Accelerator and mental body brake

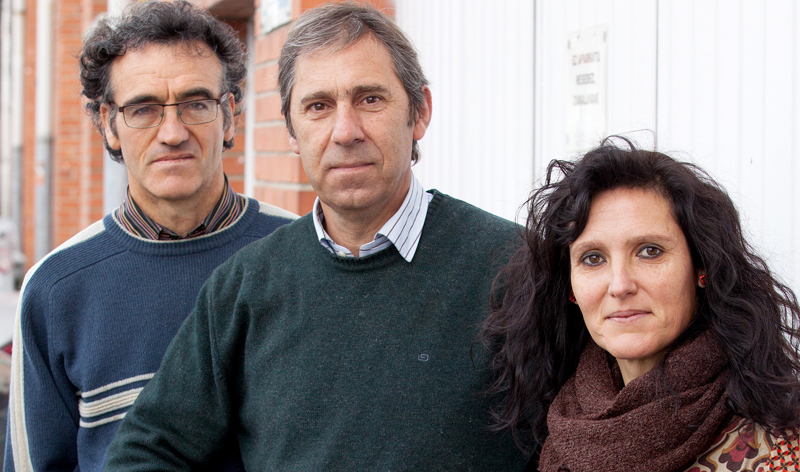

- The development of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) and the transport network, among other factors, have made society an increasingly sedentary society. Many people have found the alternative in sport. The practice of sport brings physical, psychological and social benefits. In addition to maintaining health, it helps reduce anxiety and depression that can lead to stress, increase self-confidence and develop social skills. Often, however, we do not take our limitations into account and set too great goals. What should hurt us then hurts us. We will get to know the two sides of the scale, focusing on what sports psychologists Gemma Sanginés and Aritz Olagoi have told us, and the Olympic triathlete Ainhoa Murua. Boundaries and goals are key terms in the psychology of sport. Stress, anxiety, pressure, fear, trust, motivation and the combination of other factors will determine performance, both in elite and amateur sport and in school sport. The needs of each will set the way.

Is it enough to want?

How many times have we heard the axiom Wanting is power in Spanish when we have evidenced our impotence and sought advice in our environment? But what seems like an absolute truth is the biggest lie for psychologists. “The idea of performance is one of the most aberrant and destructive,” says the member of the Platform for the Defense of Psychology, the Catalan Pep Font, on the new web of the association http://pdpd2012.blogspot.com. “This conviction pushes many people who doubt the motivation to go to our consultations because they want something but have not been able to do so. Coaching is common in this type of sentence. He wants to draw the public's attention, making him believe that we can get everything we want. They tell people what they want to hear with false misleading truths, with phrases like ‘the hard thing is to do, if you know how to do it’.

Asked about the subject, sports psychologist Aritz Olagoi (San Sebastian, 1978) has responded that a professional should never say that, “because it is not true”. In his words, “no matter how much you try and train, anybody will not achieve the goal they want.” It often tells us that goals collide with individuals' boundaries. “Behind that phrase is the vastness of human beings. It sells the dream of getting what we want, but men and women have limits. Psychologists, especially sports psychologists, should make athletes and their coaches understand that we also have limitations and that they may not be able to achieve the goals they are looking for.” For Pep Font and his colleagues, coaching, in short, is psychological counseling, “even though they behave as if they offered something new.” Coaching, however, is best sold, it's fashionable, and unlike the term psychology, people don't identify it with problems.

For her part, the psychologist Gemma Sanginés (Bilbao, 1970) told us that although the coachers do master masters and master some techniques, in order to perform a direct evaluation of a person, we have to learn “more” to “make no mistake in the intervention”. He works at the Gabinet Office from Suport to L’Esportista from the University of Valencia, which aims to help the athlete. In any case, he points out that psychologists should start using the term coaching, as they “train”. After all, sports psychology is above all psychological training rather than correcting dysfunctions. The rules, values and procedures of clinical intervention do not serve in this discipline, as people receiving aid in general do not suffer from imbalances. Only regular work is done on pathologies.

