This week many families will take a trip to the cemetery once a year. How many of them will leave the children at the home of a friend or relative with the best intention of protecting them from their relationship with death? You don't know, because there's no statistics about it, of course. They do not need them, for we can easily see that our society has concealed death, and especially that of children.

The Western adults of the 21st century live uncomfortable with death, until it becomes taboo, which is reflected in the education we give to children, both in families and in schools. Above all, the Navarra Idoia Sara highlighted the deficiencies that occur in this second area, in the work published last year at the School of Death Treatment (talking about death). Sara conducted the exam as a final career project to conduct pedagogy studies at the HUHEZI school.

A terrible event incites Idoia Sara to pay attention to death. On the verge of finishing her studies, her partner died suddenly. This made him see the inability of the educational system to manage these kinds of situations: the teachers of the center of his daughters contacted him to ask for advice, since they did not know how to act with the children.

Lack of training

The pedagogy of death in teaching is not taken into account either. Sara concludes that there is extensive literature on the subject, that professors consider it to be a field to work in school and that students are interested since childhood. So what makes the classroom so little talk about death and – often – so inopportune?

Teachers, like any other, are not prepared to talk about death, that's Sara's answer. From the interrogations to nine professors, he concluded that the subject is only discussed at school when death is approaching, and in these cases the lack of resources of educators and the insecurity caused by it are evidenced. Attention should be drawn to the attitude of some towards the consultation itself: “Someone told us he didn’t feel comfortable, and the two people didn’t give it in writing, but orally, because they were moving inside.” According to Sara, it is clear that talking about death is not normalized, not even for education professionals. “That’s why I think training is the way,” he says.

The teachers who answered Sara's questions also talked about the need for education. “Many have never received training, they only know the hand sheets that they share about grief in health centers.” A few had received the 12-hour course organized by the Faculty Support Center of Pamplona, based mainly on the process of mourning, but which only mentions in depth the pedagogy of death.

Trying to protect children, getting the opposite

“In the welfare society we keep hidden everything that can lead to death (sickness, old age…),” says Idoia Sara. The processes of death, in most cases, take place in hospitals, away from home and from the sight of children. Sara's study mentions, among other things, the idea that the Navarro psychologist Iosu Cabodevilla has given in the book Dolua in children: “Adults, wrongly, think that in order to protect children, because they are emotionally vulnerable, we must move them away from the suffering that can attract death.”

However, this desire for protection has an opposite effect. Sooner or later, the death of a close person is what will touch most boys and girls, and if we deny them the resources to face that moment, they will hardly be able to develop an appropriate strategy for the grieving situation.

Sara wants death to work normally in the classroom, to develop awareness of mortality since childhood. From the age of two to three, boys and girls know death, although their meaning is not fully understood, until they are at least 10 years old. Because they don't realize that you can't return from death, and less so in the case of the little ones, that they will also die.

The story, the right instrument to talk about death

Idoia Sara is clear that death has to be included in the resume, but she doesn't see how clear to do it. “Create didactic units? Spend fifteen days studying the subject to another? It's more than that. A certain sensitivity, a general view... Death has to be a cross-cutting issue, but it is not so easy to find a place in the stiffness of the resume.”

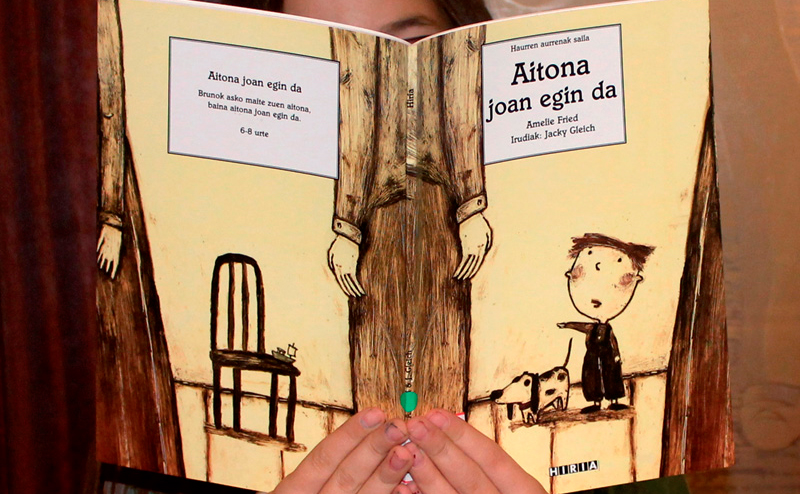

However, it makes a concrete proposal: use stories. “Through stories we can address emotionally complicated situations.” Stories allow the development of empathy, while slippery themes make it easier for the child to live from the distance.

The professor of the UPV/EHU Txabi Arnal analyzed in her doctoral dissertation the treatment of death in children's literature. In an interview with the Journal of Teaching & Learning Language & Literature, the Algerian writer and researcher stated that children's literature rarely mentions death. “There is no room for sadness. We live in the society of success and consider death a failure, so it is discarded.”

Arnal has detected lights and shadows in the works observed. It says that there are aspects of the issue that are being dealt with in a very appropriate way, but that in others there are significant shortcomings. “The usual characteristic of the works I have analyzed is that they show no more than the softest side of death. Incurable diseases, suicide, euthanasia... are virtually absent. The description of the body and the changes that occur in the body due to time or disease are uncomfortable to treat.”

The key, honesty

The youngest relate death to old age. Should we explain to young children that, as young people, one can die? We ask Idoia Sara. Here is the answer: “You have to explain things to them rather than cruelly, as you feel, but if you don’t ask, I don’t think you have to insist too much on it, because it gives them a lot of concern.”

Nevertheless, Sara believes that some things need to be made clear to the youngest. For example, we won't see the person who has just died, or we don't know where he is. Children often talk about the physical situation of the deceased (heaven, hell, graveyard…). “They’re used to listening ‘it’s in the sky’ and then they ask: ‘in heaven, but where? I look up to the sky and I see no one.’ It must be made clear to them what has happened to that person and that he is now in our memories. Beyond that, if it's in the sky, if it's become a star ... Boys and girls will build fantasy but are quick and know how to distinguish what is real and what is not.”

Diversity of beliefs helps

The beliefs of each family can influence the education of death. One of the teachers who answered Idoia Sara's questionnaire said: “Today we have students from different cultures in the classrooms. We will have to leave room for everyone and take advantage of that diversity. At least it helped me to die.”

It would be a reproach that a family intends to hinder the work of the teacher when the opinions that appear in the school do not coincide with the beliefs of that family. Or, simply, it may happen that parents are surprised and directed to the teacher, as the child has explained to them that that day they have talked about death in school. “If you do, you see the need right away. I have noticed a change of attitude, when something like this has touched me.” Instead, for the whole of society to change its attitude, more will have to be expected. Let's see if it's not eternity.