- The title phrase was chosen by the motto of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which began its work in 1995. This committee has subsequently been taken as a prime reference by the experts in pacification. This was not the only committee that was set up in the world, not even the first one, since there have been some thirty in some countries that have so far suffered a kind of systematic violation of human rights. The last in Brazil, where the Senate approved on October 29 the constitution of the Truth Commission to investigate the abuses committed during the dictatorship between 1964 and 1985. They have been given different functions and objectives: some have focused on the reconciliation of the confronted communities, others have put their forces in investigating and bringing to light what has happened in the past, and others have prioritized identifying and punishing those responsible for the violations. There is also a wide variety of achievements. At Larrun we will focus on the commissions that have existed in the world, emphasizing in some cases the reader and analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of each. Finally, we wanted to ask how and with what objectives we should set up a commission of this kind in the Basque Country. We interviewed Jon Mirena Landa, former Director of Human Rights of the Basque Government, and took advantage of the information from the book “Euskal Herriko Egia Batzordea” published by the association Lau Haizetara goan in 2009.

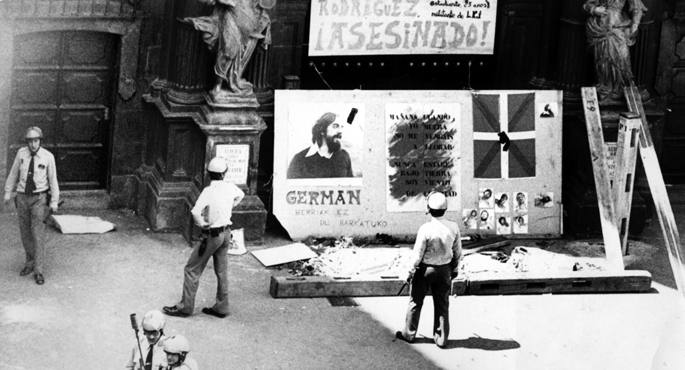

What's happened here?

First of all, it should be made clear that in Euskal Herria this is not the new claim of the Truth Commission. The Abertzale left again brought to the political agenda last February in the Kursaal of Donostia-San Sebastián the Haize Hegoa document for a resolution. In it, the party made self-criticism of its attitude towards the victims of ETA and assured that “the sensitivity shown towards the victims on one side has been lacking compared to those on the other side”.

The document presented called for the creation of a Commission on the Truth in the Basque Country as a step forward. This committee proposed that it should be independent and international in order to investigate what has happened in the past. “It should be politically impartial, with open participation and without exclusions.”

In the view of the Abertzale left, this committee should analyse the causes and consequences of the conflict, as well as the abuses that have taken place there. The PNV and the PSE-EE immediately responded that they do not see the need for such committees of inquiry.

The PNV stated that “society is very clear about what has happened in the Basque Country and does not see the need to set up a Truth Commission.” “We all know what ETA’s responsibility is for what it has had so far,” said Iñigo Urkullu. On behalf of the PSE-EE, lehendakari, Patxi López, and government spokeswoman Idoia Mendia responded to the Abertzale left. For the socialists there is no need for a truth commission, “because the truth has been there, because when ETA murdered people, when terrorism blackmailed businessmen, when victims painted and insulted themselves, the truth was there and it was enough not to close their eyes to see this.” Pp did not even make a point in the subsequent statements on this issue and said that it is not possible to move forward until the dissolution of ETA is requested.

In Euskal Herria we live new times, but it is essential to look back with seriousness and respect for the victims. The elaboration of an official list of all the victims of the last 50 years in Euskal Herria and the adoption of measures to prevent anything similar from happening again in the future is essential to promote reconciliation between the citizens of Euskal Herria, as has been seen in other countries. How many people have been killed by ETA? How many people have been killed by the Spanish and French States or their representatives? How many injured have ETA suffered? How many injured are the states? Some of these questions are documented thanks to the work carried out in recent years by various teams with the support of official agencies. According to data from the Spanish Ministry of the Interior, ETA has killed 829 people since 1968, although there is no total consensus on this issue. But who and how many are the deaths by the states? How many are the tortured and wounded? Since when will we start counting to establish a consensual narrative? The victims of abuses committed on behalf of the state following the 36th war, what do they say about all this?