The objectives of Sports Psychology are to improve the performance and well-being of athletes and trainers, parents, teachers and other agents. “Sports psychology is not limited to high-level or elite sport, but also includes sports principles and leisure sport,” explains Olagoi. “Sports psychology is not magic,” he continued. “Psychological training, such as tactical training or technical training, takes time. There are no significant improvements in athletes overnight.” Psychologists participate with professionals from different disciplines (physicians, nutritionists and coaches), at least so they should, in the evaluation, intervention and follow-up processes of athletes.

The vicious circle of excess training

The tests of bicycles Quebrantabones and Treparriscos will be held this Sunday in the area of Sabiñanigo (Aragon, Spain), the half marathon Behobia-San Sebastián, the mountain race Ehun Milak, the duatlons and triathlons… More and more people practice sport not only to stay healthy, but also to overcome and compete a wide range of brands in the word. In debates about these kinds of challenges, the terms “madness”, “addiction” and “obsession” are commonly used in the face of the perplexity of people’s conduct.

“It’s true that there are people who prepare very much and can come to grieve,” says Olago. “They focus their lives on that, they measure the estimate for the outcome, and if things don’t go out as they expected…” As the triathlete Ainhoa Murua (Zarautz, 1978), who will participate in the London Olympic Games, has told us, “it is not about training much or little”. He says that if the butt trainer enjoys, for him that is better than “going from bar to bar or watching television at home.” The point is that there are people who give “too much importance” to amateur or popular races, and that not achieving the expected performance “makes them suffer”: “We all want to improve, but to have a bad time…”.

Sanginés says that “it can become ridiculous”, because amateur athletes live the competitions “surprisingly”: “It seems that when they reach the goal they will receive a prize of I don’t know how many euros”. However, in his view, there are “many myths” about this: “As beings we are, we are designed to move. We are becoming more and more sedentary, and that is why we are looking in sport for the way to break this sedentary lifestyle. That is a good thing. There may be a time when limits are exceeded and the pathology is given, but these are isolated cases”.

Asked if the appearance of the pathology can be detected, the Biscayan psychologist tells us about the overtraining syndrome. One of your symptoms may be trouble sleeping because the pressure is too high. “This usually happens in professionals or athletes who, without charging, train and compete like them. There may be a time when, even if you try, you won’t get the performance you would like – the result. When that time comes, you'll be looking for solutions and you decide to train more. A vicious circle covers you. You train harder, you dedicate more time and effort… and you can’t escape from there. If one day you can’t run out, you’ll notice the void, as if you’re missing something.” One of the consequences may be to think no more than that and to set aside important things (family, friends…) for maintaining “health”.

Speaking of the obsession with sport, Sanginés refers to endogenous substances that leave our body when doing physical exercise: endorphins.

Neurotransmitters of pleasure

Endorphins are hormones caused by our body. They act on the central nervous system and their main function is the inhibition of the fibers that transmit pain. Being an analgesic activity and generating a sense of well-being – reducing anxiety – they have been compared with opioids (especially morphine, heroin and codeine) that have biochemical similarities and hence their name (endorphin: endogenous morphine). They can be stimulating, because by releasing endorphins, athletes feel that they can contribute more, as if they had injected energy. Our body can release endorphins, among other things, in sex when it hurts us a lot, in eating some meals (such as chocolate) and in physical exercise. However, when talking about “addiction” to sport, a careful comparison must be made between endorphins and the drugs mentioned. It is clear that endorphins do not produce adverse effects such as drugs in the nervous system and are not comparable in quantity to exogenous drugs.

Aritz Olagoi tells us about another component: mimicry or the comparative process. “You may have seen that your neighbor made the Behobia-San Sebastian for the first time three or four years ago and gradually has been losing weight and making better and better brands. Start you too... In addition, the sports industry is expanding, both in terms of materials and physical trainers, psychologists or nutritionists. These services are very available and that can also influence.”

However, Olagoiti says that this comparison can generate pressure. “The athlete has to know how far he can go in defining his goals, where his limits are, depending on his figure, his training time, etc. We will always lose out when compared to others, and that generates pressure, frustration, because we cannot reach the limits we would like.” The Donostian psychologist tells us he's seen everything. “A person with a small injury who will answer you when you ask about expectations in order to improve their brand can come to the consultation. In that case, you should try to make you see that this is difficult to achieve and that you should perhaps rethink the objectives.” However, he believes that the psychologist should try to take the place of the athlete: “Maybe you’ve trained between four and five months, you’ve spent a lot of time on physical activity on leaving work and, unfortunately, you’ve been injured when the race day comes. Accepting that all the work done must be used not for the stated purpose, but for more humble purposes, is nothing easy. In a sense, it's also surprising, how is it possible that he doesn't see that he has to lower the target, but that's what happens. We can help you change your point of view, but the final decision is always in the hands of the athlete.”

