Society

Environment

Politics

Economy

Culture

Basque language

Feminism

Education

International

Opinion

saturday 05 april 2025

Automatically translated from Basque, translation may contain errors. More information here.

The Muses

Dani Blanco

It happened at a party in Buenos Aires. A woman seduced a man who, being a pilot, addressed her as follows: “Fly with me. You can’t see the sunset I’m going to show you anywhere else.” The woman first refused, but the man grabbed her by the hands and loved her, and in the end she had to accept the proposal. If so, the woman boarded the plane dead of fear, leaving her life in the hands of the pilot. But when they had gone up into heaven, the man laid this hand on the woman's knees, and offered her cheek, and said: “Do you want to kiss me?” The woman began to apologize: “Kissing... is only kissed to the one who loves and always after getting to know him well. I just recently became a widow.” The pilot, however, did not despair, and gagged his lips to retain his smile: “If you don’t kiss me, let’s go to the water,” and directed the end of the plane to the sea.

It happened in the sky of Buenos Aires on a plane. The pilot shut down the engines to get the bidder's kiss. And the woman, frightened, discouraged, cried out horribly. As they crumbled towards the Río de la Plata, the man told her that he understood that he did not want to kiss her, because she was ugly, and again he managed to impress the woman's heart. “I love you because you’re a little girl and you’re scared,” she said, and with that the woman kissed him. “These are little hands! A little girl's hands at all! Give it to me forever!” he began to retract as he turned the engines on. “I don’t want to be a fool!” the woman replied. “You are so funny! I'm asking you to marry me. I love your hands. I want it to be just for me,” the man ventured, and the woman shamelessly pretended that they knew each other for only a few hours. “See, see how you marry me,” concluded the pilot, and also achieved it in the finish.This real anecdote between

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and Consuelo Uncin has reminded me of two films that I have seen recently by chance, namely Bright star by Jane Campion –remember the movie Piano– and The Last Stop by Michael Hoffman. The first one includes the last days of the writer Leon Tolstoy and reflects his fluctuating relations with his rich wife Sofia –Helen Mirren–; the second one also summarized the last months of the poet John Keats and, okay, maybe his couturier Fanny –Abble Cornish– has more prominence than the poet himself. Both films are beautiful, perhaps the first more social and the second more poetic, but the tempus and, in essence, the narration of both are similar, and I find that, in this tension between the writer and the muse, the winner is the first in the unconscious imagination left to the viewer, that is to say, the creator, and that, subliminally, when we leave the cinema, we leave the writer=man rooted in the binomial, and that at all it appears mythologized. When I read the autobiography Memories of the Rose by

Consuelo Uncin, I did not like the subordination and fascination that his wife showed to the writer (“You have a message to give to human beings. Nothing can stop you. I didn’t like it myself”), but I even less liked the need to be the hero of the writer (“I need to be shot, I need to feel clean and calm in this absurd war”). I wonder to what extent these relations and the anachronistic gradations that have been reflected in contemporary cinema are relevant.

It happened in the sky of Buenos Aires on a plane. The pilot shut down the engines to get the bidder's kiss. And the woman, frightened, discouraged, cried out horribly. As they crumbled towards the Río de la Plata, the man told her that he understood that he did not want to kiss her, because she was ugly, and again he managed to impress the woman's heart. “I love you because you’re a little girl and you’re scared,” she said, and with that the woman kissed him. “These are little hands! A little girl's hands at all! Give it to me forever!” he began to retract as he turned the engines on. “I don’t want to be a fool!” the woman replied. “You are so funny! I'm asking you to marry me. I love your hands. I want it to be just for me,” the man ventured, and the woman shamelessly pretended that they knew each other for only a few hours. “See, see how you marry me,” concluded the pilot, and also achieved it in the finish.This real anecdote between

