"Civil war is not a matter of the past"

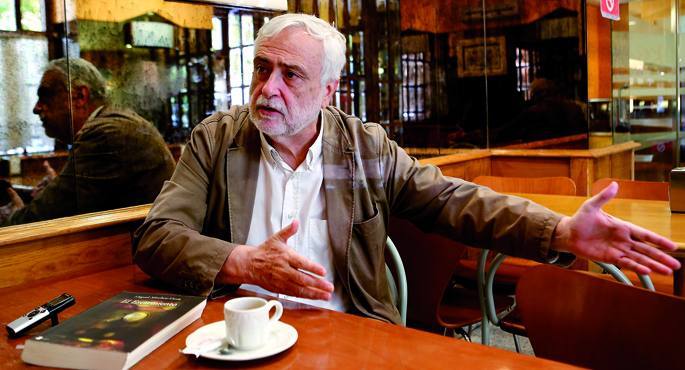

- In the book El Escarmiento (Pamiela), Miguel Sánchez-Ostiz (1950, Pamplona) explains the “experience” that Emilio Mola and company started from the summer of 1936. The Belarusian writer, who has already travelled a long way in the field of literature, has done a great historical job on this occasion. Using a beautiful prose, in addition to explaining how it emerged, developed and justified repression with the fascist uprising of 1936, he has described in depth the impact that all this has had on current society.

Talk again about that “fucking war.” Why does a writer with a long and fruitful literary trajectory enter the historical realm to complete this tremendous work?

On the one hand, because it was time and on the other, because he had been trying for many years to carry out historical work on war. After all, it is something we have lived here since we were young. It's always been present in our minds. I remember when we came from the people, when we went through Forgiveness, they said to us: “We are going to pray for our Father.” Why? He had poor drinking water because along with that manger they killed people from Pamplona. Same thing when we were going to Hondarribia. In the face of Lantz's painting there is another Father of ours to pray. Everybody knew it and a lot of other things. The one from Oricáin, the deepest caves of Urbasa… I found out about them when we were 11 years old, when we went to Bakaiku they told us everything.

But even though in Navarre these issues are widespread among families and on the street, until recently you have not addressed the issue.

I started writing about it in 1985, when I got a whole rich library on this issue of a landfill at Paseo de Sarasate. I started researching who I belonged to, and in the end I immersed myself in the subject. I started a lot of readings, everything that was then written: both the books that were obtained from that library -- most of them published outside -- and those of the writers that were always here, who joined the Francoists. Iribarren, Pascual, Foxa…

I started with the intention of writing a novel that would reflect the atmosphere of the Pamplona Falangists, and in that task I did a great newspaper work, with many notes and tokens. But, in my view, my conduct at the time was antipathy, and it seems to me that it can be very useful to justify the victors of war. Taking away the political traits, I was going to dedicate myself only to the literary or aesthetic part. And that's not a fraud, but at the same time it is. Foxa and some writers here, like García Serrano, wrote very well. That must be acknowledged. But they also didn't miss the opportunity to write huge brutalities, one after the other. They wrote well and the two best writers Navarre had were Falangists: Rafael García Serrano and Angel Pascual. Each with its style. The appearance of García Serrano is a tremendous one, but it gives a real nausea. At the same time, it offers us many keys to getting to know the Navarre society of then and today, sometimes through small details. For example, when he wrote: “We’ll break in Sanfermin, but then we’ll kill everyone.” Or when I realized the political confusion that was in the courtyards of Pamplona. When he described the atmosphere at the sports club Larraina, it was thought that politicians from different backgrounds gathered there, but then, due to the war, they aligned themselves at the opposite points. I've known it since I was young. In the old town of Pamplona there was a mixture of people, in poteo, in different associations, etc. Then, in some moments, it bursts. For example, when Montejurra happened.

I started writing the novel and left it. But in 2005, I resumed Molari's work with the stolen newspapers. That was also very advanced, but my editorial back then chose another book about Mola. My book was rejected and it felt good, because I was on the wrong track. In those years, I read everything I could. In the newspaper library, I did an impressive job, and I took advantage of what I did in the 1980s. Anyway, the last stimulus to immerse yourself in this issue was the visit to the fortress of Ezkaba a couple of years ago. There I was, among others, the daughters of Fortunato Agirre, the son of Thomas Dorronsor, the sister of Marvels Lamberto, of Larraga… I thought that “these people are worth it.” I felt that we were indebted to all of them, that I owed something to myself as well. The war did not have to be a bibliographical approximation or that could give rise to a business, because that is also happening.

His work reminds me of the writings on the war of Herbert Southworth. You have used different sources, contrasting newspapers, books, archive documents… You have used them to put the official history in place. What have you been and what valuation do you make of these tools?

On the one hand, I did a scrupulous reading of the newspapers here. If we read in detail the Diario de Navarra, in the news section brief, in the news of society, in the announcements… we will find the whole story of a city that remained in the rear. And that's what terrible events are about. Marino Huder, for example, was informed of the announcements of his inquiry during his imprisonment and after his shooting. Or the journey of Negrillos and Raimundo García Garcilaso to Badajoz, after a terrible Franco massacre, which was broadcast in the news of the Society.