There are many questions to be answered, and to treat them with seriousness and impartiality, the election of the Truth Commission cannot be avoided as quickly and as immediately with arguments such as “the truth has been there”. However, the heat of the political debate and the fact that the proposal was made by the Abertzale left could be the negative responses.

What are the Truth Commissions?

Experience has shown us that in the concealment of truth or in the non-application of effective measures of justice, there are open wounds in some sectors of society. In this way, the conflicts that some have considered to have been overcome are revived. International experience shows us that one of the most interesting instruments for this delicate retrospective work is the Truth Commissions.

A number of international organizations advocate the need for societies to adopt a critical attitude to overcome the painful episodes of history and to analyse the massive violations of human rights. Among many others, the United Nations High Commission on Human Rights or Amnesty International (AI) have an active attitude towards the establishment of the Truth Commissions in the world. In other words, the transition from a violent situation to peace requires three pillars: truth, justice and reparation.

These committees are, in the end, based on the exposition of the past, after having carried out in-depth studies. In some places, contributions have also been made for the opening of judicial investigations, which has enabled the path to justice to be opened. Finally, these committees make a set of recommendations addressed to the authorities on the recognition and reparation of victims, with the aim of helping to close injuries.

Between 1974 and 2012, at least 33 commissions have been set up in 29 countries. Over half in the last decade, and some are still underway, like in Ecuador, Canada or Brazil, for example. The results have also been very varied in all these years. There have been few people who have started the investigation and have disappeared from causes such as the Philippines or non-compliance with the objectives of the investigation such as Haiti. These committees have failed and are the last chapter of added suffering for the victims of the violations in those countries.

However, other countries have managed to reach the end. Different ways of working have shown that they have the possibility of influencing different areas. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa highlighted the massive dissemination of television and radio testimonies to over 2,000 public hearings throughout the country. This proved its value in restoring the dignity of the victims and in making the truth known. El Salvador identified those responsible for human rights violations during the 12-year civil war. Uganda was the first to be set up in Africa and had to be brought before it, together with former government representatives, accused of having committed savage acts in the country. Guatemala made public the massacres against the Mayan community. After the publication of the Chilean commission, numerous measures were taken in favour of the victims, and for the first time the Government requested forgiveness of the victims on behalf of the State. We will then have the opportunity to delve into them.

“All victims of genocide, all victims of crimes against humanity, wars, torture, extrajudicial trafficking and disappearances have the right to know the truth,” according to Amnesty International. This Non-Governmental Organization argues that knowledge of the truth about crimes is essential for victims to know what happened, where they are missing and for their suffering to be publicly acknowledged. Finally, according to IA, it is important at the social level to know the reasons that motivated these rights violations and to ensure that similar behaviors will not be repeated in the future.

They are a valuable investigative tool against state terrorism and other crimes that can be presented as a guarantee that there will be no historical revisionism in the future. However, the Truth Commissions have sometimes been criticized in some countries for not condemning crimes and for increasing the impunity of those who committed serious violations of human rights. The right to truth is, however, part of the reparation of the damage caused by the agents of the State, and such reparation should include, according to the experts in these matters, economic, social, medical and legal measures.

Bring the magnifying glass closer to several countries

As has been said, the Truth Commissions have not been the same everywhere in the world. In one place and another, human rights violations have taken different forms and, as a result, the committees that have been set up have also taken on different roles.

Next, we pick up a few strokes of the work done by these groups in different countries. Much of the information comes from Wikipedia and from the report From Pain to Truth and Reconciliation published by the United Nations Development Programme. For those who want to delve into the subject, this work of 56 pages is really recommendable and will find more cases than those mentioned here. The people who have worked on them look at the work of the committees in different countries.

