We are at the gates of carnivals and carnivals. Like every year, immersed in this seasonal era that remains physically cyclical. Although it's still winter, it's when we start to smell its end.

Debates and decisions on this year's costume begin in the whatsapp groups of the crews. “What are we doing this year?” It doesn't matter if you're going to play in the village or in the neighboring village, or in the capital. The important thing, choose the theme. Then the futures.

There are people who each year take the path of comfort (the classics (clowns, hippie, bakero…), reusing the costume of a previous year, or every year they seek originality (the characters of the fashion series, the costumes that refer to the famous news of the year,…). And then, apart from that, which is perfectly compatible with all of the above, of course, there are also people who go on a hike to some corner of Euskal Herria, who will see their carnivals. Traditional, authentic. As if one thing (the Saturday juerga disguised as hippie) had nothing to do with the other (the “traditional” carnivals).

As at present, the old society had to face many risks to ensure its survival. Their biggest risk, at least one of the biggest, was the eternity of winter. At least for homo sapiens, who after 10,000 years of agrarian revolution chose to live together with the land and its sowing. If winter continues, their survival was in danger. They needed the soil to be reproductive, so that it could be recultivated. That is why every year they faced a cyclical struggle: the struggle between winter and spring, between life and death. Collision between chaos and order.

At one time, the bear was still very present, when it came down from the mountain to the village, it announced the end of the winter when it crashed out of its winter. The population was aware that the end of the winter was close. Then rites and scams continued to exist in many villages to move away from winter and attract spring: it is time for carnival.

It is known that these auctions and rites have great similarities in most places, in many parts of Europe on the slopes, but as a garment. The problem to be tackled was the same and common there and here. And in Bakio, of course, at one time it was also like this. The carnival was also celebrated for many years. Own, own.

Anarruak and Anarru eguna in Bakio

When the Carnival came, in Bakio the anarros went out to the street, to the roads of the dwellings and the neighborhoods, with darkness. Carnival day in Bakio was the mood day, the word that today is about to lose (or has been). Fortunately, many older pacifists still remember.

Our chiquitos, costumes, kokomarros or stripes are therefore ambarros. On the one hand, it is linked to the interviews carried out now and before the elderly in Bakio, which was called the pineapple, to the mask itself (used “anarrua jantzi”, “rip off”,…). And it also called pineapple the disguised person, the disguised person. The word Anarrutu is also gathered in the testimonies to disguise (bichear).

Anarru Day, in principle, was Carnival Tuesday, although in some testimonies it was stated that “sometimes it was on Sunday, because it was easier to know” (Tuesday was working).

Father Juan Ormaza, 84, whom we have interviewed, also came out as a child dressed in pineapple, “at age 15 or more.” Always with the concealed face (“even if the pumpkin is emptied and gets stuck in the head once”), with the intention of frightening anyone in front.

“I have also put myself in pineapple, in pineapple. 15 years or more Before, there is no light. As for the days of the animals in the mansion, I went home with every year. Dress with zucchini or in any way to investigate jentie. To be clear, not to know who is called, the arpixe lid and...”. Juan Ormaza Rentería (1940) / 2020.02.23

According to María Angeles Zabala, when she was a girl (this year she will be 87 years old) “she came a year to her father dressed in pineapple. We've never known who he was. (…/…). He brought his face covered and dressed in old clothes.”

“Anarrue is for me a person (in Spanish) with the imindxe costume. “It comes dressed in pineapple,” we said the hours. And the aitxeñe weave every year, one, pineapple dress. He doesn't know who he was. Iguel aitxe does have us not. We played the tapeta Erpeidxe, and well, we dressed the old soups and so on.” Maria Angeles “Txikitina” Zabala Larrazabal (1937) / 2024.01.12