Stress, inevitably

The last-minute injury is one of the surprises that the competition holds and leaves no one indifferent. “Competitions are stressful by definition,” explains psychologist Gemma Sanginés: “Total control is not in anyone’s hands. Self-esteem is measured by something you can't know. You don't know what's going to happen, and that's stressful. You’ve certainly tried hard, you’ve given yourself time, money… When you’re going to compete, the athlete will inevitably face stress.” It says that “all things that break balance” can be stressful: cold, heat… Stress, that point of activation, when it is well directed, can be positive, because it lives motivation and keeps the body awake, close to increased performance.

If, on the contrary, it generates anxiety, stress can cause problems. “What athletes have to learn and psychologists have to teach to avoid that anxiety, to take steps not to reach it,” says Sanginés: “That is, we will use the physiological part – activator – to improve performance and work cognitively to reduce the damage that stress can cause. By controlling the thoughts, we will influence the behavior of the body.”

The bilbaíno psychologist added that anxiety and injuries are related to anxiety and anxiety. “If you’re in a situation that creates a lot of anxiety and you’ve also pushed your body to the extreme, as happens in high-level sports, your muscles harden, tighten, you can lose your focus and make a movement too strong or bad. With physical materials the same thing happens: when excessive force or pressure is applied, it cannot be maintained and it will break.”

The perception of control. Mountain climbing

Last winter, the mountaineer Alex Txikon (Lemoa, 1981) stayed for three months at the Karakorum with the aim of climbing the Gasherbrum I (8,068 meters altitude). His expedition opened a path on the south wall of the mountain. In the summit attempt, however, three mountaineers who were part of the group died: Gerfried Goschl, Nisar Hussein and Cedric Halhen. Txikon decided not to go up with them and start the next day. “We had opened the way to the south wall, but we didn’t know under what conditions the plateau had to go through later, nor would the time stand,” he said in the Berria newspaper. “The forecasts were not the best and I had many doubts. My instinct told me not to go up and I heard him.”

We tell Sanginés what happened at Gasherbrum I. “Social pressure is a component to keep in mind,” he says. “You may be very clear that you don’t want to go to the top, but if the rest say yes… Why did the other mountaineers go up? Perhaps some of them would also have been afraid and it was as clear as Txikon that they didn’t have to rise, but because of social pressure… ‘Let it not be for me. If I don’t leave, it will be even more dangerous for them’… Such thoughts can influence decision-making.” Exactly what Txikon said about this pressure: “People told me that I could lose the train from the top, and that could put pressure on me. I have put a lot of money, enthusiasm, effort and time into the expeditions of last year and this year, but I made the right decision.” The bilbaíno psychologist believes that the three who died on the mountain were "likely" aware of what they were going to do. “But you have to put yourself on your skin. We're all different. Our brain is a machine for confirming hypotheses. Even if we collect objective data about time, if our hypothesis is that we get to the top, that will be the evidence, ‘we’ll adapt’, we’ll think.”

When we walk down the mountain there are factors beyond our control; to be as sure as possible, among other things, it is essential to collect information and have enough experience. “When I went to the Pyrenees with my friends in Bilbao, I was surprised to see that they knew nothing about meteorology: what they were announcing those clouds of one, how it was going to affect the other’s wind…”, Sanginés tells us. “To walk down the mountain you have to know the weather. If you have devices like GPS, better, but the illusion of control that these tools produce often acts against us, because we forget that there are factors that we can't control. If you go alone to the mountain, with the GPS on top, you fall down and you break your leg… the minimum emergency can be terrible.” With the experiences at summits, we have begun to talk about mechanisms for coping with fear and we have realised that it is a key word, not just in the case of alpinism. Fear generates two answers: paralysis and flight.

