“The Carthusian of Parma”, a great Masonic novel

- When Fabrizio, the protagonist of the Parma cartoon, recommends Farnesio to get off the imprisoned tower, he falls on an acacia. Why does Stendhal choose this tree? No French researcher of the writer asked himself this question – and it is one of the most studied in the universal literature – although the answer seems obvious. Until a German asks the question.

The Palme d’Or in Cannes, for example, is an acacia branch. The festival was launched in 1939 by Mason Jean Zay, minister of the Popular Front, to face the increasingly fascist and pro-Nazi Venice festival, although the first edition, scheduled for September, was cancelled due to the outbreak of the war.

The German who fell on acacia is Dieter Diefenbach. In 1991 he published his first research on Masonic remains (to Stendhal und die Freimaureri) and this research has given way to a second, more in-depth, text that has become the first French text on the subject, Les mystères de La Chartreuse de Parme, by Pierre Alain Bergher and published by the prestigious publisher Gallimard, in the collection L’Infini, directed by Philippe Soller.

Acacia is not the only Masonic imprint of the novel. The tower of Farnesio itself is invented in accordance with Masonic symbolism. It is shaped like a Pentagon, and five star-shaped angles –five points– make up the most famous Freemason star, which is displayed in the independence flags promoted by members of the secret society, from the Latin American to the Catalan stelada. The gate is surprisingly low and narrow for such an important building as the gate of the temple of the Masons, for the profane to enter in contrite manner, in order to understand the difficulty of passing from the profane world to the most initiated. One of the chapels is made of black marble and is decorated with the heads of the dead in white marble, as in the loggia of the master. In addition, during the construction of the tower, by order of the prince, all the participants had to act in silence, a seemingly absurd and useless detail in the story, unless we think of the law of silence that is imposed on the Masons.

The interior evokes the characteristics of the Masonic Temple: numerous chambers, some open, others secret, like the chamber of the master, which is forbidden to the profane. In one of the chambers he places an absurd cottage, unless we think that the lodge was originally a wooden cottage, an initial space in which Fabrizio will spend nine months.

Imprisoned in the tower, Frabric endures an initiatic ritual similar to that of the Masons. He also wisely tells us: “It seemed to me that I was following a ceremony (...) in front of my friends”, and it is the ceremony before the friends that takes place in the lodge.

For Diefenbach and Bergher, the protagonist of the Carthusian Parma follows a ritual of initiation similar to the Framazones. The chapter of the escape leads us to think that it has risen to the level of the masters. Chapter IX – where the priest Blanes receives Frabrice in the bell tower of the church of Grianta – belongs to the apprentice. And Comrade Fabrizio is explained in Chapter XII, Bologna. Fabrizio finds in the church of St. Petronius, in Bologna, “a triangle of iron placed vertically, with corners erect and many thorns to support small candles”. It is a reference to the Luminous Delta, one of the main symbols of the secret society. Only seven candles were lit. The number seven – the Seven Gates of Barcelona, the seven points that crown the Statue of Liberty – is the most important figure of the Freemasons. Fabrizio took the note in his head “later, with the intention of thinking more calmly.” They are

also the traces that lead to the Masonic biography of the writer. Fabrizio entered the tower on August 3, at the age of 23, and at that age Stendhal was initiated at the Sainte-Caroline Lodge in Paris on August 3, 1806. He is 23 years old when Julien Sorel dies in red and black. His French friend tells us that Diefenbach has discovered numerous numerical combinations that allow Stendhal to enter his initiation date semi-secretly, August 3.

Bergher discovers that Stendhal structures some of his chapters, such as the Mark Twain framazons in his book The Adventures of Huckelberry Finn, following the 22 symbolic figures of the main tarot arcanes. The French Freemasonry of the time of Stendhal studied astrology and Stendhal made him an astrologer the spiritual father of Fabrizio, the priest Blanes.

The writer’s artistic name is also thought of in the Masonic key, says Diefenbach. The author chose Stendhal because the origin of the German city is Steindal and the word “stein” – stone – is of Masonic symbology. The writer added the letter hatxe for its numerical value.

Stendhal dedicates the novel “to the happy few”, as he did with the first volume of Red and Black, as well as the history of Italian painting. Scholars have limited themselves to saying that the expression “happy few” – the few who are happy – was also used by Shakespeare (Henry V), as well as by Oliver Goldsmith – another Freemason, to say everything – (vicar of Wakefield). Now, Bergher and Diefenbach remind us that this is what the English Masons call themselves. This is how they are identified by a Masonic brotherhood hymn, Ye Happy Few.

It is very logical that Stendhal had been in contact with the English Masons during his stays in London. At least he must have had a deep understanding of them. Her magazine in England, London Magazine, for example, includes articles on Freemasonry and Rose Crosses.

Bergher and Diefenbach believe that Stendhal dedicated the novel to his brother Freemasons. Now, Stendhal could have taken the expression to speak of sentient souls in general, as he once said to a friend in a letter, knowing, of course, that among these sentient souls are, first of all, Masons like him.

For all that he has seen, Bergher – after Diefenbach’s initiation – concludes: If Mozart made the great Masonic Opera the Magic Flute, why wouldn’t Stendhal, his great admirer, think of making the great Masonic novel?

