hell. But I realized that darkness was going well. I was fascinated by that world. It was so different from Italy! There I could live as a rich heir, because my uncle had handed us a great fortune. But from one day to the next, I was left with nothing. I didn't have a penny to pay for it.

You made you completely poor.

Yes, I had to protect myself from the rain. And eat. In addition, my twin sister, Baby, had married a psychiatrist in Italy, and my husband also prevented us from having a telephone relationship, as we both had to learn to live apart. That was terribly hard, because during that time I could go crazy. So at this time of my life, I followed my unconscious, who made me do weird things. But it also guides me to the repressed tragedy.

Your London experience looks like the story of someone who has faced hard difficulties. In the book you say you were in London and you sat near Kafka.

Yes. Interestingly, I read Kafka and felt it was close; the metamorphosis and the process were close to me. Thus, in the Metamorphosis appears a character that sees the outside world as something that does not understand or accept, and that sees it as a monster because it is not like others. What matters is that this young man, who in my film looks like an angel, increases that contrast. Anyway, the truth is that I “stole” the roll machine at the University, and I did it without a single lira. I was dedicated to cleaning dishes, but I wanted to make that film, believing that that way I would form an identity of my own, a portrait of myself, of society. He laughed a lot when he remembered that evil.

A few years ago you said that the situation you lived in London, that of being rich and becoming poor from one day to the next, was beneficial.

Yes, we had a tutor, and when I was in London, I knew that my uncle had wasted all the assets that he had left us and that we wouldn't see a lira. So in a way, as I get rich and become poor, I've done a lot of things that I wouldn't have done otherwise, and I've found my personality. If I had been rich, I would have lived with a pension, and we don't know what would have happened. But I wouldn't become a writer.

You've ever said Heaven comes down on the advice of your psychiatrist.

When I made the film, I didn't know that I would write Heaven collapses, because I was suppressed, erased, deliberately forgotten, which I then counted in the book. It was a therapy to go back to Florence, get sick, because all the memories, intolerable, came back, and the psychiatrist said to me: “You have to face that memory; otherwise, the night and memories will always come back.” Then he said: “Because it is right that you want to forget all this in order to survive. But now that you've survived, the anguish that produces you is your uncle's abandonment and not counting everything that happened, everything that you were given. You've forgotten those people and you have to take them out of the grave of your heart. That's why I wrote Heaven collapses and my dreams, my nightmares, didn't return.

The success was, then, not only literary, but personal.

Yes, of course, but I had to go there, go back there and remember all that. It was terrible, don't believe it.

We have a doubt. The sky collapses in the book, because being an autobiographical, why did you hide the age of two sisters and have twins?

I hid not only my age, but many other things, my uncle's name, my aunt's name, and I didn't tell anyone that it was a tragedy that really happened. Because if I had been able to write a book as an adult person who writes memories, it would have been a very different book, but I only managed to write my childhood memories. And, therefore, this book is very ridiculous and insinuating against it. And it seems it was invented, but the only way I had to deal with that tragedy was to invent a little girl who barely understood anything, because, as an adult, I was going to write a completely different book. However, by making the Baby smaller, I was able to make minor observations, such as that of the bishop. That, for example, is not something a ten-year-old girl can do. Well, I did.

Federico Fellini said he had never read such a funny book. And finally, that someone saw war with another look, which was a new point of view.

Yes, it was new. Indeed, the facts were seen from the point of view of a child who had Mussolini as an idol, because we had Ducea as an idol. For us it was like Jesus. For us were Jesus, Ducea and the uncle: three men, plus God, and then the federalist and the priest, representatives of the three. Jesus had as a representative the parish priest and Mussolini in turn, for example, those who finally took the bridegroom from the maid. And the uncle had an intermediate aunt who imposed on us as punishment “fifty times you have to write this or that”. But below, there is a serious denunciation of the Church in the book.

Denounce this religious fundamentalism...

Yes, because telling a child to adore his uncle who goes to hell because he is a Jew and that that girl has to put her legs in the blood to save him, that if he goes home with his bleeding legs he will send him to heaven, and if the uncle punishes his nephew because he has committed a nonsense… yes, it is ridiculous, but the complaint against the Church is immaculate. And now, in this second book, even clearer.

So can we say that what you have written is a way of bearing witness?

Yes, he wants to testify to a tragedy and denounce the Church.

So, for you it was more important to testify than to write a beautiful novel. The literary aspect was not so important.

Yes, it's true. However, in this aspect it was first appreciated, precisely by the literary part, by the originality of the book.

And when do you think that the book has been truly successful, when it was later reedited by the editorial Sellerio in 1990?