Fear, taboo word

“It’s curious,” begins Olagoi. “Athletes do not use the word ‘fear’, but it is something that is often behind their problems. And there's a fundamental fear: the fear of competition, and a lot. The most commonly used word is pressure. Sometimes athletes tell you: ‘In that game I had no pressure; as the rival was more skillful, I had less to lose and I did things better.’ I don’t know if they make them more orderly or if, because they don’t have pressure, they feel more comfortable and that they do better.”

“There is also physical fear,” Sanginés tells us. “By competing, two things are put at risk. On the one hand, the physical integrality, for example, that of cyclists going down very intensively. It is a common symptom among cyclists. Once, a Valencian triathlete who mainly practices the Mediterranean told me that I was afraid of the Zarautz Sea. On the other hand, athletes also fear the decrease in self-esteem. It’s hard to see that after an incredible investment, both in time and in money, the expected fruits are not picked up.” Triathlete Ainhoa Murua also believes that fear is an “important word”: “The fear of not getting what you expect is always there and in competing it is essential that you do not. In the bad streaks, when some disastrous results come in line, fear can increase and you have to fight it.” José Manuel Beiran, former basketball player and psychologist of Real Madrid, said that “we will never hear an athlete saying that he is afraid of competition; in men and women, fear is natural, but we do not accept it. Athletes put a mask psychologically to give the image of a hard and irreducible person.”

Failure, failure to achieve objectives, we are too afraid of it in our culture. In this sense, the mountaineer Alberto Iñurrategi (Aretxabaleta, 1968) has spoken several conferences under the title Porrotaren alde. The way to understand success and failure calls into question the adventurers who have a very fruitful trajectory. “Defeat after a real effort is a good failure. It contains many positive elements,” he said in an interview published by Galtzaundi magazine (PDF). “Lately I see in the mountain world that there are people who, with their trajectory in tremendous failure, use the top to hide that failure and sell it as a success. I've always said that what's really nice and interesting on the mountain, what really makes the emotion live, is the road. The summit is very interesting, a very nice complement, but the most important and indispensable is the road. When I say ‘for failure’, I want to value the thousand things that are learned by forcing oneself, that do not depend on stepping the top. You have to keep in mind the top, of course, it's pretty, but you can't give it priority. If in the mountain the goal is to reach the top in one way or another, there will surely be too many risks and ethical responsibility will also be discovered.”

We opened a little parentheses here. Professors at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, Tomás Montalbetti and Andrés Chamarro, state that mountaineers in general and climbers in particular value the risks properly, despite the fact that the risk perception is disappearing as the climber faces a wall of increasing difficulty. “As the climbers that circulate through the most complicated rocks, those that are more likely to fall or get injured, show a lower perception of risk, we understand that this can act as a factor that positively influences development,” the teachers say. “Making decisions on a voluntary basis reduces the risk perception.”

Idolatry of victory

For Iñurrategi “the mountain has been contaminated with the idolatry of victory”. He says that the “balance” must be sought in order to move forward without renouncing its principles: “Economic support is important, but we want to make expeditions in a concrete way, taking on the difficulties, posing challenges, tackling in the clearest possible way, limiting the chances of reaching the summit or the supposed success.” He added that there are many sponsors for mountaineers looking for victory, but there are also many who “value the way and bet on those values.”

According to the psychologist Gemma Sanginés, in schools, at home and in sports federations, work is done to transmit values to children and young people, but this effort is forgotten by the elite sport machinery: “Football matches broadcast on TV, car racing, etc. You can see how this motivational climate changes. Who preaches so much goes to the freak when Pepe [Real Madrid players] stepped on the hand of Messi [Barcelona]. The rules should be stricter, with more sanctions. Denouncing these facts is not enough. They're allowed by show, by money. The work of years is thrown away in the trash in an instant. It doesn't make sense. It’s a contradiction, a hypocrisy.”

As for the work done at the base, Aritz Olagoi spoke to us about school sport. He says that until the age of 13-14, taking into account the peculiarities of each age, the main objective should be education, “making it clear that it is not merely a hobby”. From that age on, perhaps we should look more at performance, “but without excluding, of course, the educating part.” He believes that competition is necessary and that “if it gets right” is positive because it helps to improve our minds as more will be required. In any case, the limits should not be exceeded. “Respect for the other is fundamental.” In short, sport is a powerful tool to educate human beings at any level, to promote their integral development. “That should be clear to coaches and educators on the one hand and fathers and mothers on the other.”