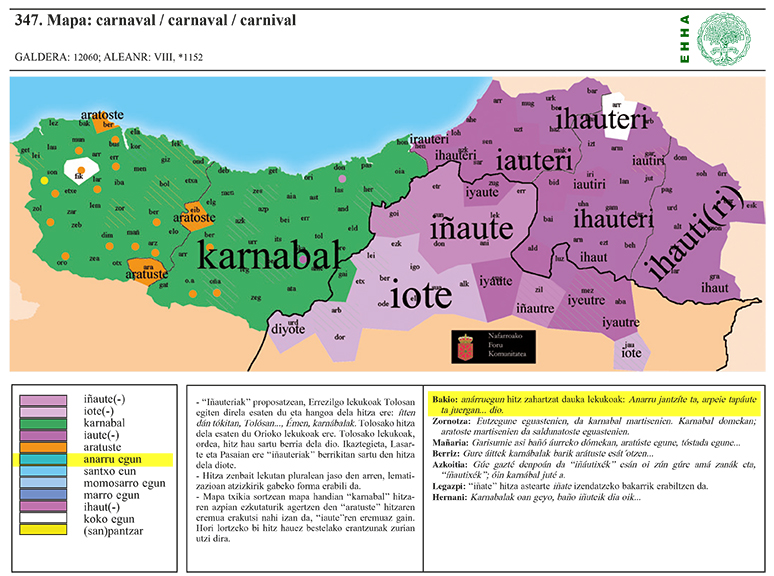

The written bibliography also includes the date of the anarru and anarru of Bakio. It is included, on the one hand, in the “Atlas of the Popular Language of the Basque Country” published by Euskaltzaindia. The map of the word Karnabal shows “anarru egun”, and the legend says that “Bakio: anárruegun is considered an old word: Anarru sees, arpeie tapaute ta juergan…” he says.

“Jentilbaratz. In the issue “El folclore infantil en Euskal Herria” of the magazine “Cuadernos de Folklore” the shield is also mentioned. What's more, J.E. Larrinaga also collects a motto compiled in 1986 in Bakio, a Txomin Uriarte of the Urkitza de Bakio farmhouse:

“Anarru prakagorri

Carnival.

Roasted lots of commas

Eta ez daukagar”.

So we have the basis of our natural carnival, the day of Anarru, and the character of this one, to reclaim the pineapple and structure our own popular carnival. And that is what the people of Bakio, led by the Itxas-Alde Dances Group, will do this year: stop reproducing the carnivals of other corners (on the one hand, those that have helped us to get into the operation of carnivals and to understand the system), and start by us.

Pineapple and other characters

As I say, the anarrua will be the protagonist of the carnivals of Bakio. Let the face inevitably be covered and, with the excuse of the copite that is collected in Bakio, put red frac. That will be our trait: the red fracas.

It is also known the relationship of red color with carnivals and their incantations and sides. Urbeltz himself mentions in his book "Basque dance: approach to symbols" that red is the color of hunger and pests. Because if winter was one of the greatest dangers of society in the past, pests (and of course bugs) were no less. The fight against winter was also a fight against the plague in which the bugs in one way or another were enemies (it has been written long and laid that is the same disgusting word and bug, the two sides of the same coin. Dress up, bichear, because it becomes a bug.) Red is the color of hunger because when hunger is big it is “red hunger,” as if winter is hard it is “red winter.” That’s why “Petiri-Santz” (embodiment of hunger, misery or sinister) also wears red frac.

Anarrua will not be the only character of Anarru's day in Bakio. Protagonist yes (he gives name to the day), but not the only one. Returning to the issue of brothers, we have met other characters or beings: idols. According to the interviewed population, idols are night gowns, blowbeds. Those who take the form of beasts or animals and sometimes represent fires through their mouths. They are scary beings. But it's not just a being that's picked up in Bakio. Stories and stories from other towns in the area are also collected (Bermeo, Mungialdea,...). Joxe Miel Barandiaran also did so in “Complete Works”, accusing him of donkey, pork or black acer. Always in the form of an animal.

“Umieri, you say it to you mom, you, beware! Don't go there without the idols having them! What ten are idols? Explosion. Similar to animalidxes, ghost… anything!” Juan Ormaza Rentería (1940) / 2020.02.23

Thus, to join the day of Anarru (and to complete or enrich it), a being that takes the form of an animal dressed in horns and skins (as in so many other carnivals): the idol. These are also ready to go to the streets of Bakio!

And, of course, the day of Anarru in Bakio will not miss other essential elements and characters in many carnivals, such as the bear announcing the end of the winter (and its fermenter), the vine and the corncoves (which are covered with grape leaves and corn leaves) (Bakio also maintains a close relationship with the maize, which in his town opened the path of the bonfire and the ravines).

Thief Joseostu

It is a recurring rite in many carnivals, the capture, judgment, punishment and death of the character responsible for all the evils of the people (being shooting, smoking, throwing and drowning the river…). The Miel Otxin de Lantz or the Markitos de Zalduondo are well known, but there are many criminals or thieves who incarnate in a doll that is tried and sentenced to death.

Iñaki Martiartu is a relentless town researcher who has been exploring local archives and libraries for years. We must not forget that he is also a tireless dancer. In fact, for many years he was a dance teacher of the Bakio Itxas-Alde Group of Dances (and when the group became official as an association, in 1986 he was also its first president). He is still a person who is always close to the group. He has been researching Bakio’s toponymy in depth for more than two decades, and at the same time collecting it, all the information he has received about Bakio is inquantifiable. We have also talked to him about Anarru’s day and its constitution (his knowledge has been indispensable), and through him we have met a Bakio thief who was known in his day: Joseph de Ormaza.