The commissions that we are going to study below have been popularized by a successful search for the truth, or by the objective they have had in the search for reconciliation and reparation, by the methodology, by the constitution, by the degree of independence, by the incidence and also for ethical and legal reasons. Next, we will delve into the cases of Guatemala, Uganda, El Salvador, Chile and South Africa.

Guatemala, for the needs of the dialogue

In February 1999, the Guatemala Historical Enlightenment Commission (CEH) presented a final report based on the suffering of the victims. Christian Tomuschat was the chairman of this committee and, in his words, today the armed conflict seems to be something of the past. The armed confrontation ended ten years ago.

The Oslo Agreement, signed in Guatemala on 23 June 1994 by the Government of Guatemala and the National Revolutionary Union of Guatemala (URNG), led to the establishment of the CEH Commission. His work consisted of “clarifying impartially and objectively the violations of human rights and the acts of violence that caused the suffering”. Some of the members of the committee were international (UN representatives) and other premises.

According to Tomuschat, at first, the conflict had intensified between these two groups in 1960, but the Mayan population outside the conflict was increasingly confused. These two groups constantly pressured the Mayans because they wanted to get more people. In the end, they were trapped between the two opposition parties, without any support, before a state that thought that, in one way or another, the indigenous people were going to die. The war ended in 1996 and a total of 250,000 people were killed, most of them, as has already been said, being Mayan citizens, almost all poor peasants. There are still 45,000 missing persons and, according to the conclusions of the Truth Commission, paramilitaries caused about 80 per cent of the deaths.

Former Commission President Tomuschat said that the CEH put the victims’ conversations as a starting point and that it was not so difficult to gather testimonies. The victim states that they were met with the need to talk about everything they suffered in the last decades and centuries. It was the first opportunity to tell what happened to many victims.

Unlike the South African Commission, the South African Commission had no authority to grant amnesties, so they did not obtain any legal benefit from the recognition of what it had done. Tomuschat said that the perpetrators, the technical term used to designate the cause of the victims, did not show interest in going to the commission.

The group collected the testimonies of the victims and, despite the recommendations for reparation made to the Government, the Government hardly complied with them. The main violators of human rights were released.

Uganda, the former chairman to the commission

The Uganda Commission of Inquiry into Human Rights Violations, which worked in Uganda between 1986 and 1994, aims to investigate human rights violations committed in the previous 18 years. The last report uncovered the massacres committed for years. John Baptist Kawanga was a member of the committee, and explains that this was similar to what was created in Argentina. However, the former commissioner acknowledges that the commission of victims "did very little for the victims" in the attack. The main problem they faced was that human rights were violated throughout the various regimes and that many perpetrators became victims at the same time.

The actual victims were directly victims of human rights abuses and violations. It also focused on those who violated these rights and led those responsible to the Commission to tell their version of the story. In many cases, the victims met face to face with their torturers. In all cases, Kawanga says that the violence was promoted by the state, provoked by the government in turn against the civilian population. The commission also had the testimony of two former presidents and the security officers of the high-level posts. It was found that these had direct responsibilities in the infringements.

The Commission showed that violence against the civilian population began in 1962, when Uganda became independent of the United Kingdom. In the country there are three times of dictatorship between 1962 and 1986. Today, the country is made up of 28 million citizens from all over the world.

The three regimes carried out bloody repression of ethnic minorities and dissent. The Prime Minister after independence was Milton Obote, who in 1966 repealed the Constitution. In 1967, Idin Amine, his closest, took power with a coup d'état. Although in the beginning most of the population thanked for the change of power, today some researchers describe it as one of the cruellest dictators of the time. The Militia painted, displaced and murdered members of the communities of oholis and langis. But Obot seized power, and then the Kakwa and Lugbara communities also suffered cruel violence during the years in which he was murdered. The Last King of Scotland, based on the life of Idin Ami, helped Western citizens spread what happened in Uganda over these years.

The members of the Commission had to manage this situation and asked the public what kind of compensation they expected. John Baptist Kawanga says the situations were often very difficult. Both regimes had been overthrown and leaders lived comfortably abroad. How do we pay attention to the people who in these two times murdered their relatives? Who were they going to reconcile with?

