"The view that is spreading is that linguistic diversity is not at all pragmatic"

- When he discovered the Translation and Interpreting career, the 35-year-old Zaldibartarra clearly saw his way: “To walk between languages, to play with languages, that was what I wanted.” She has been a communications lover, has been working as a freelance in the European Union since 2000.

In what areas is Basque used in the European Union?

It is used in the Committee of the Regions, in the committee where local authorities meet (mayors, Members…); and in some cases also in the Council of Ministers. Each State sends its representative to this Council and, in the case of Spain, as someone from all the communities is doing, when he adapts to the Basque Country he can speak in Basque, although with the current Government it hardly happens. We were surprised, for example, that the Mayor of Vitoria-Gasteiz, Javier Maroto, gave the conference in Euskera at the last plenary session of the Commission. In any case, they always ask for interpreter, since the protocol of use of the Basque Country was signed in 2005. At the beginning, José María Muñoa was the head of Foreign Action who spoke in Basque, speaks very well in Basque and it was very nice to work with him. Now they do not dominate the Basque so much, and what is fashionable is that they go to Spanish after saying “egun on” in Basque, intercaling some phrase in Basque, which for us is very confusing, or repeat what is said in Basque in Spanish and the listener listens twice the same. The Irish also do it: a word in Gaelic and a leap into English. The use of language in some cases is only symbolic, it is not an instrument of communication, and that is regrettable.

Another person and I interpret it from Basque to Spanish (and then interpret it from Spanish to other languages if necessary).

What place do minority languages have in the EU?

They are mainly used in official languages and Euskera does not have that status there, minority languages have very little space. The Council of the Regions also talks about Galician Basque, Catalan, but for example, Breton, Occitan and the minority languages of the French State cannot be used because it depends on the policy the country has. And in Parliament you cannot speak in minority languages, but I believe that you should allow it in Parliament, because in reality Parliament is the only democratic institution in the EU, the only one formed by elections. Politicians like Izaskun Bilbao are moving the issue, but, seeing how things are in the Madrid Senate, imagine yourself in the European Parliament.

In the end, on the subject of languages, and I am referring to official languages, not only to minorities, the view that is spreading is that diversity is nothing pragmatic, that assemblies are hindering a lot, that everyone knows English. Including the demands of minority languages is even more difficult, and to that must be added the context of the crisis.

Do you think there is little sensitivity to languages?

In the Netherlands, for example, English is the second language and they have no problem speaking English in the EU, no matter their language, but they do not have that sensitivity; if you can speak in a normal situation of your language, if it is normalized in your country, the language option is not a problem. It is different from ours when one language is imposed on the other. For example, when the cooperative languages of the State were approved in the Madrid Senate, many Spanish friends, despite being progressive, did not understand it: “It’s not necessary, we all know Spanish, if you know Spanish, why do you need to do it in another language?” they told me. It's related to feelings, and people don't understand what it means to be able to choose.

At the same time, it must be emphasised that the EU’s policy is to promote linguistic diversity and that Member States’ delegates can use their mother tongue, for example, it does not happen in other international organisations, as I know that there are no more than 23 official languages elsewhere.

Is it very different to go back and interpret?

It often confuses people, I am also a translator, but the translation is written and the interpretation is oral. There are several forms of interpretation: the simultaneous, the one we do in the booths, the one that works as a link, translating into some conversation two directions, and the consequential. We do not see much of what is said here, with what the speaker said he took the notes in the notebook and then gave the speech.

The hardest thing is simultaneous interpretation?

At least the most special. Listening, doing analytics, translating and pulling in another language, doing all of that all of a sudden requires a high degree of concentration, concentrating attention in two places and processing the information very quickly; it is true that a lot of people, being a translator, are not able to do it. We work half-hour shifts, as this has been shown to be the measure to be at a standstill and in good condition. We don't repeat words, we have to communicate ideas. For example, students of interpretation think that interpreting is translating all the words, and they don't realize that there are several ways to tell the same thing, which is the idea that needs to be transmitted, in the synthesis: What does the speaker mean by that?

You will have to know how to interpret what does not say...

There is always some purpose behind it, to sell something, to convince, to confuse the public with contradictory arguments… Our task is to analyse in advance what the context is – what topics will be discussed in the assembly, what attitude the participants have, the interests of each country…–. Many things are implicit and the work of prior documentation is very important.

It's a job that starts every day and that's the most special thing for me: every time, besides working the languages I use -- you have to keep them permanently -- you have to work on the issues, you don't know exactly what the speaker is going to say, and that gives you a point of adrenaline, accents, the way people talk -- these are variables you can't control, that point of nervousness is every day.

In the end, you will know a lot about the issues that are dealt with in the EU.

We know something about a lot of things, a little bit of everything. When meetings are very technical, we take courses or give us previous explanations, for example on the supbrime and other issues related to the economic crisis. Not only the terminology, you have to master the concepts, because the non-understanding of a word happens every day, but if you master the theme, the information will be completed.

Is the emotional aspect interpreted? How do you choose the right words to convey the tone, the expression…?