As far as the bibliography is concerned, I have done it in one way or another, but not in much depth. There are things that don't exist. On August of 1936, I also lost a lot of documentation, after I started the work. Among the archives, the General Archive of Navarre has been a basic file, within which is the section of the War Commission. The Municipal Archive of Pamplona I have mainly used it for the acquisition of photographs. They have a very rich background, they have recently acquired another great collection of photographs about war, but we still have to see. I also looked at the records of the City Hall and explained some terrible things to me, such as contempt for the relatives of the victims.

I have based myself on them and I have come as far as I can. I haven't made a full book, I haven't wanted to step on the ground of historians. It's another book. It will not be a definitive book on this historical issue and I do not think “anyone behind me”, even if this is very Hispanic. I believe that there is still much to be written and with what is happening now, for example, with Falange’s complaint against that journalist, we are seeing that there is a great need to address this issue.

Civil war is not a matter of the past. So far we have not been able to write about this issue properly, neither against the General Cause, nor history or counter-history. The Garzón essay, or something like that, would have served to obtain a large number of documents, open all files by court order… but it has remained in nothing. The malicious and bad faith attitude that has been shown against all this gives me more arguments to work with history or counter-history.

Following the name of your blog, have you researched this topic with “enthusiasm”?

It has been exhausting. But I say again what I have said many times: that this subject or issue causes me or causes me tiredness, cannot be compared with the emotion experienced by those who lost my grandfather or my father through repression. I am unhappy about this, especially as the matter is very close. I'm not writing in Manhattan or in Madrid, in the literary society of the capital and something like El Jarama. No, I'm in Pamplona, living with my people, with my relatives, with my family, with my neighbors, with those who learned with me at school ... That is why I have sometimes written it with a lot of enthusiasm, sometimes with a lot of difficulty. I've had a hard time writing the book.

In any case, it seems that we have arrived late to pay that debt or to work on what has happened, right?

Yes, a lot. At the right time – after Franco’s death – no work was done as it should. The only one who addressed this issue was José María Jimeno Jurio, who was described as a jewel. In the same way, the people of the villages moved a lot to open the graves, recover the remains of the dead… but all that didn’t have much echo. Moreover, if the news was disseminated, the condemnation or despicable refrain soon came: “Those are separatist things.” In the 1980s, there were still a lot of people who could take the courts to testify. But that was not done and there is no cure.

Now we can do documentaries, chronicles or novels, but also very carefully. Recently, Vicenç Navarro, in a very good interview, said that the narrative of civil war is becoming too sweetened. According to novels or similar works that are being written, it seems that everyone killed him, that there were neither good nor bad. Republican legality is also relegated and it forgets that the civil war was absolutely planned, especially to provoke enormous repression over military activity.

Also in the realm of history do you perceive a similar attitude, a certain revisionism?

There's Pius Moa and company. I believe that at the University of Navarra they also continue to write about the civil war and from these chairs they are preparing and giving flesh to the doctrine of youth, which has recognition among their people, in their environment. Here we live in bubbles. Everyone lives in their trenches and we do not realize the importance of this revisionism or despise it.

What kind of follow-up will you give to the book? You mentioned that you are preparing El Botín.

Yes, the story will end in June 1937. For this, my support will be: the Francoist takeover of Bilbao, the death of Mola and the decree of unification of the Phalanx and carlism. These are the milestones I foresee for this work. It will not be the second part of the current book, but the continuation. I'll join the dialectic between today's and yesterday's, and I'll play with different areas. For example, how the events of the war lived from the everyday life of Pamplona, although quite far away, such as the bombings.

I'm not going to go beyond 1937, but perhaps, in another style, a non-historical writing, I can encourage myself to write in another book about some things that are happening from the current point of view. I already have the title, taken from a Carlist song: We will also die (We will also die).

Gogora Institutuak 1936ko Gerrako biktimen inguruan egindako txostenean "erreketeak, falangistak, Kondor Legioko hegazkinlari alemaniar naziak eta faxista italiarrak" ageri direla salatu du Intxorta 1937 elkarteak, eta izen horiek kentzeko eskatu du. Maria Jesus San Jose... [+]

Familiak eskatu bezala, aurten Angel oroitzeko ekitaldia lore-eskaintza txiki bat izan da, Martin Azpilikueta kalean oroitarazten duen plakaren ondoan. 21 urte geroago, Angel jada biktima-estatus ofizialarekin gogoratzen dute.

Bilbo Hari Gorria dinamikarekin ekarriko ditu gurera azken 150 urteetako Bilboko efemerideak Etxebarrieta Memoria Elkarteak. Iker Egiraun kideak xehetasunak eskaini dizkigu.

