Genetic information of individuals requires special protection

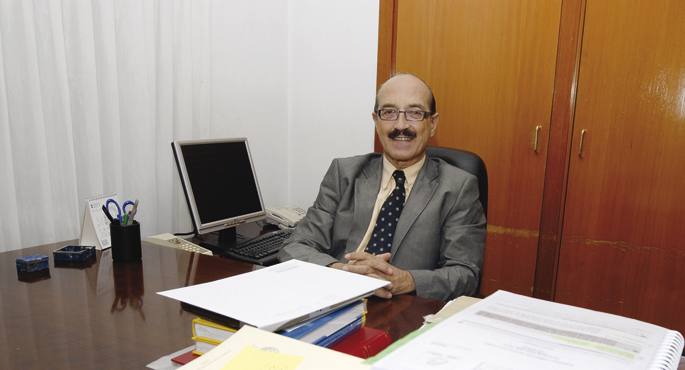

- Zaragoza (Spain) 1952. He is a professor of Criminal Law at the University of the Basque Country, where he has worked since 1996 at the University of the Basque Country. A year later, he was appointed director of the Human Genome and Law Chair established in 1993 by the UPV/EHU and the University of Deusto, a post he continues to hold since then. You spoke to us about the role that the right to progress in genetics and biotechnology in general should have.

The Chair of Law and the Human Genome was one of the best ideas of the 1990s. Wasn't it just good, was it necessary?

I think so. The development of biotechnology can influence the future of both humans and other living beings; attention to this development from a legal point of view has been a good idea.

Should the right place limits on research?

I would say that they are independent. We will have to see what problems arise and how to deal with them. It may be necessary in some cases to advise scientists of their responsibility. Some are absolutely responsible and others have no other objective than to move forward, often without knowing where they are going. When I say progress, I mean taking steps, but not necessarily improving. Society has a lot to say, and part of society is law. It should not be seen as a brake or a ban instrument.

Has there been any concrete evidence of the need to look at science from the law?

The Human Genome project promoted the creation of a tool such as the chair in the early 1990s. That was the turning point, but there was a precedent in the 1970s, when research on molecular biology gained strength. By then, molecular biologists had already warned how far their research could go and what consequences they could have for humanity. Two meetings were held in California, in which it was stated that the whole of society had to be involved, that they could not take some steps if society did not support them; and that the general criterion was to stop some lines of research until they were more aware of its possible consequences. That was not respected later.

To what extent can the chair affect? Can they introduce legislative changes?

For example, we participate in the Law of Biomedical Research. We made the first drafts to present them to the government. Then, the decisions are made by politicians, we are technical.

And do you influence research projects?

We participated. There is a project funded by the European Commission on biobanks. That is, a biological material of human origin for use in research. This project was coordinated by the Chair. Another example: At the European Council is the Steering Committee on Bioethics, of which I am a member, I represent the Government of Spain as a technician and chair a working group that analyzes the relationship between predictive genetic tests and insurance contracts. We intend to publish a Green Paper which will be a consultation document on predictive tests and private insurance contracts.

Is there no legislation on this?

There are countries that have it, but few. It analyzes the ability of genetic analysis to predict the future. Before, this capacity was very limited, but some of the current tests can say a lot about the future.

We are talking about the future health of the customer.

Of course, this is very important for an insurance company.

And in countries that have legislation on this, what does the law say?

There are no unified criteria. The European Council's Committee on Human Rights and Medicine said that a genetic test could not be performed if it was not research or patient care. However, the future use of such a test is not established. You have done a genetic test for health reasons and if the insurance company asks you for the result, what? There are countries that have no borders and others that think that these tests have to be controlled. Someone could try to take advantage of the situation, for example, if they know that in the future they will have a serious illness and make insurance very beneficial. But the truth is that the balance tends to get out of balance with big companies. There are a number of trends in legislation, from the ban on the use of such analyses to the authorisation of their use under certain conditions. For example, if someone wants to hire a prize for an amount, the insurance company will be able to ask for additional information, be it genetic testing or other tests.

Does the chair have a position on the protection of genetic information of individuals?

No. Everyone has their opinion.

And what's yours?

I think in general the idea of privacy is disappearing. You now, as you do this interview, are writing your notes, and you may have written “I’m bored with this guy.” If I read that, I wouldn't. But you can break that page and a gene can't break. I have millions of cells that tell me about my biological characteristics, although luckily they don't say everything. That information is not only about the present, but also about the future, which I probably don't know either. I believe that this information needs very important support. When it comes to using any private information, but especially if it is of this kind, it must be very clear what it is to be used for and it cannot be used for anything outside it. In any case, what is “for what”?

That is the key to the problem. What for?

This is one of the aspects regulated by the Law of Biomedical Research. If you use anonymous genetic information, nothing happens, you never know who that data is. In this case there should be no problem. But the researcher says that, because it is really justified, he needs more information about the person from where the sample comes from... There's the conflict.

In any case, almost nobody knows what your health will be like in the future, even if technology allows it.

It's getting closer. In the genetics department of Cruces Hospital [Barakaldo] you will see whole families every day.

Is it possible that one day genetic testing is mandatory at a given age?

It may be.

Is there anyone who asks for it?

There are a lot of trends and we don't know what the winner is going to be. It can be said “yes, if the objective is prevention”. Maybe it's not that bad. The key is that that information doesn't come out where it doesn't have to go. I am not very much in favour of using that information without further ado. But if you manage to respect privacy, that there will always be abuses, it can be good. If we were to get cancer to go away, who would be against it?

However, today we can know if a person has more or less chances of cancer according to their genetic map, but genetic engineering is far from being able to cure it.

And it's going to go a long way. We have been talking about this since the Human Genome project was launched more than twenty years ago, and no progress has been made. It's not about saying, "Here I have the puzzle of 23,000 genes, and I'm going to take one and put another in place." If you take away one gene and put another gene, you don't know how it can affect others. Epigenetics tells us that the information we receive is not just from parents, our biological experiences add information to our genes. Genes are not indifferent to external ones.

Henrietta Lacks izeneko andrea umetoki minbizi batek jota hil egin zen 1951an, baina bere gorputzetik eta bere baimenik eta jakintzarik gabe erauzitako zelulek oraindik, egundaino bizirik eta ugaltzen diraute, eta azken hamarkadetako biologia eta medikuntza ikerketetan... [+]