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and Consuelo Uncin has reminded me of two films that I have seen recently by chance, namely Bright star by Jane Campion –remember the movie Piano– and The Last Stop by Michael Hoffman. The first one includes the last days of the writer Leon Tolstoy and reflects his fluctuating relations with his rich wife Sofia –Helen Mirren–; the second one also summarized the last months of the poet John Keats and, okay, maybe his couturier Fanny –Abble Cornish– has more prominence than the poet himself. Both films are beautiful, perhaps the first more social and the second more poetic, but the tempus and, in essence, the narration of both are similar, and I find that, in this tension between the writer and the muse, the winner is the first in the unconscious imagination left to the viewer, that is to say, the creator, and that, subliminally, when we leave the cinema, we leave the writer=man rooted in the binomial, and that at all it appears mythologized. When I read the autobiography Memories of the Rose by

Consuelo Uncin, I did not like the subordination and fascination that his wife showed to the writer (“You have a message to give to human beings. Nothing can stop you. I didn’t like it myself”), but I even less liked the need to be the hero of the writer (“I need to be shot, I need to feel clean and calm in this absurd war”). I wonder to what extent these relations and the anachronistic gradations that have been reflected in contemporary cinema are relevant.

Most read

Using Matomo

#1

Mikel Garcia Idiakez

#2

Iñigo Martinez Peña

#3

Xabier Letona Biteri

#4

Cira Crespo

Newest

2025-04-04

Eneko Imaz Galparsoro

"Rebellion grows in Argentina, a whole people is pushing"

Laura Taffetani works at the Argentine Lawyers Guild (Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1963). He has worked with numerous Mapuches who have suffered government repression in recent years and has been part of the anti-imperialist meetings organized by the organization Liberation in the... [+]

2025-04-04

Xabier Letona Biteri

The Basque Government evacuates Etxarri II Youth Centre in Bilbao

As announced, the Etxarri II youth centre in the Rekalde district of Bilbao has been evacuated with the operation launched by the Basque Government at 9 a.m. In the afternoon there will be a protest demonstration in the neighborhood, starting at 19:00 from the train station of... [+]

2025-04-04

ARGIA

A worker dies falling from a work in Agoitz

The incident took place on Thursday and SOS Navarre was informed that it was about to hit 16:00 hours. The doctor, the ambulance and the Foral are for him, but they have not been able to recover the man and he dies there.

2025-04-04

ARGIA

83 cities have registered for Euskaraldia Hika

It's a novelty this year. In addition to choosing between the roles of voice and ear, citizens will have the opportunity to participate in Euskaraldia Hika. In villages where the Hitano is not used, the use of both toka and noka will be encouraged, and in villages where the... [+]

2025-04-04

Ainhoa Mariezkurrena Etxabe

I'm talking about Interview. With water and sand

Ways to Crush the Earth

I'm talking about Interview. With water and sand

Authors: Telmo Irureta and Mireia Gabilondo.

The actors: Telmo Irureta and Dorleta Urretabizkaia.

Directed by: Assisted by Mireia Gabilondo.

The company is: The temptation.

When: April 2nd.

In which: At the Victoria Eugenia... [+]

2025-04-04

Sustatu

Kneecap film, now with Basque subtitles

Do you know the movie Kneecap? He was selected for the Oscars. It's the story of a trio in Belfast. Kneecap is currently a popular Hip Hop group with a clear pro-language (Gaelic) attitude, the film narrates the vicissitudes of the post-IRA generation; drugs and music, Irish... [+]

2025-04-04

Gorka Peñagarikano Goikoetxea

The Children's Philosophy Podcast will premiere on Sunday: 'Wild Questions', by Iñigo Martínez

In the face of some questions, Iñigo Martínez says that over and over again adults feel like children because “life is full of existential holes”. The professor and philosopher plan to devote the question to "seeking provisional answers". The LUZ media will offer you the... [+]

2025-04-04

Euskal Irratiak

Beñat Molimos: “Herritarren babesari esker du Laborantza Ganbarak iraun hogei urte hauetan”

Euskal Herriko Laborantza Ganberak hogei urte bete ditu. 2005ean sorturik, bataila anitzetatik pasa da Ainiza-Monjoloseko erakundea. Epaiketak, sustengu kanpainak edota Lurramaren sortzea, gorabehera ainitz izan ditu hogei urtez.

