Orantzaro explains that he refers to a time: ‘at a time when the sun is weaker. Then the ancient Basques made rituals and special pagan parties to reinforce it, especially with the fire. Orantzaro is Christmas, the new sun’. Christianity is based on the festival of the sun or the solstice celebrated by the Basque tribe before Christmas was consolidated: “In our country we have collected the mark of it in the villages, in all the rituals that were made around the fire.”

Surviving uses

They are still habits that survive: “In Sorobarren, for example, a new fire is made on the day of Orantzaro. They leave the old fire, and with the coals of that old man they create the new one. Once made the new ones put a piece of wood or a piece for each family member or relative, according to their name. For the poor another and for God another». It was a pretext for bringing together all family members: “It was a day and a sacred ritual. Michael, the elder master, had been a pastor of Leitzar when he was young and spent the winter there, but that day he returned home walking down the mountain to make a new fire and make a special arrangement.”

Those of Leitza have called Orantzaro eguna as of December 24: ‘a day or a rich time to eat, because in our language it is time to eat with a lot of yeast, bread, food, etc.’ In this sense, Oiartzun explains that many other meanings have been created: “The special trunk that day was burned in the fire was called the trunk of Orantzaro. In other dwellings, instead of burning them, they put in the room a large and singular trunk, which adorned with acebo and other herbs and flowers". Orantzaro was also a magical character: ‘mainly in rural areas. It was a ghost that could commit any barbarity, if the children had not retired to sleep when entering through the fireplace. The ghost that took the axe away from the children of the dwarf Auzmendi…”. In the Sakulu district he was also a terrible man who frightened the children on the day of Orantzaro, with a sheet and a light pumpkin on his head. The children told him great curses and sang the song Orantzaro de Leitza." It was also a gentilla that lost its eye, “if in the Erasote district it launches or gives something on the day of Orantzaro, Orantzaro loses his eye…”.

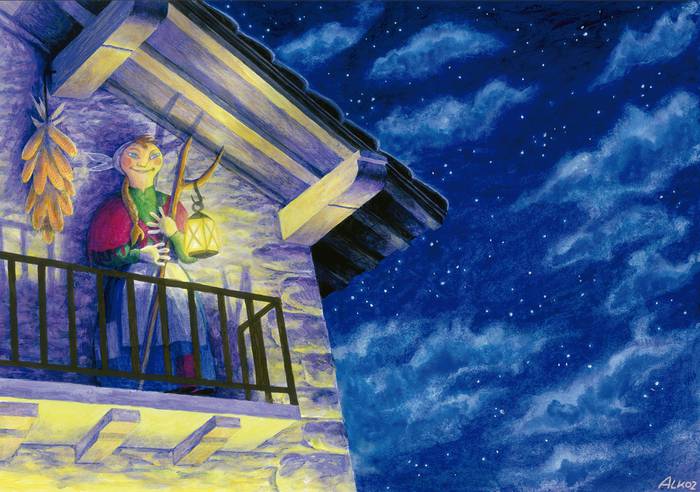

‘They were dolls placed in windows, balconies or fireplaces on 23 December, at will’

Different dolls, all valid

The doll is, however, the most widespread habit today with this word: “The Orantzaros are dolls that were placed in windows, balconies or fireplaces in the village and in the dwellings on the night of 23 December.” He wanted to stress that all the dolls were ‘and they were all scars: the old one hanging from the window, the image of a well-dressed mayor, the mower at the tip of the fireplace, the woman who was sewing on the balcony, the terrible doll with a pumpkin head shaped like a witch…’. Each year a new doll was made: ‘in the form of a boy or a man, but also in many other ways: girl, grandmother, witch and undefined gender’.

Complaint by women

However, over time, this custom of making the doll a la carte changed: "When we in the cultural group have asked about this issue, many women have complained to us with the intention of denouncing what has happened to this issue, or at least to claim the marginalization of the figure of women. Some even referred to the shame of having placed an image of woman: “We knew it, and so did our elders. But now it’s embarrassing that it isn’t,’ we’ve heard it many times.” Inaxi de Aliñe also told them: “That’s how he told us.” The man who wanted it could fix it as he wanted it. But then they began to say no. I didn't need it that way and it's over." The elderly were the only people who received criticism: "Itziar Sagastibeltza also said in the year 2000, in a Christmas program of the Television Basque Country, what was the tradition here. That the time of Oranza could be the same for a woman as for a man. Several friends reproached him for saying that.”

“We would like to know and know what the custom was like. That tradition can be maintained and renewed"

A centuries-old tradition

However, the references of history are there to silence the ignorant: “The oldest reference we have found is that of 1914 and, interestingly, the first Orantzaro was a woman. On December 24, travelers arriving from Donostia-San Sebastian were surprised to see a woman leaning on the balcony of the Garagartza village and who was about to go out in the street. The snow fell, which was very well dressed. It was a doll, ready for the tradition of the day. Maria Luisa de Dendarín told us this at age 92 or at age 92.”

Imagination in dance

The imagination began to dance and the results were often strange: “Asuntzion Lasarte has told us on more than one occasion that in Katalintxone there were some very curious Orantzaros: a man stood in his hand with two plates and, if someone approached, he played chapas, kax-kax. This is a reference of 1.920 years.’

Supplemented by what was available to them

To complete the Orantzaldia they used the items they had at home: ‘they should be nice, elegant and special’. Thus, "to form the body they used sticks and to heal the interior they used straw or walnut. There were also some mannequins in the village. To make the head, they empty the pumpkin, used the heads of the wrists or made them with straw inside a cloth." They also had to dress, “some wore old clothes, but others wore elegant clothes. To adorn the head many used buttons, small fabrics.”

Testimonials

The members of Altzadi Kultur Elkartea have worked in collecting testimonies so that this custom remains in the collective memory and is accessible in the future: ‘We are now producing a video to show the people what we have received through the testimonies and have it well collected’. Its objective is clear: “We would like people here to know and know what the custom of the place was like. And by the way, anyone who wants can maintain it and renew their tradition."