Under the shadow of the leader

“Many studies point out that one of the four or five main reasons for young people to stop doing sport is the trainer, because it demands too much or because it is inconsistent with what it says and does,” Olagoiti explains. Besides being a professional office, the Donostian psychologist is a member of the Basque Association Irun Iruten (Irun Iruten), specifically the Team of School Sports Coordinators. “I always tell the trainers that they have to understand the athletes, that they have to know what their desire is, how far they want to go… The trainer has to respect the athlete because there is nothing to do. The expectations of both must be adjusted to each other. Conflicts may arise, for example, when the athlete does not intend to go further, but the trainer, seeing his qualities, wants to squeeze more.”

Talking about the coach has given us the opportunity to also talk to Olagoi about the role of the leader. “In the case of the youngest, this figure is an educator, everyone understands that. Well, role sharing is from a young age: silent, participative, who likes to be above others... but not much work is done in that field. I think the image of the leader is mystified. In some cases, especially in team sports, some players use the figure of the leader to hide, to avoid assuming responsibilities. In general, in team sports, the player should assume many more responsibilities, because he often hides behind the coach or the leader.” As for the way of working, the Donostian psychologist tells us that collective and individual sports are “totally different”: “In

a group they can be between 10 and 20 people, each with their personality, expectations and goals. In these cases, I work with coaches, especially in relation to group cohesion. In the case of the individual, on the other hand, with the athletes, and in some cases without the trainer noticing. It's curious. The athlete does not want the coaches to know anything, because some relate the visit to the psychologist with the problems. In the case of the psychology of sport, the aim is more to improve performance. That’s right, athletes don’t usually come when they’re in their best condition, but when they feel stressed, when they can’t sleep on match eve…”.

“Have you won?” (Parents as a source of pressure)

Olagoiti believes that communication between parents and school (educators and coaches) should be better, because parents are also part of the whole structure: “We tell educators to communicate with parents often, to talk to them after leaving, and to explain if they have concerns. That closeness is important, because parents often stay out.” In general, he says that they are “happy” with the philosophy and values of school sport, with respect for others and with the priority of having a good time, as parents are sufficiently internalized. Another reality is reflected in the disturbing results of the study (PDF) carried out by the Cabinet of Sociological Prospection of the Basque Government in November last year: 25% of the 820 people interviewed said that “aggressiveness of parents” is one of the main causes of violent actions in school competitions (verbal and physical assaults between the public and athletes).

According to the Argentine sports psychologist Marcelo Roffé there is a fundamental question: “If after a game the parents ask their children, “Have you had a good time?” Hallelujah, we’re on the right track. On the contrary, if the first question is, "Have you won?", it's over, we don't have comfort. We don't want that model of fathers and mothers, who push and force, who become coaches of the child and their coach, who beat him when he does something wrong, who experiences victories and failures as if they were theirs, as if the honor of the family was at stake in the child's party. Parents can be motivating agents, but also pressure agents.”

“Especially in the case of younger people, conflicts can arise,” says Olagoiti. “The child has expectations that may be higher if he sees that he has his own qualities to progress in a sport. If parents turn these expectations into their goal, they can protect their child too much, increasing the pressure. The young woman may come to think that if she fails to achieve her goals she will end all the hopes of her parents. That fear may cause him to abandon his desires and try to satisfy only those of his parents.”

As age progresses, sedentary lifestyle increases among adolescents, more among girls than boys. Less and less, but there are still stereotypes in society about female athletes and also about fathers and mothers. There is only one reading of what Osasuna President Pachi Izco said in the Diario de Navarra (28-05-2012): “Women’s football is anti-aesthetic; other sports are much more appropriate for women.” Girls understand sport as something egalitarian at first, and it is often the adults around them who do it insignificante.Cuando the mother practices sport, the daughter will tend

more to it, and the same happens between the father and the son. However, the number of mothers who do some physical activity is lower than the number of fathers.