2025-04-04

Unai Lomana Uribezubia

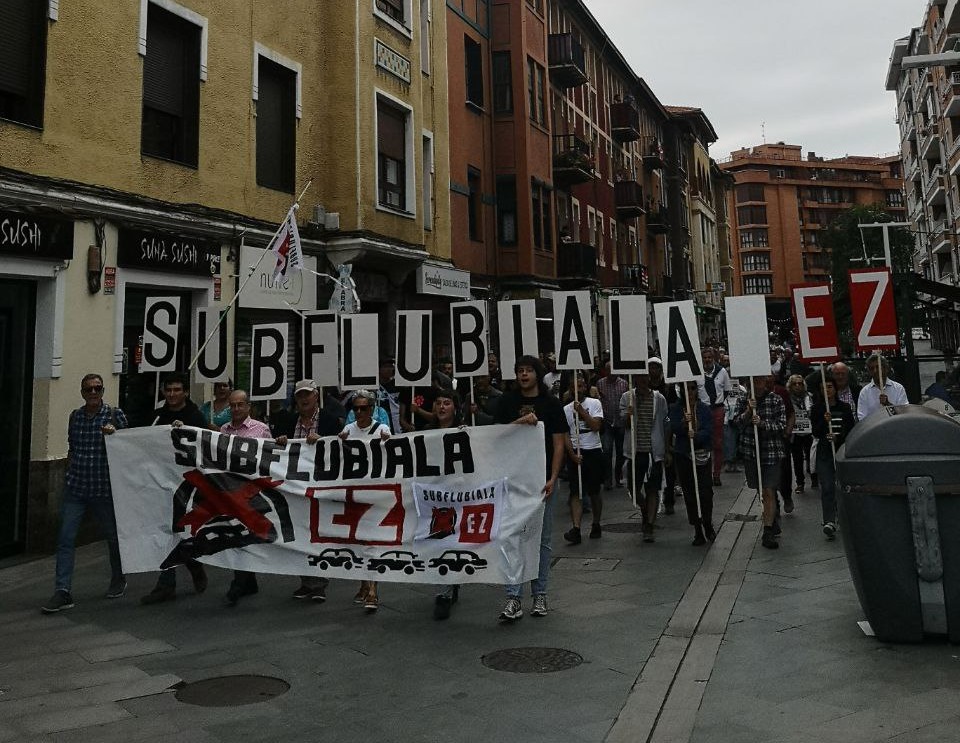

This Friday 'Subfluvial No!' will mobilize against the legalization of explosions for the works of the Ria Tunnel

Organize the human chain Subfluvial No! The platform and the appointment have been made at the Instituto Artaza-Romo at 18:00 today. The Provincial Council of Bizkaia aims to modify the Environmental Impact Statement (EIA) and this is not accepted by the platform.

2025-04-04

Xabier Letona Biteri

High and dangerous levels of pollution have been observed in the surroundings of the Puentes incinerator

These are the results of a study carried out by Toxicowatch, an organization dedicated to the analysis of the level of pollution in Europe. The first studies were carried out before the incinerator was put into operation, after which the samples until 2024 have been analyzed... [+]

2025-04-03

Eneko Imaz Galparsoro

Hungary shows its support for Netanyahu and ceases to be a member of the International Criminal Court

The decision was announced by Hungarian Prime Minister Gergely Gulyas on the same day that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, whose arrest warrant has been issued by the Hague Court, arrived in the country.Israel Katz, Israel’s defense minister, has said the Israeli... [+]

Eguneraketa berriak daude