Irailaren 9ra gibelatu dute Kanboko kontseiluan gertatu kalapiten harira, hiru auzipetuen epaiketa. 2024eko apirilean Kanboko kontseilu denboran Marienia ez hunki kolektiboko kideek burutu zuten ekintzan, Christian Devèze auzapeza erori zen bultzada batean. Hautetsien... [+]

Oinarrizko maia komunitateko U Yich Lu’um [Lurraren fruitu] organizazioko kide da, eta hizkuntza biziberritzea helburu duen Yúnyum erakundekoa. Bestalde, antropologoa da, hezkuntza prozesuen bideratzaile, eta emakumearen eskubideen aldeko aktibista eta militante... [+]

The argument of a syllogism has three propositions, the last of which is necessarily deduced from the other two. It is with this deductive logic that I can analyze, for me, the long and traumatic socioecological conflict in Carpinteria that is taking place in Navarre.

The... [+]

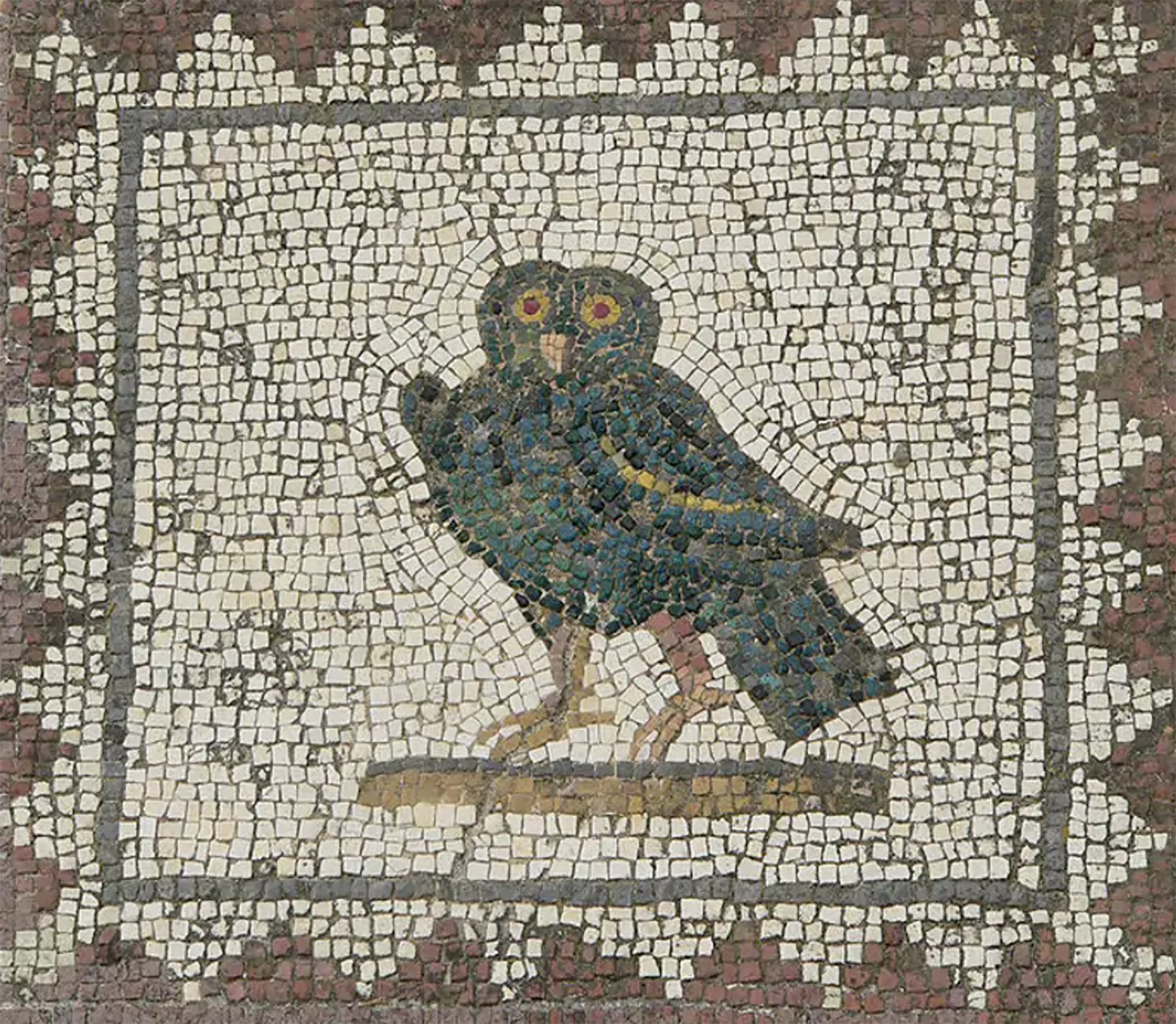

Poloniar ikerlari talde batek Sevillako Italica aztarnategiko Txorien Etxea aztertu du, eta eraikinaren zoruko mosaikoak erromatar garaiko hegazti-bilduma xeheena dela ondorioztatu du.

Txorien etxean 33 hegazti daude mosaikoetan xehetasun handiz irudikatuta. Beste... [+]

I have recently worked in class on Etxahun Barkox’s beautiful and touching cobla. The bad guy! The afflictions of the house began because of the creation of the “praube with beauty”, but in seventeen years she had entered the sea of misfortune, having to abandon the girl... [+]

We have renewed the dialogue in the secretariat of the faculty, for the most auspicious: they are far away, for their enrollment, the times when only the students came. The trend has changed for a long time, and parents – most notably mothers – are taking an increasingly... [+]

Gure lurraldeetan eta bizitzetan sortzen diren behar, desio eta ekimenen inguruan gero eta gehiago entzuten dugu harreman eta proiektu publiko-komunitarioak landu beharraz, eta pozgarria da benetan, merkaturik gabeko gizarte antolaketarako ezinbesteko eredua baita. Baina... [+]

_2.jpg)