No, he first received a literary prize, called Viareggio, thanks to which many books were sold. And then years later, when the book was reedited, he told the editor: “Look, I may have to tell you that this is not just literature, but my childhood.” “Make an offer to your uncle.” And in the end, that offer was a real therapy, bringing their names to light. That is why I said that I have had a lot of time to do all this.

From the book based film, you said it's beautiful, but not very beautiful.

It's pretty. I simply have to say that it is a neorrealistic film, which was very difficult to do, because it is full of children, and that is why events are counted. In my book, however, the facts are reported in view of the young woman. And that's different. It is not the same to count from the point of view of a child or an adult director, from the point of view of the director and the writer, among the Neorrealists, the writer of Visconti and De Sica, is not the same. And he's made a factual movie, but OK. However, their thoughts, what they wanted, could penetrate more frequently.

But there's something else, perhaps more important. What's the way to get out of a hole like this and get to live happily after suffering so much? Where's the key?

The key, for example, is to try to understand what has happened and why it has happened. “Why did the uncle have to hide and escape?” “because he was Jewish.” “But what does that mean? Why did they kill the Jews? But that's not an answer. It does not answer the question “why should the Jews be killed?”. And here comes the explanation. “The Jews have to die because they killed Jesus.” “Ah, yes?” “Yes, he was killed by nailing on the cross.” “(To! The method they used was very Roman. The Jews were stoned to death.” But of course, the Jews killed Jesus. And this blames them for an indelible, unforgivable, so serious guilt. How will a man who has killed God be forgiven? For Jesus is not a Jew, but God!

[The Catholic Church has long spoken of the role in which anti-Semitism was applied: “Every Sunday the ‘perfidy of the Jews’ was mentioned in the Mass, etc.” Only when speaking of this, his front was crumbling. She confesses that her anger has not yet calmed down.]

But from a more general point of view, after experiencing these atrocities, how can we get out of such a hole?

First comes, of course, the desire for vengeance, the vengeance, the death of the one who killed it. It was impossible, because who had to go? Yes, we knew who the murderers were, because the next day the English arrived, and soon afterwards another American arrived, sent by Albert Einstein, with a letter. According to the order, Einstein's relatives had to die, but not us, the guests. The investigation of who the murderers had been was then completely banned. The path of revenge is therefore abandoned.

So later on, all this anger led me to discover the real culprit, and I consider the Catholic Church to be guilty. Here's my rage. Because, why doesn't the Church make -- self-criticism and doesn't say it was complicit and, even more, that it demonised this people?

So can we say that the book Zerua comes down and saved your life?

That book, and also the latter (Londinese Journal). Because I speak in this book as I've never done so far. The sky collapsed, it wasn't born for no reason. In this book, I tell you what happened before, how I was before I wrote: I didn't eat, I couldn't swallow anything, and how I went to the psychiatrist. The sky -- of course, it counts on childhood, and in that sense it's earlier. On this occasion, however, the situation prior to the drafting is mentioned, so it is earlier in this sense.

It's very interesting how the psychiatrist saved you from suicide. You know that you received it very hastily.

Yes, she wanted to get me what I really felt, and so she found a way to save me. When he saved me, he clearly told me what I had to do: write what I had seen, face memories. He asked me, “What do you want from me?” and I said to him, “Save from suicide.” She had no other way out, or she had saved her, or suicide.

And does your work and that of Primo Levi have parallel from the point of view of testimony?

I don't know, because I haven't read it. I didn't want to read because I was afraid. I know what it is and what it wrote. But she had written what I'd seen and I couldn't get to look at what I'd seen. I thought, “I could die and I don’t want to die.” But I thank you very much for writing that book. Maybe I read it now.

We have a final question for you about your work as a painter in recent years. We have already seen the Album di famiglia collection on the Internet, and we would like it to be exposed in Euskal Herria, if the cultural authorities in the area did so and accepted it. Would you like?

Among the Basques? Of course, yes! Instead of the eighty paintings you can take about 50. They are mild and we have to tell the insurers that they are not paintings, but comments to a book. And they don't have any value.

After the interview, we told him that the next day we were going to go to the cemetery of La Badiuzza, where his uncles and cousins are buried. He took a paper and made us a plane. We left home with him under his arm, with some chocolates that we really liked (“Mangiamo i cioccolatini!”) and a little wine he gave us. We've come together to have coffee the next day.

In the morning, he made his daily purchase at the Campo dei Fiori, the coffee shop road. Then, when we asked him if he wanted to accompany her at home, I said no, that he was going to look for the newspaper and that, to follow us, he would fix it. Ten minutes later, on a street billboard, we've seen him read the newspaper. We say hello again with a “till soon”. Next stop, Florence. About 20 kilometers from there, the cemetery of La Badiuzza.

