Living in a rich or poor neighborhood directly influences the political participation of citizens. In fact, according to several researchers, the degree of electoral abstention in low-income population centers is increasing both in Donostia-San Sebastián and in the rest of the world. To make this reality visible, the Montera34 laboratory has drawn up a map of the neighborhood by neighborhood of the abstention, after analyzing the data obtained in the last Basque regional elections.

Through this map, the researcher of the University of Deusto, Braulio Gómez, has made visible the points defined as “black holes in democracy” (areas with a degree of abstention greater than 50%). These include the neighbourhoods of Otxarkoaga (Bilbao) and Abetxuko (Vitoria-Gasteiz).

In order to clarify the reality of these black holes, the Zubiak Eraikiz platform has organized a conference tour throughout the community, together with the researcher Gomez and Pablo Rey de Montera34. The leader of the platform, Sabin Zubiri, has clarified that there are no extreme cases such as Otxarkoaga or Abetxuko in Donostia-San Sebastián, but there is a clear correlation between abstention and income in the city’s neighborhoods.

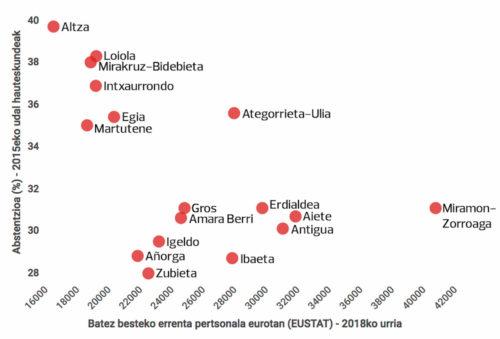

According to October 2018 data from Eustat, the residents with the lowest personal incomes of Donostia-San Sebastian are the inhabitants of Altza (16,575 euros), while the most rented residents reside in Miramón and Zorroaga (40,850 euros). Reviewing data from the 2015 municipal elections, a difference is added to the economic difference between the two areas: In Altza the rate of abstention was 40% and in MIRAMON and Zorroaga 31.4%.

As shown in the attached graph, the highest levels of abstention in these elections were concentrated in the neighborhoods with the lowest average personal income, especially in Altza, Loiola and Bidebieta. Likewise, the neighborhoods with higher personal income showed lower levels of abstention. Zubiri explained that in the municipal elections of 2011 and in the municipal elections of 2016 the same trend was repeated, confirming the achievement between social classes and political participation: “The data show that this abstention is structural.”

In the elections last Sunday, the levels of neighborhood abstention per neighborhood underwent significant changes, according to the participation data collected by the PNV of Donostia-San Sebastián. However, Zubiri pointed out that the Spanish Ministry of the Interior has not yet published any official information about the neighborhoods and has warned that it is "dangerous" to draw conclusions without that information.

Social class gap, unbalanced representation

This link between the social class and political participation calls into question the proper functioning of the democratic system. The fact is that, although people from the most disadvantaged social classes can also vote, Zubiri has stated that this right to participate in the elections is conditional: “Their socio-economic situation reduces the likelihood of voting, increasing abstention and reducing their political representation.”

Platform member Zubiak Eraikiz explained that there are many theories about the causes behind this phenomenon and that it is difficult to determine a specific cause. However, it seems clear that having something in the refrigerator every day or being able to pay the rent is more difficult for those who are primarily concerned to receive political information and reflect on collective problems. According to Zubiri, “these people feel the politics quite far away, because they do not respond directly to their daily concerns, and that feeling becomes indifferent on election day.”

In the construction of a fair democratic system, overcoming this imbalance among the electors is seen as a step forward. Unfortunately, Zubiri, aware of the experiences gained at the international level, believes that there are no magic formulas to change the situation. However, the member of Eraikiz said that there are measures that can help bridge the gap in which one lives.

For example, it has been shown that compulsory voting is an effective measure to balance participation in different countries. It is used in various parts of Latin America, as well as in Belgium, Luxembourg and Australia. In recent years, the turnout rate has tended to be close to 90 per cent on election days.