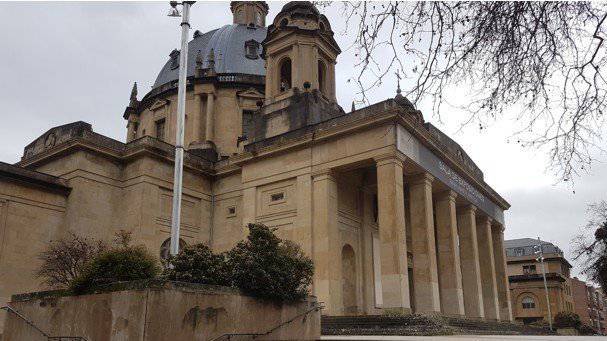

33/2013 Foru Legeari Xedapen gehigarri bat gehitu zaio datozen aldaketak gauzatu ahal izateko, eta horren bidez ahalbidetzen da “erregimen frankistaren garaipenaren gorespenezkoak gertatzen diren zati sinbolikoak erretiratzea eta kupularen barnealdeko margolanak... [+]

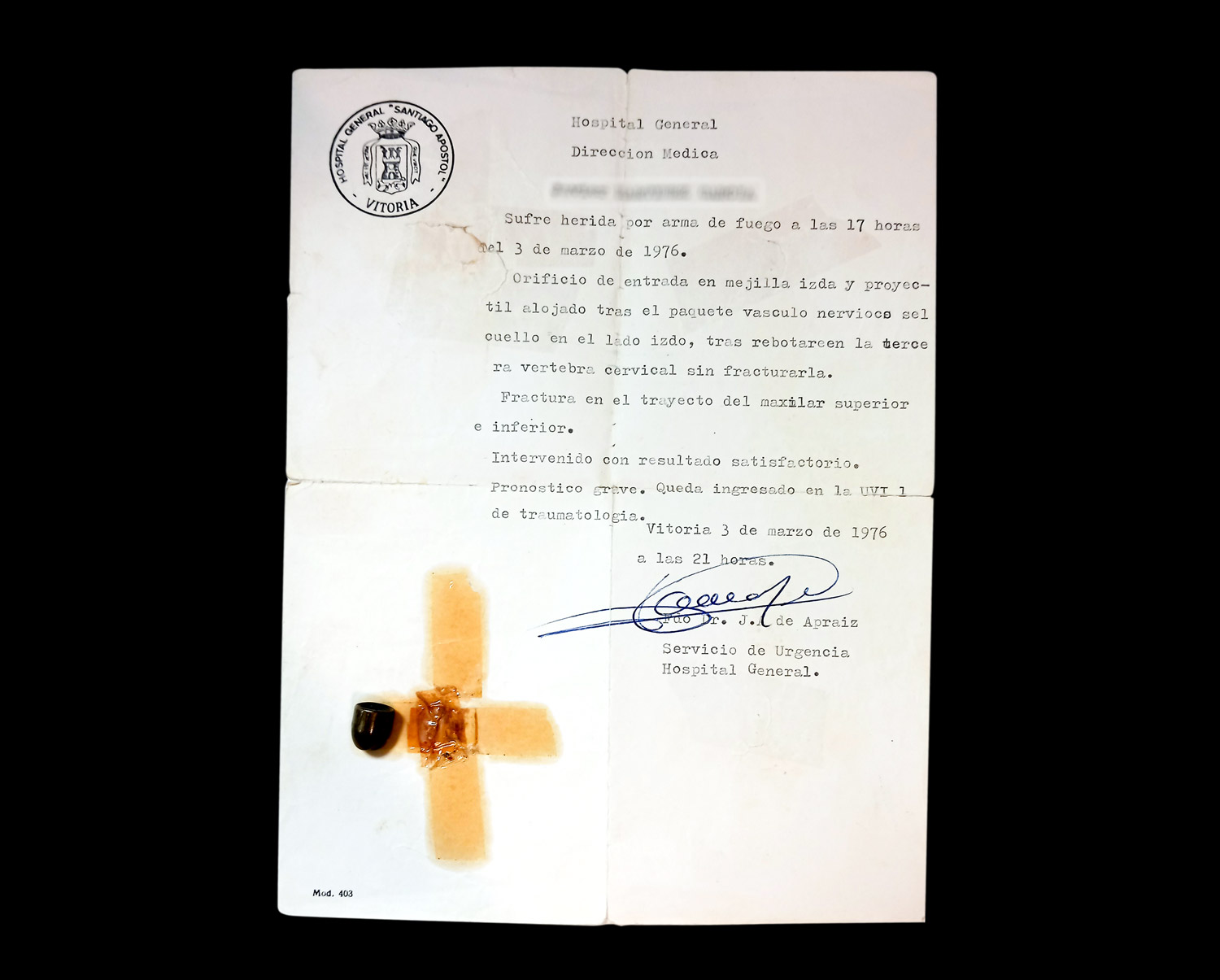

1976ko martxoaren 3an, Gasteizen, Poliziak ehunka tiro egin zituen asanbladan bildutako jendetzaren aurka, zabalduz eta erradikalizatuz zihoan greba mugimendua odoletan ito nahian. Bost langile hil zituzten, baina “egun hartan hildakoak gehiago ez izatea ia miraria... [+]

Memoria eta Bizikidetzako, Kanpo Ekintzako eta Euskarako Departamentuko Memoriaren Nafarroako Institutuak "Maistrak eta maisu errepresaliatuak Nafarroan (1936-1976)" hezkuntza-webgunea aurkeztu du.