Ekain honetan hamar urte bete ditu Pasazaite argitaletxeak. Nazioarteko literatura euskarara ekartzen espezializatu den proiektuak urteurren hori baliatu du ateak itxiko dituela iragartzeko.

Aste honetan aurkeztu da Joseph Brodskyk idatzitako Ur marka. Veneziari buruzko saiakera. Rikardo Arregi Diaz de Herediak itzuli eta Katakrak argitaletxeak publikatu du poeta errusiar atzerriratuari euskarara itzuli zaion lehen liburua.

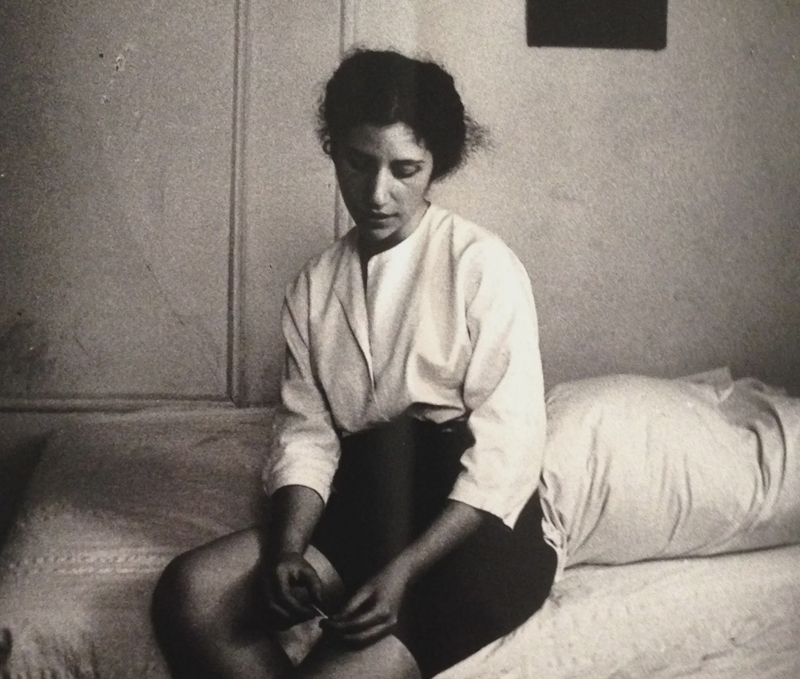

"There were women, there they were, I met them, but their families locked them in the mental hospital, put them in electroshock. In the 1950s, if you were a man, you could be a rebel, but if you were a woman, your family would lock you in. There were some cases, and I met them... [+]

Gauza garrantzitsua gertatu da astelehen honetan literatura euskaraz irakurtzea atsegin dutenentzat: W. G. Sebalden Austerlitz argitaratu du Igela argitaletxeak. Idoia Santamariak egindako itzulpenari esker, idazle alemaniarraren obrarik ezagunena nobedadeen artean aurkituko du... [+]

Asteazken honetan aurkeztuko dituzte Erein eta Igela argitaletxeek Literatura Unibertsala bildumako hiru lan berriak, tartean Maryse Condéren Bihotza negar eta irri (ene haurtzaroko istorio egiazkoak). Joxe Mari Berasategik euskaratua, idazle guadalupearraren obra... [+]

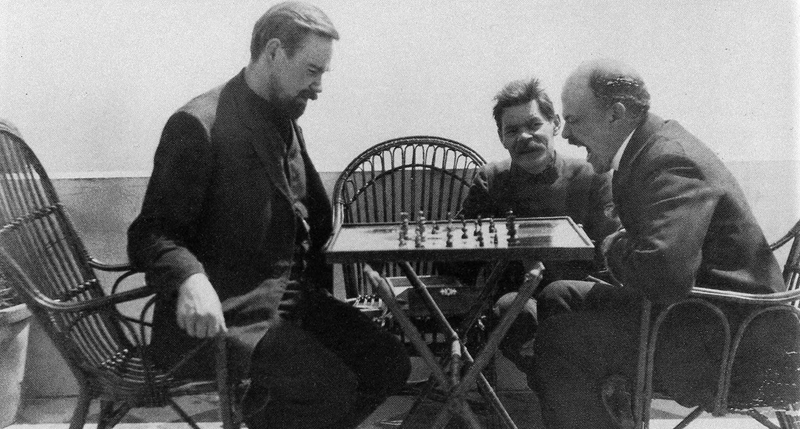

Wu Ming literatur kolektiboaren Proletkult (2018) “objektu narratibo” berriak sozialismoa eta zientzia fikzioa lotzen ditu, Sobiet Batasuneko zientzia fikzio klasikoaren aitzindari izan zen Izar gorria (1908) nobela eta haren egile Aleksandr Bogdanov boltxebikearen... [+]