Joseph de Ormaza was a Bakiotarra who lived in the mid-18th century, a criminal who dedicated himself to stealing and sowing fear in Bakio and nearby villages. One day he was arrested and imprisoned with 10 years of military conviction. But in 1755 he fled prison. Shortly afterwards he was captured again and then he was sentenced to death. He was shot on 25 October 1756 at 22. The robber we have appointed as a joint will be responsible for all the evils of the people and with his judgment, punishment and smoking we will end the day of Anarru. Around them we will dance the zortziko of Anarruen, with the music we have created for the day.

Txakoli and zahagi-dantza

If we continue to delve into the characteristics of Bakio, there is something that is ours, which makes Bakio known beyond its limits: the txakoli. As the famous bilbainada always recalls: ‘Sardines those of Santurce, Bermeo, txakoli gorri de Bakio and tomatoes of Deusto’.

In the past, most of the villages produced the txakoli in Bakio, but the different pests of the 19th and early 20th centuries (phylloxeras, pastors,...) considerably reduced the vineyards of Bakio, even reaching almost to disappear. For example, in the 1920s, Barturen de Bakio was about 16,000 liters. Ten years later, they barely made a few liters to drink inside the family. Fortunately, nowadays the exploitation of txakoli is revitalized in the municipality: there are three wineries dedicated to the professional production of txakoli, and there are still some farms that do it for their own consumption.

With all this, we have inevitably joined the dances of cascabels dancing in different carnavales.La presence of wine, boats or zahates is common in carnivals and mascaradas.Por one side, because bugs (and therefore costumes) like wine and are an essential element to attract them (frequently used as retribution). In addition, as with other inflated characters of the carnivals to which Urbeltz alludes (Ziripot, Zaku-zaharrak…), the wine stalls would symbolize the larvae of the insects, the origin of the bugs, the origin of the pests… And so they hit and hit until they fall dead to the ground. That's why we're going to dance on Bakio to keep the pest away from the claws.

In the Itxas-Alde dance group, the zahagi-dantza that has been dancing since the 1970s is from Arano (do not ask why). That's what we've done over the last 50 years. So, what we are going to do on Anarru's day, we are going to follow that way of dancing the dandruff, which, of course, we are going to do with the music and variants that we created for that day (plus ours).

Dissemination and social inclusion

In order to publicize this research and recovery work to the people, and to be part of this same town, in collaboration with the City Hall of Bakio and Maule Productions, in recent weeks various initiatives have been developed: on January 19 the conference Itxas-Alde dantza taleak was held in the Txakolingunea; criteria have been recorded for the children and youth population of Bakio productions. This year the Itxas-Alde dance group will lead the day of Anarru, for which the first seed will be planted. But in the coming years, the participation of other associations, citizens and entrepreneurs will be promoted so that this seed can take root and flourish in a deep and stable way, so that the people can take over the day of Anarru.

On February 17, 2024, after decades, the anarrue will return to the streets of Bakio: Starting at the fronton of the Tabernalde, there will be a tour of the village’s regatta, next to the shore of the water in which the insects or bugs live. After a stop at the Town Hall Square to perform the Zahagi-Dantza, in the Plaza de Arezabal the day of Anarru will be closed with the roast of Joseostu and the zortziko of the anarrue that will dance around him.

On this occasion we have managed to reconnect the thread of the heritage transfer before it is broken without turning back. We have the ability to keep this new knot almost tied for many years, and we are right with the way to keep this word and tradition alive that we have had about to forget.

Sources:

(1) Talks with the researcher of Bakio Iñaki Prieto Martiartu and the information and testimonies he has received for many years. Includes the interview with Mari Karmen Azkorra and Modesto Barturen (2005).

(2) Interviews with Juan Ormaza Renteria and Mari Angeles Zabala Larrazabal Txikitina (2020, 2024).

(3) Atlas of the Basque People's Language (EHHA). Subject: Annual holidays. Map 347, 158. P. 159

(4) Dueñas, Emilio Xabier, Larrinaga, Josu Erramun (2011). Jentilbaratz. Folklore Notebooks. Children's folklore in the Basque Country. Teaching materials. (R.J. Interview by Larrinaga to Txomin Uriarte Intxausti (1986).

(5) Dueñas, Emilio Xabier (1999). The Carnival tradition in Bizkaia Euskonews (20). Num),

(6) Urbeltz, D.O. (2001). Basque dance (approach to symbols).