Intrinsic vs Extrinsic motivation

Among young people, one of the main reasons for stopping sports is the pressure exerted by the environment, closely linked to the results, and the stress it can generate. Getting connected with sport will be easier if emotional rather than utilitarian connotations – results – are sought, as fun and pleasure are the most important factors to keep the athlete motivated. Motivation is a psychological concept present in all behaviors of men and women. It is not perceptible and arises to the extent that real or artificial needs have to be met. It is a complex and changing process, conditioned by the combination of external and internal factors.

The Provincial Council of Bizkaia published years ago a report (PDF) on the reasons why children and young people practise sport and stop doing so. Reasons can be intrinsic (internal, personal) or extrinsic (caused by a factor in the environment). Enjoying, exercising, getting fit and health are intrinsic, while the desire to win, to imitate stars, to please parents and to succeed (social recognition) are, to name a few reasons. Striking the balance between the two motivation models is fundamental.

It is said that the intrinsic is oriented to the task or task and the extrinsic to the ego. The risk of extrinsic motivation is that when the young person disappears he will stop doing sport. On the other hand, if the intrinsic is imposed, once the objectives are achieved, the interest in action and the needs of self-realization will remain vital, as the comparative benchmark of the young will be himself. But above all, those who want to feed the ego feel more pressure and control to keep their self-esteem high. Trophies and prizes, threats, deadlines and pressure assessments reduce intrinsic motivation. In the case of women, especially in high-level sport, intrinsic motivation is imposed, as they move less, because economic prizes do not reach the same level as men. In the case of boys, intrinsic motivation is also very important, but it is often fed by external prizes.

We shall open a second parentheses here. Olagoi and Murua consider that there are no differences between men and women in the way they compete. “Gender doesn’t matter; there are very competitive girls, there are also guys who are not at all competitive,” Olagoi says. “At least in the Triathlon there is no difference, the prizes are the same,” added Murua. On the contrary, Sanginés has told us, based on his professional experience, that although he is aware that he may “be wrong”, men are more motivated by being better than others, and that women are looking above all for personal performance. “It’s not the same to say ‘I want to be first’ that ‘I want to improve my brand’,” explains the psychologist at the University of Valencia. She added that she receives more requests from girls to work social skills (e.g., to have good relationships with the group) than from boys.

The Sins of Elite Sport

Experts from different disciplines ensure that the psychosocial agents that have children and young people in their environment have to bear in mind that school sport and elite sport are very different. The competitive model is not adapted to the real interests and needs of children and young people. It can be physically dangerous (it can cause joint problems, muscle injuries...), psychological (anxiety, stress, frustration) and directly related to sports activity (starting in an inadequate modality). It is necessary, therefore, to make it clear that the main objective of teaching other values and reaching a high level is not to teach.

“It is necessary to see the warning signs that hinder the achievement of the desired objectives and to intervene as soon as possible,” we can read in the report of the Provincial Council of Bizkaia. These are the signs: cheating, lack of companionship, aggression, breaking norms, seeking above all success… If children do not correct or explain things to them, they will repeat the behavior of their idols: they will do theater, insult and learn inappropriate values. “You have to detect them and try to cut the root.”

Moreover, in order to maintain the level of motivation, boys and girls should be able to decide on the rules of the group, for example, to facilitate their implementation. For example: if a player comes late to train, he must collect all the material on behalf of the rest.

Similarly, the child's motivation may disappear if he or she is very afraid to lose. The pressure generated by a possible failure makes him see his opponent as an enemy and that permanent pressure can push him out of the sport. It is therefore necessary to teach respect to adversaries and to foster friendly relations with them. To teach someone to lose, you cannot constantly reward the winner. Other behaviors must be highlighted: cooperation, tolerance, effort... The anxiety for winning cannot dazzle us.

The ghost of doping, especially

Unfortunately, the reports, suspicions and falsehoods that are affected by fraud, cases of doping, different strata are often the ones that dot the sports news. Aritz Olagoiti considers that there are many factors that can encourage the athlete to use prohibited substances in sport. He explains that “objectives” have a lot to say: “In this competitive society, we set goals in comparison to the neighbor, and to achieve them we can be able to put health and values aside. Some are prepared to do everything necessary to meet expectations. How will the athlete make more money? How are you going to gain more prestige and recognition? Well, improving the results. To achieve goals far from their limits, you can be prepared to consume products that harm your health. All you're going to see is that goal, nothing more than that. Usually the side effects will appear long-term and the athlete usually looks short-term.”