This system operates simply: the citizen is obliged to vote and, if he fails to do his duty, he receives a small fine. Due to the greater interest of citizens with lower incomes for not being fined, their degree of abstention is reduced, balancing the overall participation.

According to Zubiri, “from our point of view, switching to the compulsory voting system would be difficult, but there are other measures that we can implement in our country.” The platform points out that, taking as an example the social and economic objectives that governments set at the beginning of each term, leaders should set specific policy objectives: “Feasible measures must be taken to promote the political socialisation of social classes in situations of exclusion. For example, to promote political information and to help strengthen social relations among citizens.”

In addition, Zubiri has indicated that it is for the parties to cut off the vicious circle created in the areas of abstention: “If there is little voting in a neighborhood, the candidates are not interested in their citizens, who abstain again in the next elections.” Indeed, the expert has stressed that parties follow the logic of the market: “In some areas with a high degree of abstention, there has never been any political act.” He has therefore considered that if politics is to be brought closer to a part of society that is far from the political debate, it is necessary to move political action to those spaces.

Change of trend

Official data on resident participation in last Sunday’s elections in Spain have not yet been published and only figures for political parties’ participation have been published for the time being. In the absence of official data, the percentages received can only be considered significantly. However, this non-definitive information points to a change in the tendency of participation in the neighborhoods of the city.

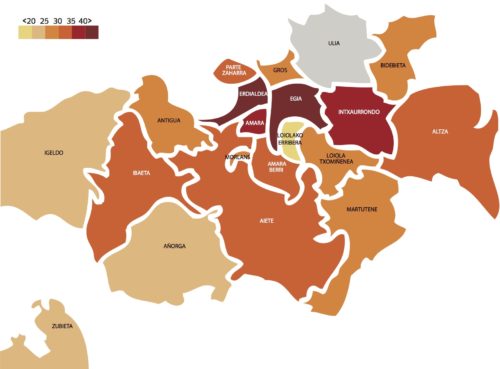

Neighborhood to neighborhood participation in the April 28 elections. (Source: Donostia-San Sebastián)

As can be seen from the map drawn up by the PNV, the levels of abstention in Egia and Centro have risen considerably, while those in Altza and Bidebieta have fallen considerably. Behind these changes there may be several reasons. On the one hand, the growth in participation has reflected the mobilization of a part of society that had not so far voted. In particular, the city’s participation in the municipal elections this Sunday increased by eight points compared to the municipal elections of 2015 and by nearly seven points compared to the general elections of 2016.

On the other hand, as Zubiri points out, last Sunday the Spanish right suffered a sharp setback in the city and the Abertzale left had to face a campaign in favour of abstention. The member of Eraikiz concluded that these events have redrawn the trend of resident participation in the neighborhood, but has insisted that the information received is “quite surprising”, so we have to wait for the official data to be collected.

Other factors

In addition to the average income, Zubiri has mentioned other factors that mark the general social class of a neighborhood, such as the cultural level of its inhabitants and the power of social relations among them. In fact, when these are high, the expert states that the political participation of the inhabitants of a given area tends to increase.

The case of Añorga, Igeldo and Zubieta is quite significant in this regard. In the municipal elections of 2015 and last Sunday, the three have shown the lowest levels of abstention, and although their inhabitants have similar incomes, Zubiri explained that he has another reason to have similarities with the data obtained in these spaces: “In small towns and in some neighbourhoods with great social relations, neighbors spread to each other the tendency to vote, because in a strong community with political conscience the electoral environment extends a lot.”

There are other factors that determine the degree of participation, beyond the social class. With regard to age, for example, Zubiri pointed out that young people vote less than adults and that the accessibility of polling stations can also influence a whole constituency: “The fact that a goiter is on a hill can make many older people not vote.” By analyzing the 2015 election graph, it can be concluded that this last factor has influenced the degree of abstention of Ulía and Ategorrieta.

Thus, on the eve of the municipal elections on 26 May, the objective of achieving a more representative and fair democratic system requires an analysis of the data collected so far in the votes and concrete action to be taken on the basis of them.

This article has been posted by the HI-s of Irutxulo and we have brought it with the CC by license