The Commission was presided over by a judge of the Supreme Court of Justice and the investigation was of an absolute judicial nature. There, thousands of testimonies were heard in public, and almost all testimonies from high-profile members were cast through television. The media followed the work of the Commission in general in particular, and this expert states that the Ugandans marvelled when they saw that some people, once powerful, were called to explain their actions. For the first time in history, explanations had to be given. The Uganda Truth Commission highlights this difference between the things obtained: that the truth was first known.

But for many people there was nothing to do, they had deaths in the family. According to this expert, many of them hoped that the Commission would do more to help them and that the government would end up rescuing them. However, they still live with their tragedies today, among other reasons, because the government has no funds to do something like that, according to Kawanga.

El Salvador, from madness to hope

The United Nations Truth Commission emerged from the Peace Accords between the Government and the FMLN guerrillas in El Salvador and worked between 1992 and 1993. This committee emphasized its international character, the polarization that the country suffered, the fact that it had only eight months to carry out its work and the fact that the names of those responsible for human rights violations were brought to light. It is estimated that in the war of 12 years 75,000 citizens lost their lives on the island. Douglas Cassel was one of the editors of the latest report entitled Final Report and, according to him, one of the characteristics of this war was the excessive violence against civilians and the complete impunity of those responsible. There was no public hearing in this South American country because of the climate of fear and the real risk that was presented. For Cassel, despite the effort of the committee to put the recommendations into practice, progress has been made shortly afterwards.

It was composed of three members and had the collaboration of about 25 professionals: all international. According to the author of the report, when the members of the Commission moved to the country, the two communities were still completely polarized and mistrust between government supporters and supporters of the guerrillas was virtually insurmountable. There were few citizens who did not identify with one side or another. Fearing the consequences, important witnesses refused to speak.

According to Cassel, they faced many difficulties. On the one hand, 85 per cent of the direct victims are dead or missing, so there are hardly any direct testimonies from the direct victims. The testimonies were almost always given by the relatives around them. Initially they had a period of six months, so it was known that they could not receive 75,000 complaints, and eventually one in ten were received, although thanks to the work of other institutions, another 15,000 complaints were recorded and analysed. The majority of the victims were trade unionists, students, religious leaders, members of human rights groups, family members of victims, as well as farmers accused of defending the FMLN, among others. Finally, the work ended at the UN headquarters in New York, where its members received threats – Cassel does not say in his writing why – and left the country.

The commission made known the names of those responsible, including the country ' s senior military. The Commission recommended in its latest report the reform of the judicial system and the dismissal of all judges of the Supreme Court of Justice. In addition, he argued that it was not fair to keep some of the prisoners who committed “low-level” violations while the top perpetrators were on the street, so he also proposed a pardon for the incarcerated. There is also material and moral reparation for the victims. It also raised the possibility of declaring a day for the victims and developing a national monument with the name of all the victims, among many other measures.

In addition to the pardon and judicial reform of the imprisoned military, no invitation was received. The Government included the party that was still responsible for most of the previous violations, and Cassel believes that this greatly influenced the situation. Since the Commission is entirely international, at the end of the work the members left the country and no serious follow-up was done. Among the achievements, however, is the fact that the Final Report editor has retired within a few months of the senior positions of the armed forces and has written an authoritative and public version of the truth of history.

Chile, moral and historical mission

The National Commission for Truth and Reconciliation helped to make public in that country what remained after the human rights violations committed by the Pinochet military regime between 1973 and 1990.

When Pinochet left power in 1990, after 17 years of dictatorial rule, Patricio Aylwin took office and, on his own mandate, the Commission was set up. The commission consisted of eight people of different ideology, some of whom maintained an active attitude towards the regime and others who were in favour, but who would be criticized for the human rights violations committed by the authorities. They received the help of another 60 professionals and worked for nine months in the country. In February 1991, the commission informed the chairman of the 2,279 cases in which they were murdered, removed or tortured. Zalaquette, who was in the Commission, recalls that it was a time when the president made the report known to the country and deeply shocked Chile a few weeks later. Pinochet and other leaders of the armed forces publicly dismissed the report.