If it's very emotional, we try to express it, yes. When it comes to choosing words, we put ourselves in some way on the speaker's skin, since the interpreter is finally the speaker, we speak in the first person. In the end it is a question of balance, keeping the tone, conveying the message and transmitting the content as sincerely as possible. We use it to alienate the third person: if the speaker is wrong or insulted, formulas such as “the speaker says” can be used. Non-verbal language is also of great help, to catch irony, what you really want to express... There the problem is that the Finns, the Danes, and in general, are very rigid, perhaps they are saying something ridiculous, but they are serious.

So you put yourself in her skin. Have you never been tempted to say the words?

Ha, ha, ha. Sometimes yes, but it is not possible, it would be an opposition to our ethical and deontological code. It is not possible to remove, add or modify the information, although those who have for many years left their indications. There was, for example, an interpreter in Parliament who offered lottery votes. In principle, we are impartial, neutral, but at the same time the words I choose are not the ones you choose, because I am a woman and you are a man, because I have my vision of the world... The institutional discourse says that we are nothing but a channel, that collects and pulls information, until now it has been said that the interpreter is invisible, but we are people and we leave our imprint.

What kind of speeches do they tend to be?

It is difficult to find a good speaker, as well as here nearby, I believe that in general we do not have a politician who is a good speaker, we do not have an example. People know a lot about the issues, but talking -- It's hard to give a talk in public, developing ideas in a structured, accurate way. Sometimes, if the speech is too bad, we dress it up. There is a debate: if the original speech is bad, do you have to decorate it or convey the feeling that the speech has left? At the end of the day, it looks a little bit, at least in an intelligible way.

What does cabin work look like?

There are two or three people in each cabin and the aim is to control as many languages as possible among us. I would like to stress that this is a teamwork, because if for half an hour a word or data has escaped me and the rest of it accompanies me, we can press the mute button to silence the microphone and talk to each other. It has happened to several interpreters, talking with the feeling of having stepped on a mute… and having the microphones open.

The most ridiculous things usually happen with second sense word and sentence games, there is always an opportunity to confuse them. Interpreting humor is hard. The Dutch have a habit of translating their jokes directly from Dutch to English, word by word, and they make no sense. You see that only they laugh and you have to say, “the speaker has told a joke…” or something, and if you can create a humorous equivalent. And we have to keep up with the results of football and rugby, because they're always interspersing "your country has lost against mine," and jokes like this.

To what extent can one learn a language other than that of the mother?

You can learn, but not at the level of your mother tongue. Thanks to the Internet today we have all the languages at our disposal, but a language is really learned by speaking with those here, because they will provide you with the internal knowledge of the language, the nuances, the good modes of expression… Our work requires entering the logic and the thought of the language, because the language has a worldview behind it and to internalize it you have to know it firsthand. That is why our work is quite nomadic, you have to visit as many countries as languages studied, that requires investment… It is difficult to master each one’s language, to master all the records, therefore… That is why there are so few interpreters, even if he has lost the elitist tone he had before – interpreters, children of war, very cosmopolitan people….

What is the most difficult language to interpret?

From what I know, English. The language is very compact, with few words and many meanings, and it varies a lot. Anglo-Saxon thinking gets harder for me, it doesn't follow the Latinos' scheme and I don't have references.

I have experienced two very different linguistic experiences in two southern peoples in recent weeks. One at a conference organized by a public institution of a Basque people and another at a school assembly. If we were at the conference more than 80 people, I would say that 90%... [+]

Ekain honetan hamar urte bete ditu Pasazaite argitaletxeak. Nazioarteko literatura euskarara ekartzen espezializatu den proiektuak urteurren hori baliatu du ateak itxiko dituela iragartzeko.

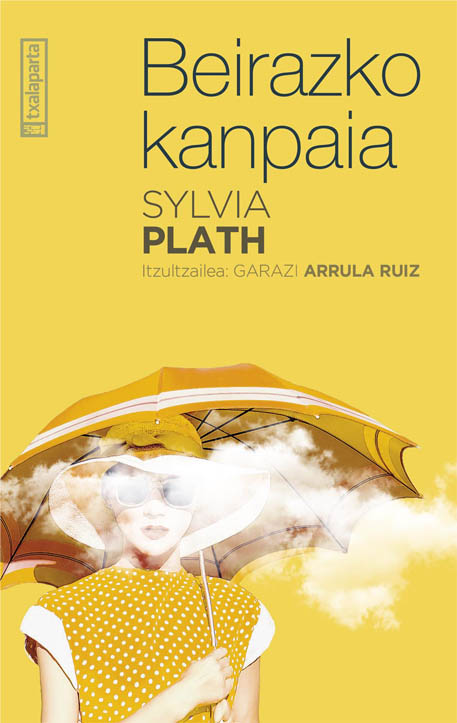

Many publishers rejected the book "The Glass Bell," because they understood it to be a barn and a bit light. It was first published in 1963 with the nickname Victoria Lucas. The glass bell could be a novel, but since it is a story very close to the author's life we could say that... [+]

Barrenetik zulatzen zaitut: 8 ahots itsasertzetik poesia antologia elebiduna argitaratu berri du Liberoamerika argitaletxeak. Ekuador, Mexiko eta Argentinako lau poeta eta Euskal Herriko lau itzultzaile elkartu dituzte. Martxoaren 30ean aurkeztuko dute jendaurrean.