For her part, psychologist Gemma Sanginés considers that some sports have doping as such: “In our society we are accustomed to these kinds of messages. This is seen in some ads that turn on and go to children and adults: the cousin of Zumosol, Nocilla, RedBull, I don't know what product to take strength... The message is there, one way or the other, we drink out there. There is, of course, a leap towards the use of banned substances. What factors drive you to take this step? It influences the social pressure exerted by the environment. ‘If everyone does, I will not be an exception’, some think.”

Ainhoa Murua also talks about the influence of her environment: “Perhaps, when you see that the people around you are getting ready, you also make that choice.” The Zarauztarra triathlete considers that it does not exist in her sport: “Those who cheat are everywhere, but I have not noticed anything at all. At first I was upset that people thought that all the athletes we were doping, but now that doesn't affect me anymore. It's useless to spin around everything people say. I am clear about that. If an athlete has improved a lot from one year to the next, I don't think anything weird. It may be because he's trained very hard, right?"

“Athletic anorexia”

External pressure can also lead to food imbalances. The prevailing beauty canons, the aesthetic ideals that set the image society, can lead the athlete to adopt harmful habits. Also the pressures exerted by coaches and peers. The psychological characteristics of the athlete should also be taken into account: perfectionism, compulsiveness, excess expectations (both those of the athlete and those around him), etc. That is why it is important that environmental agents (coaches, fathers, mothers...), together with doctors, psychologists and nutritionists should also intervene in prevention when the situation so requires. The risk of eating imbalances is higher when the weight itself is related to performance, either because resistance is sport (triathlon, cycling...) or because the categories are divided by weight (fighting, boxing...).

Maider Unda (Vitoria-Gasteiz, 1977), in line with “back with a medal” to the London Olympic Games “Weight is a rather complicated issue, because to be in 72 kilos when competing I have to have six pounds more throughout the year to be strong,” the magazine notes. He says they play with hydration and dehydration to have an appropriate weight when competing, “but you have to know, because people do a lot of barbarity.” For Ainhoa Murua, food is “very important.” “In the end, we are what we eat,” he says. “We have a great physical expense and to make it work properly it is essential to eat well. If not, it will be noticed in the performance. It is true that some athletes go through getting the weight they want. But that’s how long you’ll last.”

Some psychologists use the term “athletic anorexia” to refer to cases of abusive physical activity as a method of weight loss. In this sense, there is a risk for “aesthetic sports” (rhythmic gymnastics, ballet or artistic skating) and for those practiced in gym (aerobic, fitness or bodybuilding, for example). According to some authors (Zucker, Nomble, Williamson and Perri. 1999), the risk of developing food imbalances is higher in scoring sports than there are referees.

We ended the report with slightly alarming messages. So we'd like to go back to the initial idea. That is, if we know each other's limitations and put the goals in place accordingly, doing sport will bring us physical, social and psychological benefits.

-----------------------

On Jon Torner’s blog you will find more information on the psychosocial aspect of sport over the coming days, as well as an interview with Zarauztarra triathlete Ainhoa Murua on the London Olympic Games.

Realak azken partida galdu ostean –Malagaren aurkakoa– Whatsapp mezua jaso nuen, J.B. Toshack entrenatzaile ohiaren esaldi batekin: “Astelehenetan hamar jokalari aldatuko ditudala pentsatzen dut, astearteetan zazpi edo zortzi, ostegunetan lau, ostiraletan bi,... [+]

Guardia Zibilak 14 lagun atxilotu ditu Alacant, Valentzia, Valladolid eta Malagan, sendagaiak eta debekatutako hainbat substantzia sortu, faltsifikatu eta banatzen zituen talde kriminaleko kide direlakoan. Europan atzemandako produktu-kopururik handiena da DIANU operazioaren... [+]

Lekuko babestu batek [Urdaibaiko arraunlari ohi batek] deklaratu du ziztadak egunerokoak zirela: astegunetan, entrenamenduen ostean, eta asteburuan, lehiaketaren aurretik eta ostean ere.