Zalaquette says they understood that the commission had "a moral and historical mission," as they had no powers to judge and punish anyone. However, the information they received about the violations was sent to the courts and eventually the names were made public by this means. According to the Commission, the families of the victims deserve special attention because of their situation in the Basque Country. The organizations that worked during the Dictatorship in collecting testimonies placed all the information in the hands of the committee. Thousands of people made their testimonies known in official locations. Zalaquette recalls that many people served to remove fear from these state offices and that the state’s attitude towards itself was an example of change. This committee could not oblige any individual to testify and therefore those responsible did not go there to give explanations. However, he points out that many victims served to begin to regain their dignity after having expelled their pain.

After the end of the report, there was a significant dissemination among the public. One of the authors of the report notes that he is satisfied because it was essential to establish a narrative that the entire nation would accept, which helped overcome the situation of denial and earlier division. Since then, a number of Governments have taken steps to prevent things from happening again in the drafting of the Gomedios, such as establishing a pension or scholarships for the relatives of the missing and deceased. In addition, the rapporteur states that many symbolic measures have been taken. The State asked the victims for official forgiveness and took their responsibility, with the name and surname of all the victims who built the “Murua of the Names”, opened the Museum of Memory and Human Rights and built the “Peace Park” in the largest place of torture, in Villa Grimaldi. The amnesty law was passed before Pinochet left power, and sentenced some 50 former military officers who did not save them, according to the same sources.

South Africa, public testimonies

The South African Peace and Reconciliation Commission was established in 1995, being the third commission in Africa and establishing that the objective was reconciliation. Among its novelties, it stands out that it promoted a great public participation both in the taking of office and in the election of its members, which earned it a great credibility among the citizens. Of the more than 300 candidates that came forward, the citizens elected 25 people, of whom President Nelson Mandela elected 17 to do this work. They formed the core of the group, but more than 300 people worked for the Committee. In addition, it was the first to open a number of offices and had a budget of over $1 million.

In English, TRC organized hundreds of public hearings: for victims, for those who committed rape and for public institutions. In addition, the Commission was given the necessary powers to investigate, request and order the arrests of alleged members of the board. In his last report he could cite his own names. TRC has also been the only Truth Commission that has had the competence to grant individual amnesties. Their crimes were offered to those who were willing to be informed in detail in the public hearings and to collaborate in the investigations, although most of those who had applied for them refused. Of the amnesty petition, 7,112 were issued 849, while 5,392 were rejected.

The committee heard the testimonies of over 22,000 victims, of whom 2,000 participated in public hearings throughout the country. They were open, and as a result they spread widely on television, radio and the press, reaching the entire population. On the website of TRC on the Internet, transcripts of public testimonies were put and on our site, anyone who wants to find a direct link to them. The President of the Commission was the Nobel Peace Prize Desmond Tutu. Each day, at the end of the session, the members of the group were in charge of checking that the testifiers came home safely.

The Commission, considered worldwide, worked in three subcommittees. On the one hand, the Commission on Human Rights Violations. The aim was to identify the victims and collect testimonies so they could witness their death. Secondly, the Amnesty Commission. His job was to individually investigate the amnesties and decide whether or not they are granted. The only condition was to recognize what had been done and provide information to help the research. Finally, the Committee on Reparation and Rehabilitation (or Rehabilitation). Its task was to make recommendations to the president to restore the human dignity of the victims.

The final report was issued to the President on 29 October 1998. However, those who fought apartheid did not see with good eyes that their crimes and systems were equated, and this issue had been at the heart of the national debate in the previous months. The Commission concluded by noting in its report that apartheid was a crime against humanity and that the armed struggle against it was a “just war”. However, he clarified that some of the actions taken against this fact were not legal, moral or admissible.

Although the Commission and the amnesty process tried to seek the contributions of white people, according to the latest report, “the white community was almost always against the Commission.” Apart from a few specific exceptions, the response of the previous government, its leaders, organizations and civil society bodies was to avoid, conceal or confuse what happened during this period.

The victims were asked what repairs they were expecting and recommendations were sent to the Government, both monetary and symbolic. However, former TRC Vice-President Alexander Boraine said the government was very late in giving those endorsements. Attorney Brian Currin has worked on the TRC team since its inception, and in the interview he gave to Argia two years ago he stated that in the democratic trajectory of the country TRC had a great value, especially on the issue of reconciliation. “It allowed South African whites to see what their government did and, by the way, understand why black people fought.”

A justice that has not been done in the Basque Country

In the last three decades, despite the fact that they have had different names and objectives, Truth Commissions have been set up in eleven countries that have wanted to close wounds from the past. In Euskal Herria there are also groups and people working in the defense of the Truth Commission. Jon Mirena Landa is one of them. This 44-year-old harbour port is a professor of Criminal Law at the UPV/EHU and former Director of Human Rights of the Basque Government. He has also been a member of the Argituz group since its inception. The fact that there is no in-depth debate in society is that there are no argued opinions of Basque citizens who oppose the network and the newspapers.

Landa was responsible for drawing up and presenting in the Basque Parliament a non-legislative proposal on the Commission on the Truth of the Basque Country at the end of the previous legislature. The proposal met with the memory groups of the Basque Country and worked together. However, the proposal was made before the change of government, at the last hour, and then the López Government has not taken any steps to deepen this path. We talked to Landa to find out how he raised the issue.

In their words, states normally commit and cover up crimes and, as they have power, it is difficult to do justice. That is why it considers the Commission to be an interesting way forward, because it is an extra-judicial mechanism designed to seek the truth. It needs a constructive and firm vision. “The main function of the Truth Commission is to do justice that has not been done,” he says.

How many people have died and been injured in Basque Country since the Spanish Civil War? How many for Franco's crackdown? How much in transition? How long after that? According to Landa, there is where to start. The professor of Criminal Law says that the violations committed by ETA, almost in their entirety, are investigated and condemned, but those committed by the State.

The book Euskal Herriko Egia Batzordea, edited by the association Lau Haizetara gogogoan, is also a reference work for those who want to look at the Basque vertex of this extensive subject. From there comes the following passage: "To date, there is still no official list of people who have been shot, disappeared, killed on the front, killed by famine and disease, no official list of prisoners, no exiles, no retaliation, no list of citizens confiscated. This reality has been investigated for years and has to be collected in civil and judicial registers. According to some historians, we are talking about over 7,500 shot and missing, 65,000 retaliation (prisoners, forced labour...) and 150,000 exiled and deported, 35,000 evacuated, hundreds of thousands displaced... Pure genocide.”

Jon Mirena Landa is convinced that anyone knows more or less how many people ETA has killed. They say there are over 800 common answers. “And how many people have died in the hands of the Spanish state since the transition? Many would say that maybe none of them have died. There's a big hole. They have worked hard to curb abuses, killings and violations of all kinds.” In recent years institutions such as the Basque Memory are trying to collect testimonies, document data and publish information about the state's repression. It concludes that some 10,000 people have been victims of torture in the last 50 years. Regarding the magnitude of the experience in Euskal Herria, they have pointed out that 2.5 out of every thousand inhabitants were arrested in Chile at the time of Pinochet.

In Landa’s opinion, “we have to push the commission because we need the truth.” In his view, if we have a minimum awareness of respect for human rights, Basque society should promote a Commission that prioritizes truth and recognition. “That’s where we can start.” We should also decide to what extent we want to arrive at justice, but the former Director of Human Rights of the Basque Government says that the minimum is for the responsibilities to be discharged. “Who has done what, name and surname of people. We need a solid foundation to move forward.”

It argues that the issue should be put on the agenda, and from that point on, that a working group should be set up to achieve the greatest possible consensus. In his view, it is best for the Commission to be made up of people who do not belong to any political party and who have the authority of the different political families. Despite being people who do not belong to any Basque Government, in his view, he should have all the support of the Basque Government. “You have to put people who respect society. Then you have to start deciding which violations you want to investigate, what times, until and a long time etc.” In his view, it is most appropriate to set up a working committee of between four and five years, since the subject is more consolidated, as other experiences have shown. “We have to look for something that satisfies us, that helps us advance democratically as a people and that, in addition to the approval of most groups, does justice to the victims.”

Mrs Landa considers that the Truth Commission is currently very workable. In his view, the most realistic way forward would be to draw up a law which would cover all the measures to be taken in it. “We can do this in the Basque Country and I would also call it the Truth Commission, because it has a lot of symbolic force, because to close wounds, symbols are needed collectively.” However, in his opinion, if the name is a source of controversy, it is better to start advancing with another name than to block it there. “Imagine that this commission opens windows to begin collecting testimonies from people who have suffered human rights violations in the Basque Country. That people are given a serious opportunity to go there and tell what they have suffered. If you collect that amount of information, investigate it and return it to society, do you realize the strength that the account will have?” he asks with enthusiasm.

In his opinion, “this and this, with all these facts, happened here in this historic period”, it should be the Truth Commission that sets out a way of saying it in the Basque Country, meeting the standards of Human Rights. The damage caused by ETA is well investigated, but understands that the crimes committed by the State itself are a covert reality. He argues that the political parties, seriously raising the issue around a table, should not be afraid of the truth, and beyond the political perspective, “all that is covered would be to bring to light”, and from there seek consensus regarding the steps to be taken.

Truth and justice cannot be negotiated

The victims of the unclarified violations, their relatives and friends, many of the human rights groups that we have mentioned earlier, and many Basque citizens are demanding knowledge of the truth and justice. Surely until this happens it will not be fully reconciled in the Basque Country.

Some representatives of the groups of human rights victims believe that truth and justice cannot be negotiated. They are inalienable rights. Those who committed these crimes must be punished. In addition, as a pre-reconciliation step, they consider the recognition of their dignity and the full reintegration of all rights into civil society to be indispensable.

“Until the problem of truth, justice and reparations, including guarantees of non-repetition, is addressed in all its complexity and depth, the Government of the Spanish State and the autonomous governments of Euskal Herria will continue to pursue the unjust track opened by the heirs of the Franco regime. This is a reality that they will not be able to hide, despite the many tributes and inaugurations that are being held under the presidency of the lehendakari at every moment. These acts will only be admissible when they are complementary to truth, justice and reparation; when they are used to separate these concepts, they become painful insults”.

The proposal put forward by Jon Mirena Landa states that the United Nations High Commission on Human Rights calls for three requirements to be met in order for this commission to be set up. First of all, it should have the political will to encourage and support the investigation of past violations. Secondly, armed conflicts, wars or repressive practices must be brought to an end. And thirdly, victims and witnesses should want such an investigation process to take place and show their willingness to cooperate with it.

“We should not be afraid of a mechanism of truth. If we are convinced that there is nothing to hide, let us set the conditions for this mechanism to do a good job. Putting trusted people and giving them the means and means to investigate. Let’s see what the result is.”

On an individual level, Landa believes that this is the debt we have to the victims, and above all to those who are still denied. “We are three million, will we not be able to satisfy these victims?” It sees nothing but advantages and is convinced that a serious approach by the Commission on the Truth of the Basque Country could achieve the support of the UN.

In many other countries, armed conflicts have had to end and it has been years before a sector has brought together the courage and strength to form the Truth Commission. Sometimes it has been the governments of the states, and sometimes the citizens themselves, organized in different ways. However, we will end up rescuing what Luis Pérez Aguirre wrote in the book El Uruguay Unpunished and the social memory in 1990, thinking with serenity that they could be written in the same Basque Country.

“We have been told that tapping our nose into these kinds of events of the past is reopening wounds of the past. But we wondered who and when he closed them. These are open and the only way to close them will be to achieve genuine national reconciliation, based on truth and justice. Reconciliation has these minimum and basic conditions."